Pandemic forces reshaped Canada’s workforce

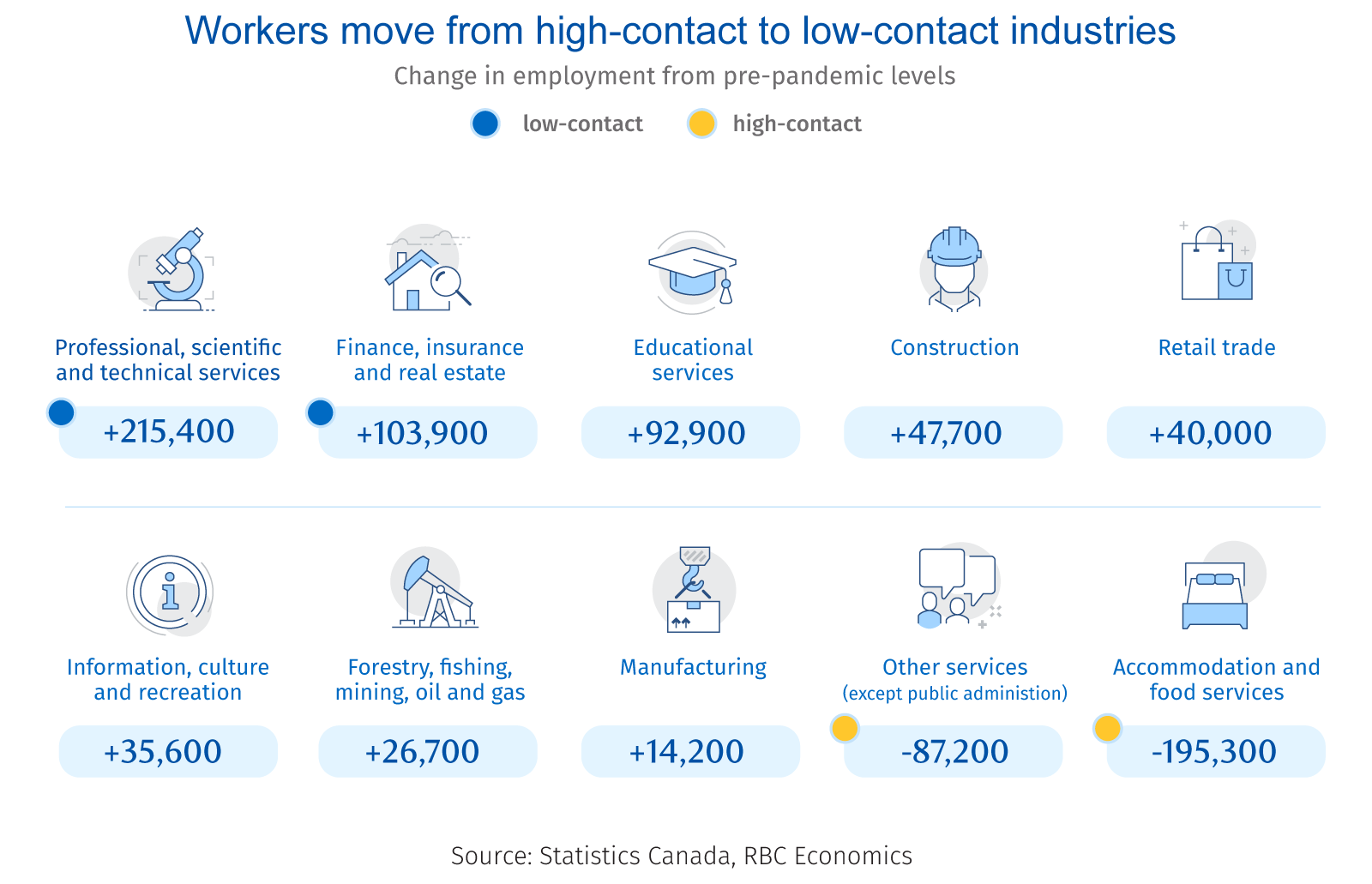

COVID-19 transformed how, where, and in what industries the average Canadian works. From the outset, the crisis prompted widespread restrictions that pushed a significant number of workers out of “high-contact” travel and hospitality sectors. Employment in accommodation and food services, for example, was still running 195,000 below pre-pandemic levels as of March.

