The New Artificial Intelligence

Artificial Intelligence has been around for decades, but is the hottest area of technology today because of vast improvements in computing power and data availability. For business, AI offers the potential to greatly improve operational efficiencies, predict consumer preferences and reduce human error, through self-teaching algorithms that can transform business models with unprecedented speed and certainty.

The promise of AI has led to a global surge in investment and a war for scarce talent that threatens to tilt the playing field in favour of a few nations and companies that have the money, datasets and computing power to win at scale. The Analysis Group estimates the global economic impact of AI over the next decade could be worth as much as US$3 trillion.

For Canada, once a leader in the field, the surge in AI has presented a national challenge. The Canadian government recently committed $125 million to a national AI initiative; Quebec added $100 million and Ontario committed another $50 million, largely to retain academic talent in the face of aggressive hiring by Google and Microsoft, among others. Despite these investments, only a fraction of Canadian companies have announced AI programs and the Canadian AI start-up space remains nascent. If Canada is going to remain competitive in the age of artificial intelligence, a more collective ambition will be needed.

[hr]

AI, Defined

The most common approach to artificial intelligence is known as machine learning, a general term used for teaching computers to do things for which they are not explicitly programmed. One way to understand machine learning is as a very advanced form of pattern recognition, and AI researchers seek to teach computers to make inferences and predictions from those patterns.

One important subset of machine learning is called deep learning, where researchers build complex algorithms designed to mimic the reasoning process of the human brain. These so-called neural networks connect a huge number of small, simple processing units into a much larger whole. Take the common example of a cat picture. While no individual artificial neuron can understand what a cat looks like, a neural network can assemble the pieces and see the bigger picture.

Another growing branch of AI is reinforcement learning, an advanced form of trial-and-error reasoning that would be familiar to anyone who’s ever played the board game Battleship. These AI algorithms learn behaviour based on feedback from the environment, thanks to designers who build in rewards for proper actions. Think Pavlov’s dog—with a digital bell.

[hr]

An Academic Head Start

Canada had an early lead thanks to three noted researchers: Geoffrey Hinton, from the University of Toronto; Richard Sutton, from the University of Alberta, and Yoshua Bengio, from the Université de Montréal. This trio has been able to draw the leading talent from around the world to Canada, researchers who are now training post-graduates who will in turn be teaching the next generation of AI talent.

| Montréal | Toronto | Edmonton | |

| Basic researchers | 11 | 6 | 11 |

| Applied AI researchers | 10 | 3 | 8 |

| AI students | 120 | 116 | 75 |

| Estimated Total | 140 | 140 | 107 |

To help retain and nurture academic talent, the federal government, Ontario and 30 corporate backers this year created the Vector Institute, a new AI research facility in Toronto that is seeded with $180 million over 10 years. The Montreal Institute for Learning Algorithms and the Alberta Machine Intelligence Institute follow similar models. But the research resources in other counties, especially the United States, tower over Canada’s. Former students and colleagues of Canada’s three AI leaders now lead AI divisions at Apple, OpenAI, Facebook and Google.

[hr]

