The Discovery

Canadian farmers manage one of the world’s largest inventories of agricultural land.

Canada’s vast area of cultivated agricultural land is the 12th largest globally.

This soil could be a powerful “carbon sink”.

Soil has the potential to store or “sequester” carbon, pulling it out of the atmosphere where it contributes to climate change. Canada’s agricultural land could sequester between 35MT and 38MT of annual GHG emissions—cutting about 25% of potential 2050 emissions, according to our estimates.

By using sustainable practices, farmers can unlock this potential, earn money and protect water, land and air.

Through practices such as cover cropping, reduced tillage and nutrient management, farmers not only increase soil carbon, they also improve water and air quality and preserve biodiversity.

The challenge: soil sequestration on Canadian cropland has fallen by 58%.

Degradation from heavy tillage and practices like mono-cropping (where a single crop is grown year after year on the same land), have halved the amount of carbon stored annually in agricultural soil over the last two decades.

And major financial barriers are deterring farmers from adopting sustainable practices.

Sustainable farming eventually enhances yields. But upfront costs (including for new equipment) and the potential for initial yield loss can pose significant obstacles. This is particularly true for farmers operating on slim margins.

To accelerate adoption of sustainable farming, we’ll need more money.

Financial incentives can boost farm income and assist producers with the costs associated with the transition. Storing 38MT of carbon in soil per year will require incentives of up to $4 billion annually. To secure those funds, we’ll need to find the right financial instruments and funding sources.

Insetting and government funding are currently the best mechanisms to inject this capital.

Carbon offsets will also be important. But uncertainties about systems to measure, report and verify soil carbon (MRVs) persist across all financial instruments. And Canada’s public funding for sustainable agriculture lags peer economies.

More reliable measurement, reporting and verification systems (MRVs) will provide the foundation for better insetting and offsetting.

But significant obstacles to MRVs persist, including the lack of standardization.

Betting on the farm:

Leveraging soil to fight climate change

For generations, Canadian farmers have been financially rewarded for the food they produce. The more bushels of wheat a farmer grows—and the greater price that commodity fetches on markets—the larger the return will be.

Yet by embracing sustainable practices, farmers also hold unparalleled power to cut emissions, and to improve air and water quality, soil health and biodiversity.

Tapping that power will require capital. While the current potential of sustainable agriculture is robust, the economics underpinning it are not. We’ll need to price in sustainable practices while supplying the funding and financial instruments to de-risk and incentivize their use. And we’ll need to rethink an economic system that wholly rewards agricultural production while placing little value on preservation.

These efforts—supported by national MRV protocols, and cross-industry partnerships—can be the foundation of a world-leading sustainable agriculture strategy.

What are MRVs?

Measurement: A tool monitors reduction of emissions by farming activity.

Reporting: The measurement is submitted to a third party verifier.

Verification: The third party verifier certifies emissions.

Agriculture could be a much larger source of emissions reduction and removal

Source: Elis (2021). BCG Analysis

What are insets and offsets?

Insets: Organizations directly avoid or reduce emissions within their own supply chains.

Offsets: Companies or individuals purchase tradeable credits generated by renewable energy or other emissions-reducing projects. This credit negates or offsets the same amount of carbon emissions created by the buyer.

Hitting pay dirt:

Three financial pathways to a more sustainable agriculture sector

In this paper, we examine three financial instruments that could boost carbon storage in soil and create other benefits: carbon offsets, carbon insets, and government funding. All of these tools are currently operating at varying scales. However, their potential to make an immediate impact on sustainable farming ranges.

Insetting is currently the most effective mechanism to incentivize farmers to adopt new practices. Though broad consumer demand for sustainable food has yet to develop, agri-food companies have displayed a willingness to pay more for sustainable inputs as a way to reduce emissions in their own supply chains.

Government support will also be critical in the early days of this transition. Yet as it stands, Canadian government funding is lagging that of its global peers. This discrepancy could put Canadian farmers at a disadvantage as sustainable and reliant food systems become more important in the global marketplace. In all cases, reliable measurement, reporting and verification systems (MRVs) are key. Offsets are particularly reliant on MRV trials to build a foundation of market integrity and trust. Developing these systems will take time.

1 | Carbon Offsets

- Short-term: Challenged

- Long-term: Important

[inpage-tabs id=”2″ background_colour=”#ffffff”]

How do carbon offsets work?

- Projects

Projects reduce or remove GHG emissions (for example, through direct air capture, reforestation, sustainable ag practices). Once the projects are validated, credits are issued and then verified by a 3rd party auditor.

- Offsetting

Organizations or individuals can purchase external credits to offset their emissions.

For farmers, the return on offsets doesn’t add up

A farmer using sustainable practices receives roughly $8 to $13 in carbon credits per acre. But due to imperfect science and shaky measurement, a large portion of these credits may be withheld. That’s before multiple project costs deduct as much as 60% (35% for costs, 25% for fees) and another 20% for insurance. In the end, the farmer’s share is just $2 to $4 per acre, a sliver of total farm receipts.