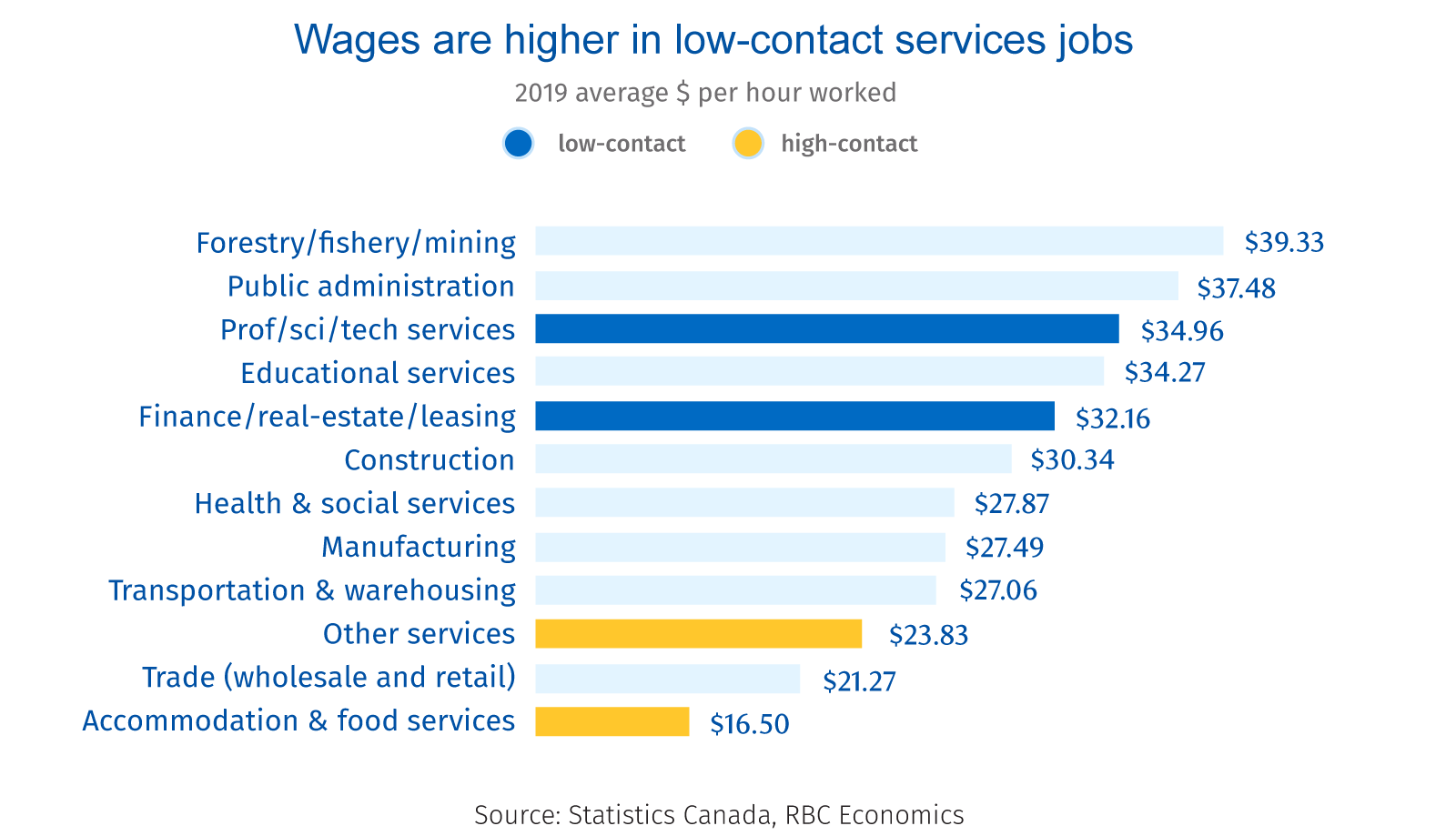

But that shortfall has been more than offset by a surge in professional and technical services jobs—which jumped by 215,000 over the same period. Wages in these occupations are double that of accommodation and food services on average. Output per hour (productivity) is also twice as high.

And in addition to shifting into these higher-paid sectors, workers are also moving into higher-paid jobs within them—shifting out of sales and service positions for instance, and into business, finance and administrative roles.

The economic impact of this shakeup has been significant, accounting for 2% of total wage growth of 8% over two years of the pandemic. It’s also provided a $20 billion boost to annual household wage income.