The Emergence of AI Superpowers

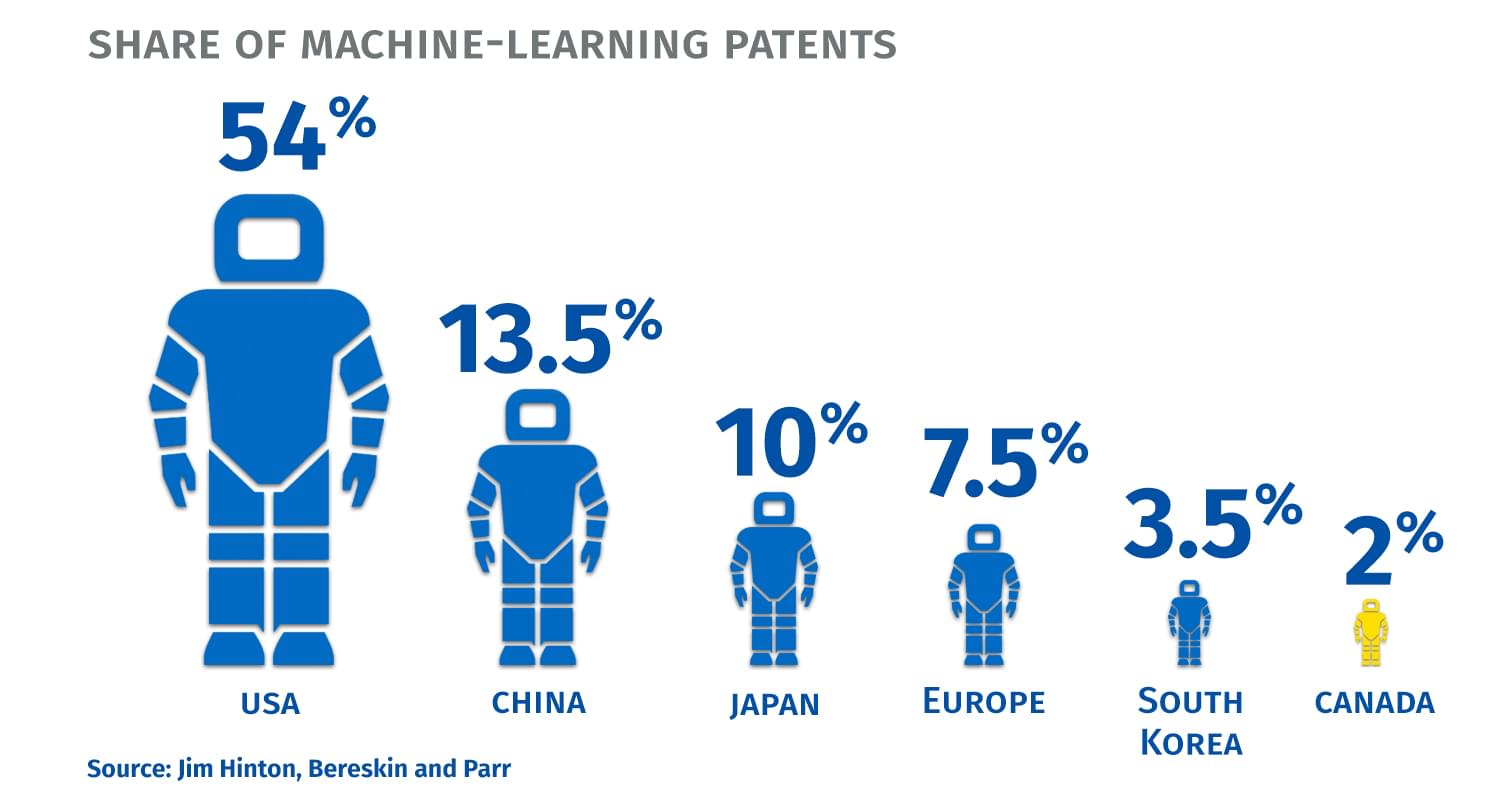

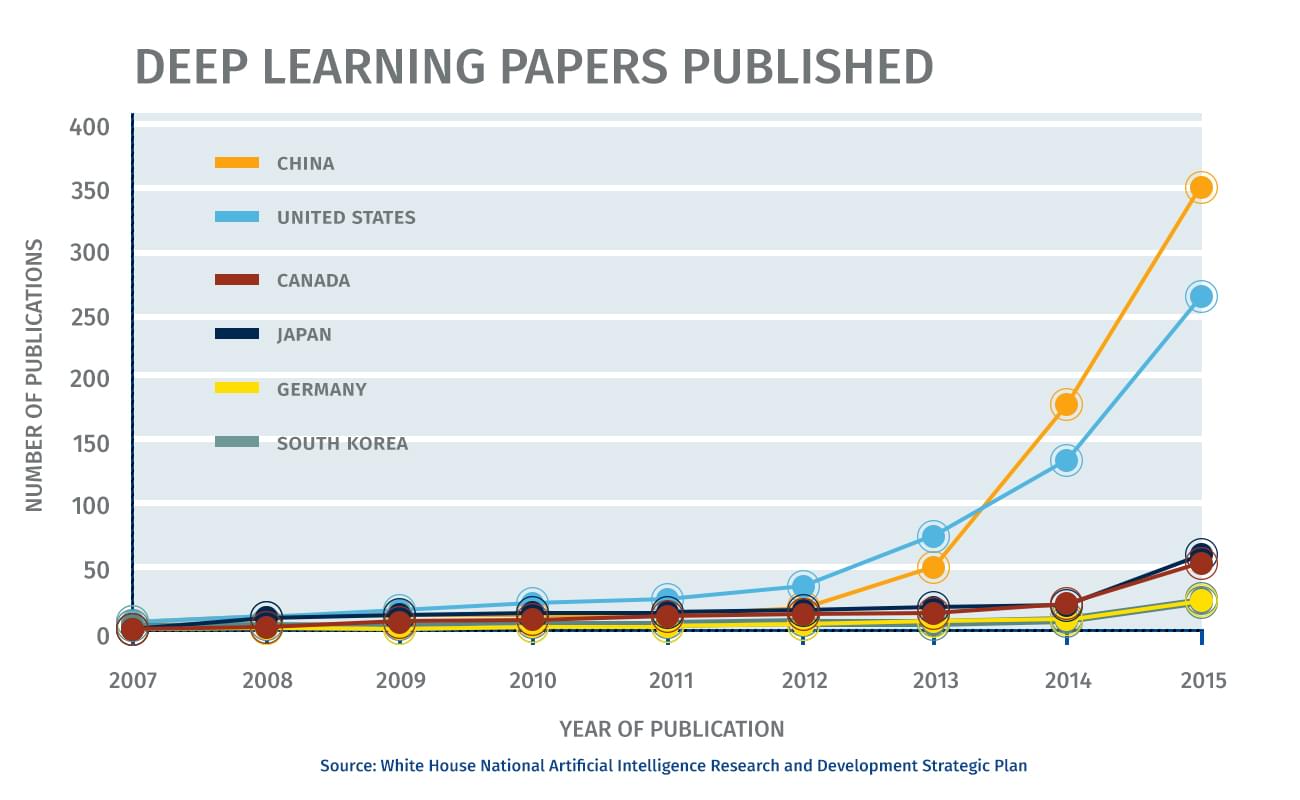