Poor revenue

- ~$8-$13

Carbon credits per acre

Large deductions

Costs – 35%

Costs – 35% Fees – 25%

Fees – 25% Insurance – 20%

Insurance – 20%

Weak incentive

- ~$2-$4

Carbon credit per acre after deductions

Source: Research on North American MRV trials; BCG analysis

The quality of carbon credits hinges on measurement

3 Main Types of MRVs

[inpage-tabs id=”3″]

Framework to identify high quality MRVs

Though every MRV is different, the most effective deploy the following:

| MRV Function | Bronze | Silver | Gold |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil sampling |  |

|

|

| Process-based models |  |

|

|

| At least two 3rd party certifiers to audit findings |  |

|

|

| Remote sensing |  |

|

|

| Assessment of life cycle inputs on farm or more than three best management practices |  |

|

|

| Coverage of more than five field crops |  |

|

|

2 | Insetting

- Short-term: Ready

- Long-term: Important

[inpage-tabs id=”4″]

How sustainably-grown foods can cut supply chain emissions

- Farmers

A network of farmers within a supply chain are selected to farm sustainably by incorporating new practices or expanding them.

- Companies

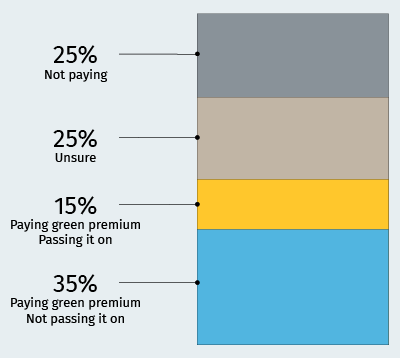

Companies pay farmers more for this food, which helps compensate them for the costs and risk associated with transitioning to sustainable farming. Companies may absorb the added cost of this or pass it on to consumers in the form of a higher price or “green premium”.The process helps companies avoid or reduce Scope 3 emissions in their supply chains and better prepares for them for future regulations that may be more stringent. These supply chain initiatives can also be used for marketing purposes.

- Consumers

Consumers have the option to purchase products that have been grown sustainably.

Most consumers won’t buy for sustainability alone1

- 10%

- of consumers are buying just to “save the planet”.

- 10-30%

- of consumers are willing to buy when sustainability2 is linked to other benefits such as health, safety and quality.

- 40-60%

- of consumers express concern for sustainability but are limited by barriers3 like income, cost and convenience.

1. Including shoppers often/very often purchasing sustainably and considering themselves as sustainable; 2. Including shoppers that sometimes buy sustainably; 3. Includes non-buyers that would be willing to pay a >5% premium at parity of other benefits.

But half of companies, including those in agri-food, will pay more

Source: BCG sustainability consumer survey (June 2022);

BCG project experience and analysis; BCG-WEF Report (2023)

Reasons given to pay green premium

- Meet sustainability commitments (e.g. insets)

- Gain advantage in faster growing markets

- Secure supply ahead of future scarcity

- Prepare for government regulation, (e.g. carbon price)

- Capture customers willing to pay for and/or willing to stop buying for sustainability

3 | Government funding

- Short-term: Ready

- Long-term: Important

[inpage-tabs id=”5″]

Canada’s funding for sustainable agriculture lags peers

United States

Total farm receipts1

$545B

Ag support as a % of receipts

$64B|12%

Climate funding as a

% of total farm receipts

~1.7%

Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) includes $27 billion for agricultural conservation and stewardship through 2031

European Union

Total farm receipts1

$699B

Ag support as a % of receipts

$122B|18%

Climate funding as a

% of total farm receipts

~1.8%

Common Agricultural Policy includes about $224 billion through 2027 for ‘climate-relevant initiatives’

Canada

Total farm receipts1

$83B

Ag support as a % of receipts

$8B|10%

Climate funding as a

% of total farm receipts

~0.5%

The Sustainable Canadian Agricultural Partnership could commit $500M in added funding, and $800 million in On-Farm Climate Action Fund & Ag Clean Tech funding

For more information see appendix

Recommendations:

Harvesting change

Reduced Tillage | Reducing soil disturbance by limiting tilling in croplands improves carbon storage

Nutrient Management | Applying fertilizer from the right source, at the right rate, at the right time, and in the right place, using as little as required

Silvopasture Integrate trees, forage, and livestock grazing in the same area to improve soil nutrients and livestock wellness

Crop rotations | Planting different crops sequentially to improve soil health and nutrients, while combating pests and weeds

Manure Management | Manure can be turned into energy through anaerobic digestion or used as a natural fertilizer

Biochar | Converting crop residue (i.e., waste) to charcoal; when used as a fertilizer, it can increase carbon storage

For more, go to rbc.com/climate.

