Highlights:

- The government boosted its pandemic action plan by $15 billion to $45 billion over three years

- More money is allocated to fight COVID-19, support people and businesses, and stimulate the economy

- This year’s projected budget deficit is $38.5 billion—a record high

- The budget shortfall is projected to decrease modestly over the next two years

- Despite escalating debt, interest on debt will rise only slightly as a share of revenue

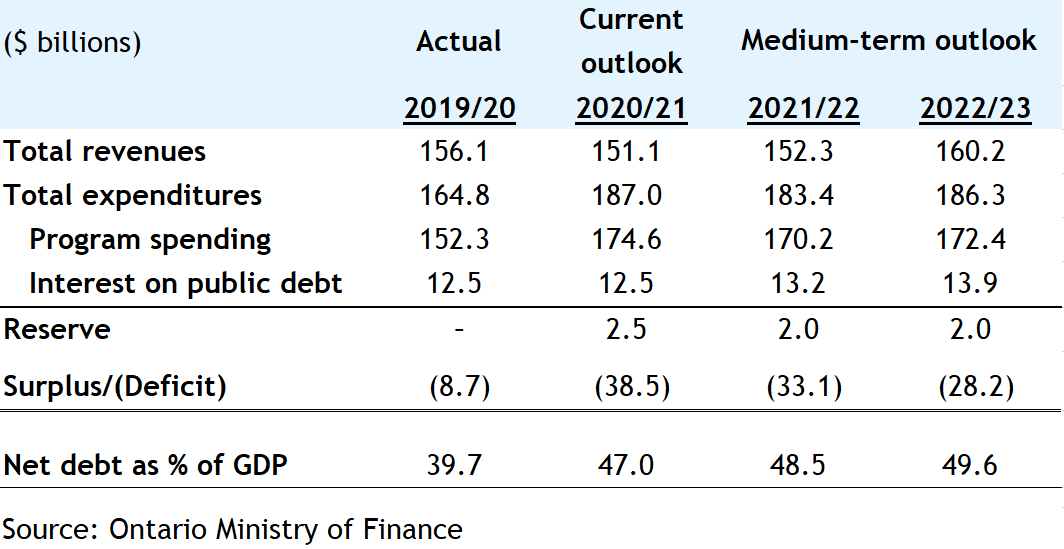

Fighting the pandemic, and helping people, businesses and the economy back on their feet will take a heavy toll on Ontario’s finances. This came out loud and clear in the 2020 budget—delivered eight months later than usual. The budget projects record deficits this year (-$38.5 billion) and in the next two (-$33.1 billion and -$28.2 billion, respectively) as spending soars and revenues drop. Net debt will balloon by $120 billion by 2022-2023. Yet this was largely expected. The fiscal update released at the end of March (in lieu of a full-blown budget) and August’s first quarter report already painted a bleak picture. If anything, the situation appears to have stabilized as the latest projection for this year’s deficit (-$38.5 billion) is unchanged from August.

The government’s pandemic action plan took centre stage in Budget 2020. This was in reality the third round of the plan first introduced in March and subsequently updated in August, nearly tripling in size from the initial $17 billion in the process. This budget expanded it by $15 billion to $45 billion over three years. All three pillars of the plan—protect, support and recover—are getting more money. Protecting Ontarians is seeing the biggest increase ($7.5 billion) which will mainly go to the fight against COVID-19 and support for long-term care residents. The government is also boosting assistance to families, workers and businesses to the tune of $2.4 billion, and adding $4.8 billion to economic recovery efforts like investing in broadband infrastructure, lowering electricity rates for many businesses and subsidizing tourism expenses in Ontario.