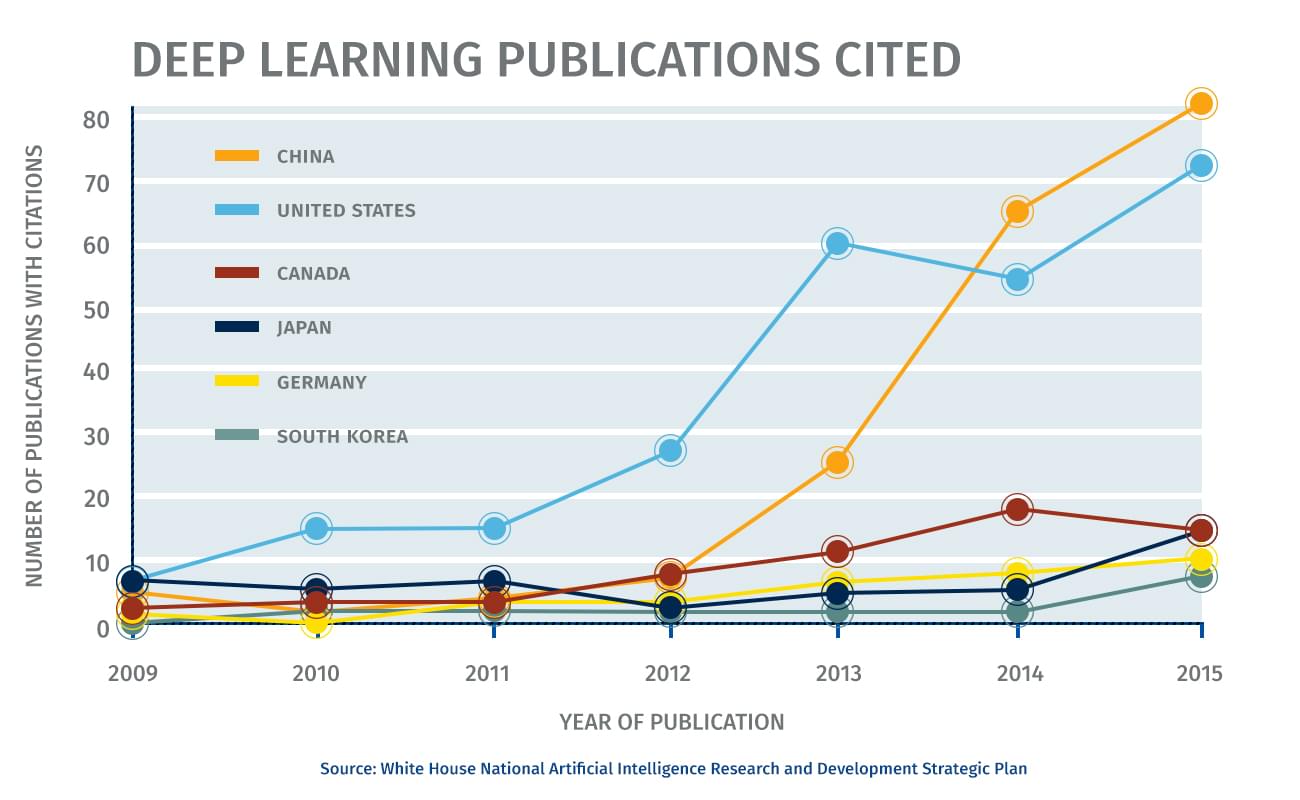

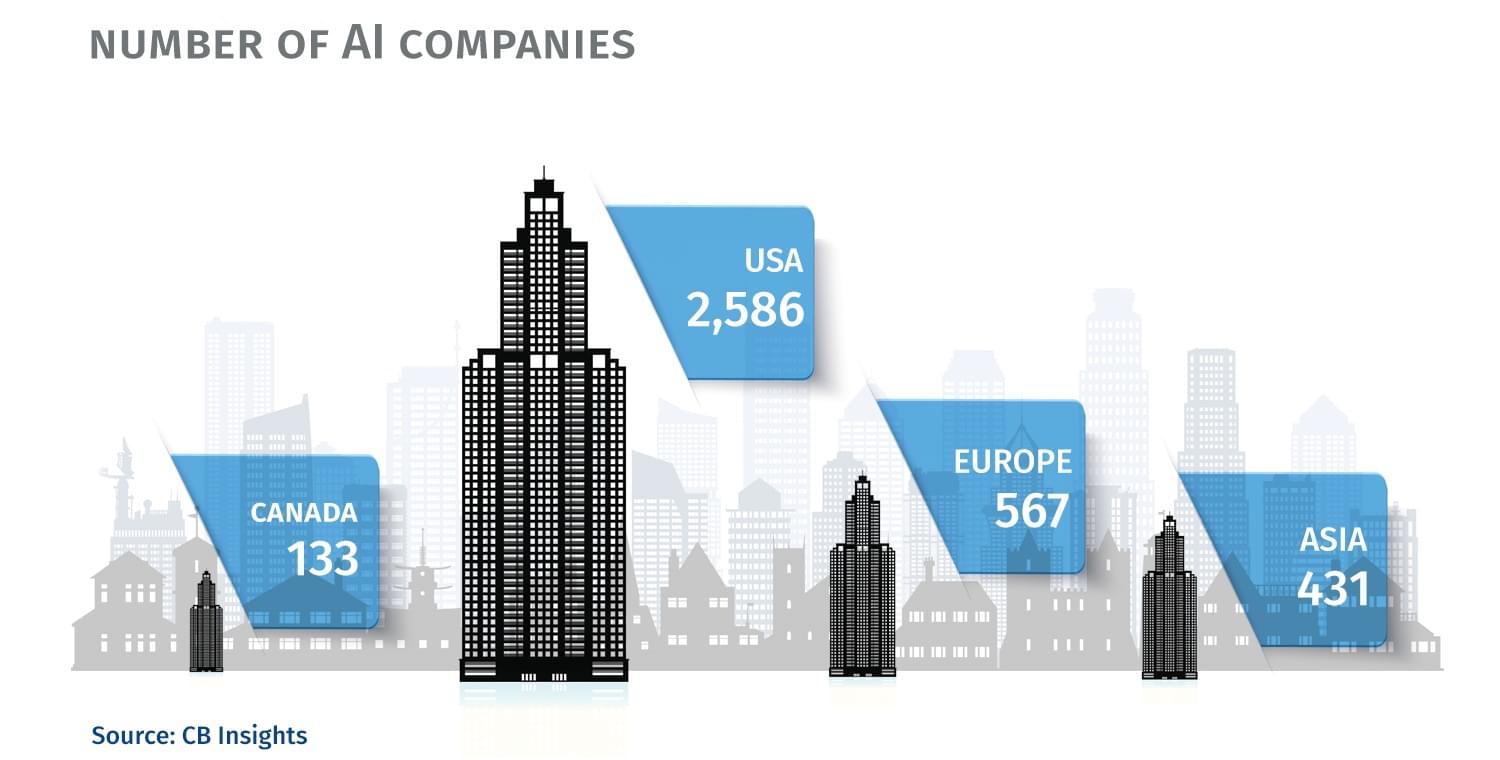

The concentration of AI research has grown sharply since 2012, with the United States and China emerging as AI superpowers.