Download the Report

Contributors:

Lead author: Youssef Aroub, Project Leader, Boston Consulting Group

Boston Consulting Group

Keith Halliday, Director, Centre for Canada’s Future

Chris Fletcher, Managing Director and Partner

Thomas Foucault, Managing Director and Partner

Shalini Unnikrishnan, Managing Director and Partner

Sonya Hoo, Managing Director and Partner

Pilar Pedrinelli, Consultant

RBC

Darren Chow, Senior Manager, Digital Media

Naomi Powell, Managing Editor, Economics and Thought Leadership

Mohamad Yaghi, Agriculture and Climate Policy Lead

Colin Guldimann, Economist

Trinh Theresa Do, Senior Manager, Thought Leadership Strategy

Zeba Khan, Digital Publishing

Aidan Smith-Edgell, Research Associate

Shiplu Talukder, Digital Publishing Specialist

Gwen Paddock, Director, Sustainability & Climate – Agriculture

Arrell Food Institute, University of Guelph

Evan Fraser, Director

Ibrahim Mohammed, Ph.D. Candidate, Environmental Sciences

Deus Mugabe, Ph.D. Candidate, Plant Agriculture

Lisa Ashton, Ph.D. Candidate

In addition to those cited in this report, we’d like to thank the following individuals for their insights:

-

- Alison Sunstrum, Founder, CEO CNSRVX-Inc

- Dan Lussier, Director, Canadian Agri-Food Data Initiative

- Tim Faveri, Global VP, Sustainability & Stakeholder Relations

- Michelle Nutting, Director, Agricultural and Environmental Sustainability, Nutrien Ltd.

- Karen Haugen-Kozyra, President Viresco Solutions

- Dr. Brian McConkey, Chief Scientist, Viresco Solutions

- Anthony D’Agostino, Director – Commodity Markets, RBC

- Marty Seymour, COO, Carbon RX

- Gillian Flies, Co-Founder, Farmers for Climate Solutions

- Matt Sawyer, fourth generation farmer, Acme, Alberta

- Doug Whitehead, crop farmer, Manitoba

- Julia Maria-Becker, Senior Manager, Sustainable Enterprise Solutions, RBC

- Janay Meisser, Director of Innovation, United Farmers of Alberta

- Derek Eaton, Director of Industrial Policy, The Transition Accelerator

- Ryan Cooke, Research Associate, Smart Prosperity Institute

- David Hughes, President and CEO, The Natural Step Canada

- Kristjan Hebert, Managing Partner, Hebert Grain Ventures

Appendix

The Sustainable Canadian Agricultural Partnership includes $3 billion over 5 years. About $1 billion is through federal programs and activities, of which $690M goes to innovative and sustainable growth including the AgriScience program to tackle pre-commercial and other research. About $2 billion is dedicated to supporting sustainable agriculture, equipment purchases, training, and scientific research.The $200 million On-Farm Climate Action Fund was distributed through 12 organizations across Canada. These will dispense money to help farmers adopt sustainable practices. Provinces are also establishing or managing their own carbon trading systems where producers can sell agricultural carbon credits. Alberta and Quebec’s offset systems are well established, while Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan are in the process of launching their own approaches.

United States

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is the largest piece of federal legislation to ever address climate change, increasing the pool of funding for conservation efforts by US$20 billion. It expands the Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities program which seeks to remove 50 million metric tons of carbon dioxide. It has allocated US$3 billion to 141 projects on crop and livestock farms across all 50 states and Puerto Rico. And it involves collaboration among more than 100 universities, 20 tribes and tribal groups, and 60,000 farms, on over 25 million acres of working land. The project will remove the emissions amounting to the equivalent of 12 million gas-powered vehicles.

European Union

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) program was revamped in 2022. It includes €387 billion, a third of the EU’s entire 2021-2027 budget, to assist in the transition to Net Zero farms and rural communities. Its goal is to cut greenhouse gases by 55% by 2030—in line with EU’s Green Deal targets. In all, 40% of the CAP’s financial plan is explicitly dedicated to climate relevant activities and a further 10% of the EU’s budget outside the CAP is directed towards biodiversity efforts.

Australia

The Emissions Reduction Fund is Australia’s flagship program for fighting climate change. It supports farmers, businesses, and rural communities in decreasing greenhouse gases by providing carbon credit units that can be sold on to public or private buyers. The scheme actively promotes soil carbon projects by sharing the upfront costs of soil sampling. The program expects Australian farmers to earn over AUD 400 million from the sale of credits from soil carbon sequestration by 2050. The federal government is also dedicating AUD 64 million in funding to promote the development of soil carbon measurement technologies and an additional AUD 54.4 million to encourage active soil testing and national data sharing.

Brazil

Brazil is offering farmers low-interest loans through the ABC Plan. Farmers are given credit and financing options to adopt sustainable farming practices like no-till, intercropping, crop rotation, and recovering degraded pastures. Launched in 2010, the program was recently revamped with the goal of storing 41MT annually of carbon dioxide over 177 million acres of farmland across the country. In its last financing round, over 62,000 contracts were signed. This made Brazil the second highest ranked nation in the world for no till farms (around 18% of Brazil’s total agricultural land).

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates. This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward- looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social- impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.