High post-secondary education levels will continue to fuel the transition

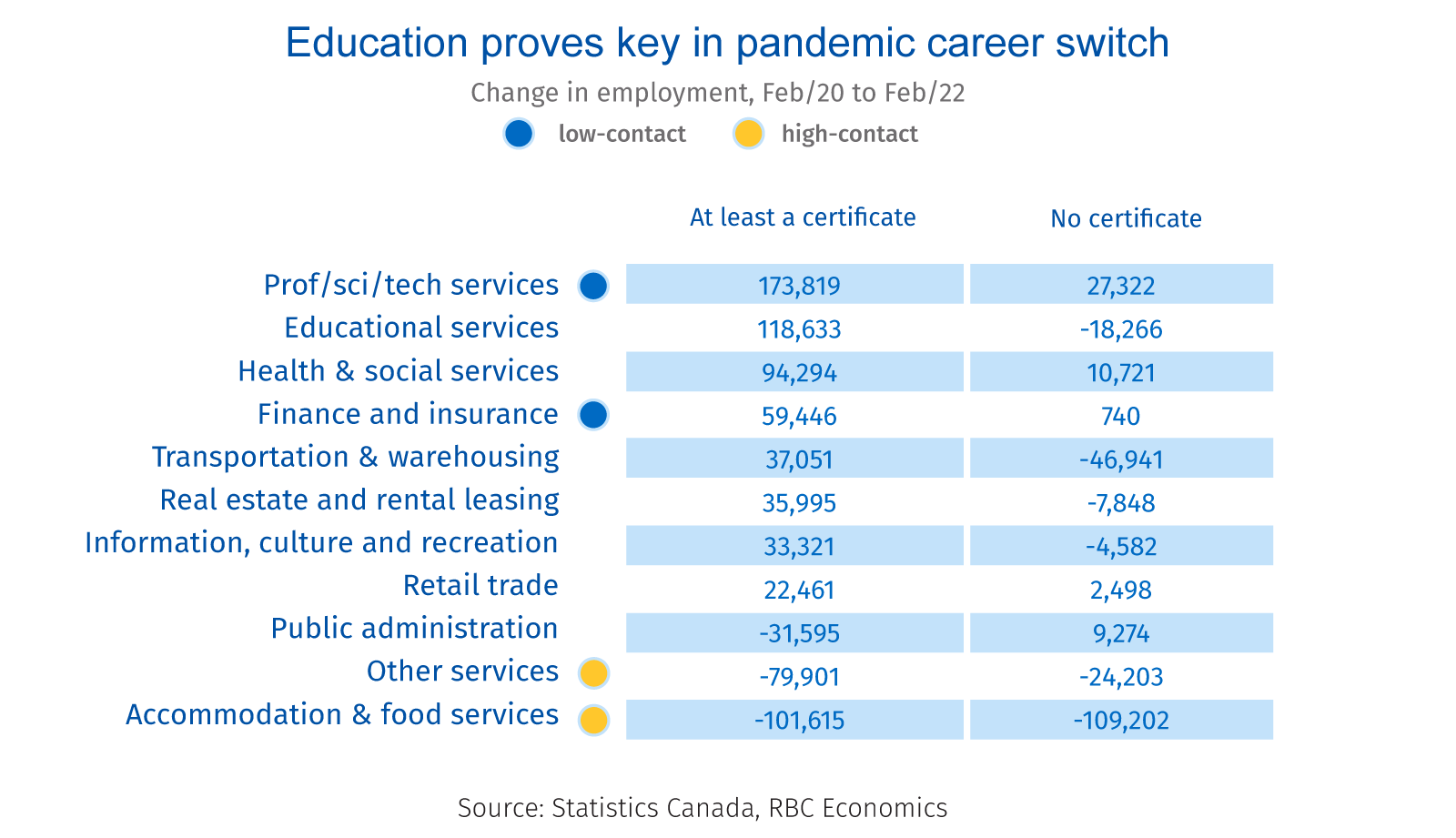

Education has been the key for workers seeking higher-paid positions. While the number of employees with post-secondary degrees or certificates has fallen sharply in high-contact services, it’s increased even more dramatically in low-contact industries. This includes professional and technical services as well as finance and insurance. Previously under-utilized, these workers’ post-secondary education is now being put to greater use—bettering overall productivity.

And demand for those low-contact jobs has remained exceptionally strong. Commercial services exports, which include financial, R&D and consulting services, fell just 2% over the first half of 2020, compared to a 27% plunge in goods exports. And these exports haven’t just been more resilient to pandemic headwinds, they’ve continued to grow into a bigger share of overall exports—now accounting for over 15% of total Canadian exports ex-energy products (up from just 9% in 2007.) Though they were equivalent to auto exports prior to the pandemic (February 2020), they now surpass them in size.

Low-contact services jobs typically rely more on human capital (i.e. education and training) to drive productivity. As a result, Canada’s highly-educated workforce has been uniquely positioned to benefit. Roughly 60% of Canadians between 25 and 64 received some form of post-secondary education in 2020, the highest proportion in the OECD.

By comparison, workers without completed post-secondary education haven’t captured the same opportunities. The shortfall in employment among those without post-secondary education is still around 250,000 compared to pre-pandemic levels.

Here to stay: Job market shifts are expected to outlast the pandemic

With demand for low-contact services holding up, it’s difficult to see the large-scale shift in the labour market coming undone. Fortunately, the pandemic has only accelerated a long-run increase in school enrollment rates. Among 15-24 year-olds, these rates hit record levels in 2020 and 2021.

For Canada, this will add to an already higher share of more educated workers—paving the way for higher productivity gains in the future.

In the meantime, high-contact services will continue to struggle to find workers. But jobs within these sectors were already at higher risk of automation-related transformation to begin with, a StatCan report found. For these industries, the pandemic could act as an accelerator, pushing them to innovate by investing in automation.

Claire Fan is an economist at RBC. She focuses on macroeconomic trends and is responsible for projecting key indicators on GDP, labour markets as well as inflation for both Canada and the US.

Nathan Janzen is a member of the macroeconomic analysis group. His focus is on analysis and forecasting macroeconomic developments in Canada and the United States.

Naomi Powell is responsible for editing and writing pieces for RBC Economics and Thought Leadership. Prior to joining RBC, she worked as a business journalist in Canada and Europe, most recently reporting on international trade and economics for the Financial Post.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates. This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward- looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social- impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.