[hr]

The Start-Up Challenge

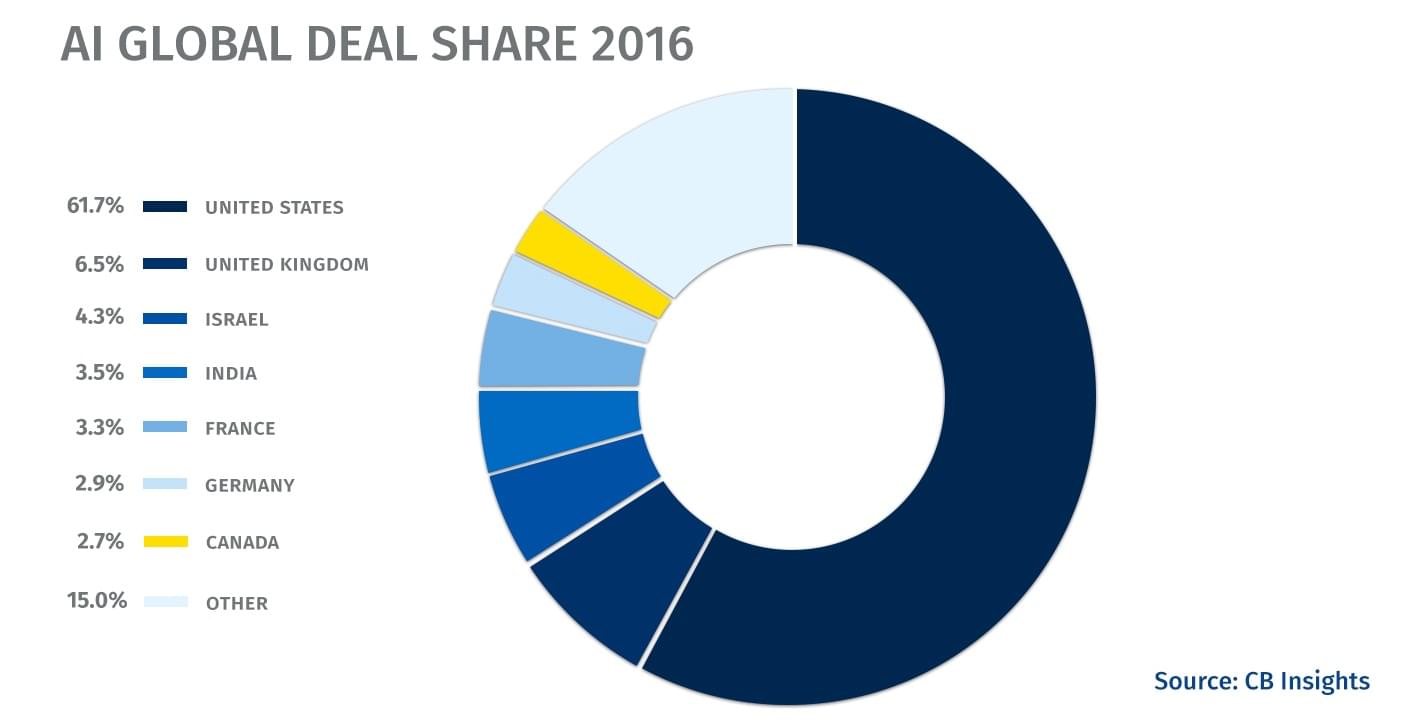

- Around the world, 650 AI start-ups raised US$5 billion in 2016.[1]

- The number of AI deals (funding rounds and exits) has increased more than fivefold since 2012

- Canada accounted for 18 of the 658 AI acquisitions in 2015[2]

- No Canadian company ranks in the top acquirers for AI startups

[hr]

The Corporate Challenge

American tech companies have put millions into Canadian AI. Microsoft pledged to invest $7 million in AI research in Montreal as part of its January 2017 purchase of machine language start-up Maluuba, while Google donated $4.5 million to MILA in 2016 and has opened labs in Montreal and Toronto. In May, Uber hired University of Toronto professor Raquel Urtasun to run a new Toronto AI lab focusing on driverless car technology.

Canadian companies have also invested in AI. NextAI, a partnership between RBC, Magna, BDC Capital and Scotiabank, was launched in 2016, with $5 million in initial funding to draw entrepreneurs to Canada to work on AI challenges. More than 20 Canadian companies have committed to funding the Vector Institute. Of the top 60 companies on the TSX, 22 have expressed interest in AI and 13 have publicly announced investments in AI. (See Appendix).