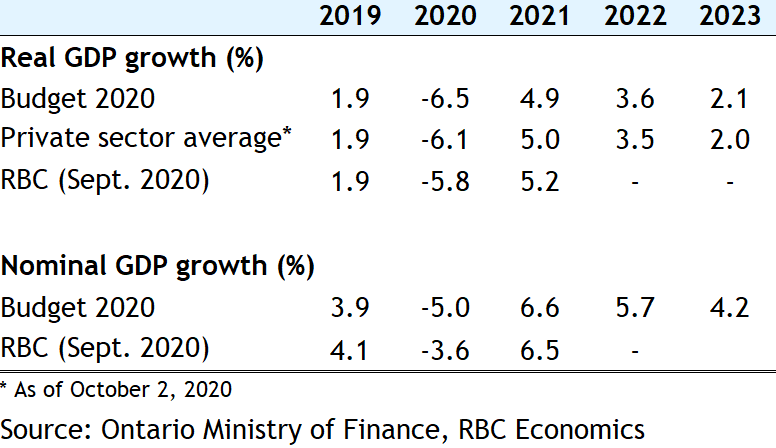

Economic Growth Assumptions

In all, program expenditures are projected to jump $22 billion (14.6%) this fiscal year. Revenues will fall $5.0 billion (-3.2%) from 2019-2020, led by declines of $5.4 billion (-36%) in corporate tax and $3.7 billion (-13%) in sales tax. The overall revenue drop would have been much larger ($13 billion or –9.9%) had it not been for a massive $10.8 billion (31%) increase in federal transfers. Budget 2020 projects interest on public debt to stay unchanged at $12.5 billion despite net debt rising 13% to $398 billion. This is because the government is able to borrow at lower interest rates—the effective interest rate on total debt is expected to fall from 3.4% last year to 3.0% this year.

These highly unusual times make it very difficult for a government to plan ahead. Budget 2020 builds in several prudence measures to cushion against unforeseen developments, including $10.3 billion in special contingency funds in 2020-2021 (falling to $5 billion in 2021-2022 and $2.8 billion in 2022-2023), and a $2.5 billion contingency reserve (falling to $2 billion in the following two years). The budget even provides two alternative economic scenarios and corresponding deficit projections for the next two years. In the slower growth scenario (GDP growing at rates of 3.3%, 1.0% and 1.4% in the next three years), Ontario’s budget shortfall is $2.5 billion and $5.2 billion larger than the base case in 2021-2022 and 2022-2023, respectively. In the faster growth scenario (GDP growing at rates of 7.5%, 3.1% and 2.3%), the deficit is $5.4 billion and $6.9 billion smaller, respectively. The central economic scenario (shown in our table on the first page) itself is conservative—as a standard practice, the government sets the economic growth profile it uses for planning purposes slightly below the private sector’s average. While the fiscal plan isn’t shock-proof, we believe the inclusion of significant prudence measures is the right approach in the current circumstances.

To fund the higher deficit and ongoing capital plan, the government is pegging its total long-term public borrowing at $52.3 billion this year, little changed from the August first quarter report estimate. It expects this will increase to $58.6 billion in 2021-2022 and $59.3 billion in 2022-2023. These amounts will handily exceed the $43.8 billion recorded at the depth of the Great Recession in 2008-2009. Net debt is projected to balloon 34% by 2022-2023. As a share of GDP, it will surge from 39.7% in 2019-2020 to 47.0% in 2020-2021, reaching 49.6% by 2022-2023. Despite rapidly mounting debt, interest on debt will rise only slightly as a share of revenue from 8.0% last year to 8.2% this year and 8.7% in the next two years—just marginally above the past decade’s average (8.6%).

There will be plenty of work to do in future budgets to address Ontario’s fiscal situation and bring it on a stronger longer-term footing. But for now at least, exceptionally low interest rates help Ontario (and other provinces) to afford doing whatever it takes to combat COVID-19, assist Ontarians and businesses, and stimulate the economy without having to cut back on other important missions. The guiding principles (or pillars) Budget 2020—protect, support and recover—are the right ones for the times. Flexibility and readiness to do more if needed might be others. But interest rates won’t stay this low forever. The post-COVID-19 chapter, whenever it begins, will be all about an exit plan. And the task at hand won’t be any easier.

Ontario’s fiscal plan

Read report PDF

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates. This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward- looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social- impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.