Between the federal and provincial governments, academic networks and partnerships including the Vector Institute and MILA, and commitments from private corporations, nearly $500 million has been committed to developing Canada’s artificial intelligence ecosystem over the past 18 months.

[hr]

Making Canada AI-Ready – 10 Ways for Government, Business and Academia to Build on Canada’s Success.

1. Create an AI Council to Guide Policy:

A private sector-led council could advise government on AI opportunities and challenges, and help track and benchmark Canada’s adoption of AI relative to global competitors.

2. Expand the AI Talent Pool:

Set an ambitious national target for both graduation levels in AI and related fields, and immigration levels for global AI talent.

3. Make the Workforce AI-Ready:

Equip students with AI-complementary skills, including work-integrated learning to ensure broad student exposure. This should include a focus on girls to ensure more gender balance in AI-related fields, including design, interface and impact.

4. Promote AI Across Business Sectors:

With business groups (Business Council of Canada, chambers of commerce), diffuse understanding of AI across organizations and encourage its adoption by all key sectors to build Canadian competitiveness.

5. Focus Research Funding on Commercial Innovation:

Ensure publicly-funded AI research focuses on commercial application— and require government funding agencies to better coordinate AI investments.

6. Develop an AI-Focused IP Strategy:

Modernize the IP regime to support the monetization and commercial scale-up of ideas in Canada, and to guard against activities (e.g. patent trolling) that stymie Canadian commercial innovation.

7. Leverage Our Data:

Establish a national data strategy, including a possible data bank for Canadian-owned companies and entrepreneurs to help them build scale in key areas.

8. Create a National Challenge:

Pool government and private resources, including data, to help Canadian firms, entrepreneurs and researchers use AI to solve grand challenges such as carbon emissions and hospital wait times.

9. Pursue an AI Trade and Investment Agenda:

Create a subject-expert AI representative in the federal government to work with multinational companies and investors. Apply an AI lens to trade negotiations. Review investment policies to consider the interests of Canadian firms.

10. Position Canada as a Global Leader in Advancing AI for Good:

Play a constructive role, through the G20 and multilateral organizations, to convene and build global awareness about the social, economic and cultural consequences of AI.

[hr]

Appendix

Public AI interest and investment, TSX60 companies [5]

| AI interest | AI investment |

|---|---|

| 1. Bank of Montreal | 1. Bank of Montreal |

| 2. Bank of Nova Scotia | 2. Bank of Nova Scotia |

| 3. Barrick Gold Corporation | 3. BlackBerry Limited |

| 4. BCE Inc. | 4. George Weston Limited |

| 5. BlackBerry Limited | 5. Loblaw Companies Limited |

| 6. Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce | 6. Magna International Inc. |

| 7. CGI Group Inc. | 7. Manulife Financial Corporation |

| 8. George Weston Limited | 8. Power Corporation of Canada |

| 9. Goldcorp Inc. | 9. Royal Bank of Canada |

| 10. Loblaw Companies Limited | 10. Sun Life Financial Inc. |

| 11. Magna International Inc. | 11. Telus Corporation |

| 12. Manulife Financial Corporation | 12. Thomson Reuters Corporation |

| 13. National Bank of Canada | 13. Toronto-Dominion Bank |

| 14. Power Corporation of Canada | |

| 15. Rogers Communications Inc. | |

| 16. Royal Bank of Canada | |

| 17. Sun Life Financial Inc. | |

| 18. Suncor Energy Inc. | |

| 19. Teck Resources Limited | |

| 20. Telus Corporation | |

| 21. Thomson Reuters Corporation | |

| 22. Toronto-Dominion Bank | |

[1] The 2016 AI Recap: Startups See Record High In Deals And Funding. (CB Insights, Jan. 2017.)

[2] The 2016 AI Recap: Startups See Record High In Deals And Funding. (CB Insights, Jan. 2017.)

[3] The Geman Artificial Intelligence Landscape. Asgard.VC, February 2017.

[4] Worldwide Semiannual Cognitive/Artificial Intelligence Systems Spending Guide. (IDC, October 2016.)

[5] Factiva press search

As Senior Vice President, Office of the CEO at RBC, John Stackhouse is responsible for interpreting trends for the executive leadership team and Board of Directors with insights on how these are affecting RBC, its clients and society at large. Prior to this, John was editor-in-chief of The Globe and Mail (2009-14), editor of Report on Business, the newspaper’s national editor, foreign editor and its foreign correspondent based in New Delhi, India (1992-99).

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates. This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward- looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social- impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.