- Proof Point: Straying from fiscal budget anchors negatively impacts governments’ credibility and makes their borrowing more expensive—potentially raising lending risks for bond investors. Any rise in the federal government’s funding costs will trickle down to businesses and households.

- Recent provincial budgets have generally painted a deteriorating fiscal picture. A softer economy and rapidly increasing expenses have weighed heavily on fiscal balances and inflated government debt.

- There’s no doubt the federal government is under similar pressure, but it must show discipline in the upcoming budget. It should not take its status as a top-rated sovereign for granted.

Governments stray from fiscal guardrails

The federal government and most large provinces have set fiscal anchors to address high indebtedness and ensure they maintain flexibility over the long term. These anchors range significantly in their stringency from broad direction for the debt load (as set at the federal level) to specific indebtedness (most commonly the net debt-to-GDP ratio) and interest bite metrics. In most cases, they’re in place to keep provincial and federal debt loads in check—building credibility and instilling confidence in voters and financial markets.

The federal government and governments of Ontario, Quebec, Alberta, and Manitoba are among those that have introduced fiscal guardrails, but staying within them has become more challenging. Ontario, for example, breached one of its fiscal anchors (net debt-to-revenue ratio of less than 200%) in its 2024 budget just one year after tightening up this measure. Quebec and Manitoba are also drifting away from their targets, sending negative signals to bond investors.

Weaker economy, inflation weigh on public finances

The pandemic and its economic impact tremendously disrupted governments’ revenues and expenditures. The initial health crisis and economic hit led to massive deficits. But historical support measures and the lifting of lockdowns paved the way for a speedy economic recovery that fueled government coffers. Spiking inflation helped too (at first) as sharp increases to the price of goods and services lifted government revenues through a higher sales tax base.

That revenue windfall is now over. Public sector finances are eroding as nominal gross domestic product growth slows and high inflation adds pressure to the expense side of the ledger.

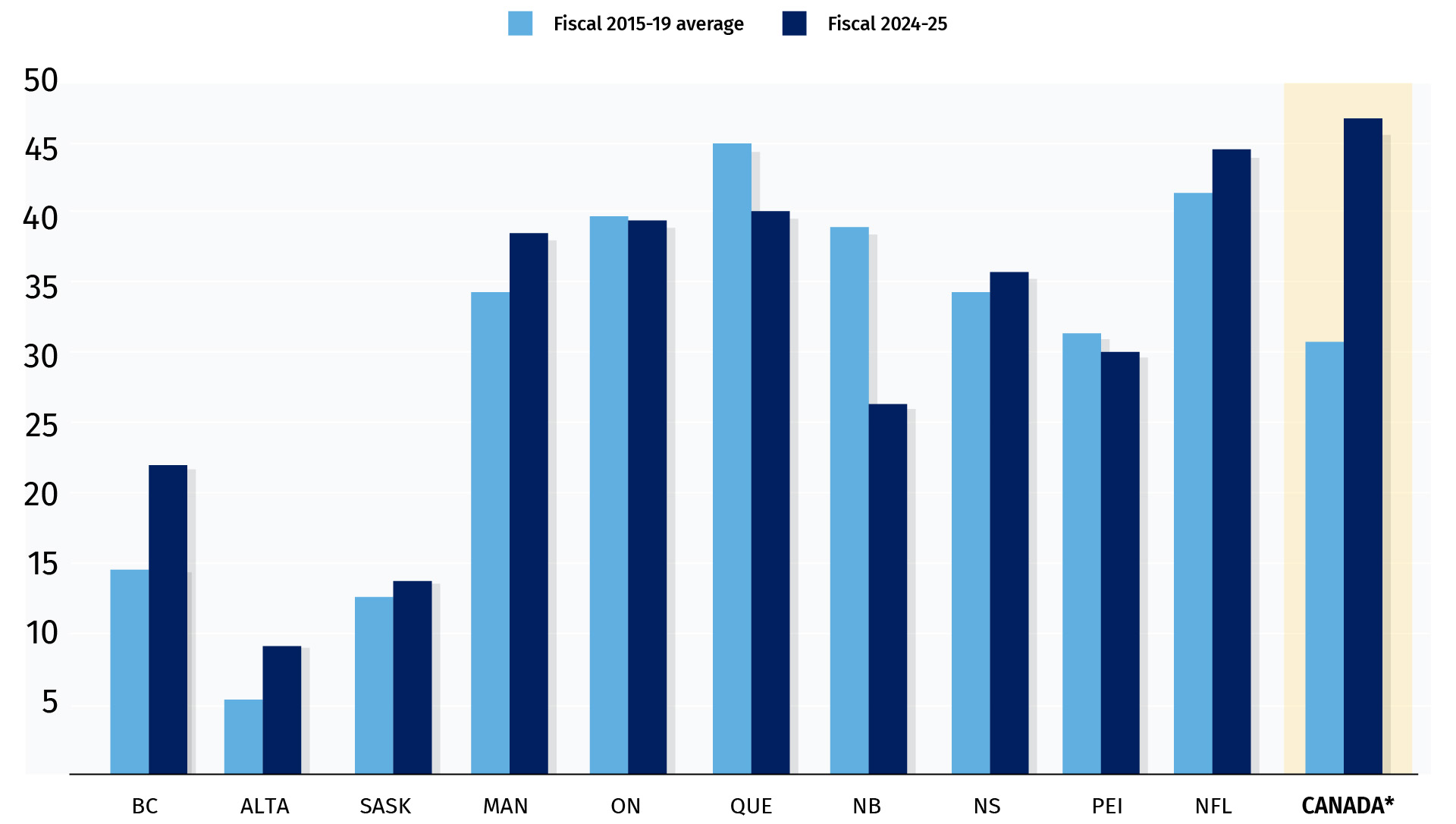

Government indebtedness up from pre-pandemic levels

in most jurisdictions

Net debt-to-GDP, %

Source: Provincial Public Accounts, 2024 Budget, RBC Economics

*: Fall Economic Statement

As a result, most provinces are carrying heavier debt burdens compared to pre-pandemic levels. And to make matters worse, all provinces (except Alberta and New Brunswick) now expect to grow their net debt burden until at least fiscal 2025-26. Odds are the upcoming federal budget will include upward revisions to its debt burden as well—leaving little wiggle room to abide by fiscal guardrails.

Some provinces will pay more to service debt

Negative developments to public finances often lead to an increase in funding costs for governments (all else constant). Large budget shortfalls enlarge borrowing requirements and the supply of government bonds—pushing down bond prices and raising yields if investor appetite for their bonds don’t grow at the same time. That may also impact the risk associated with Canadian debt relative to other countries because bond investors want to get compensated for by bidding up yields relative to other jurisdictions.

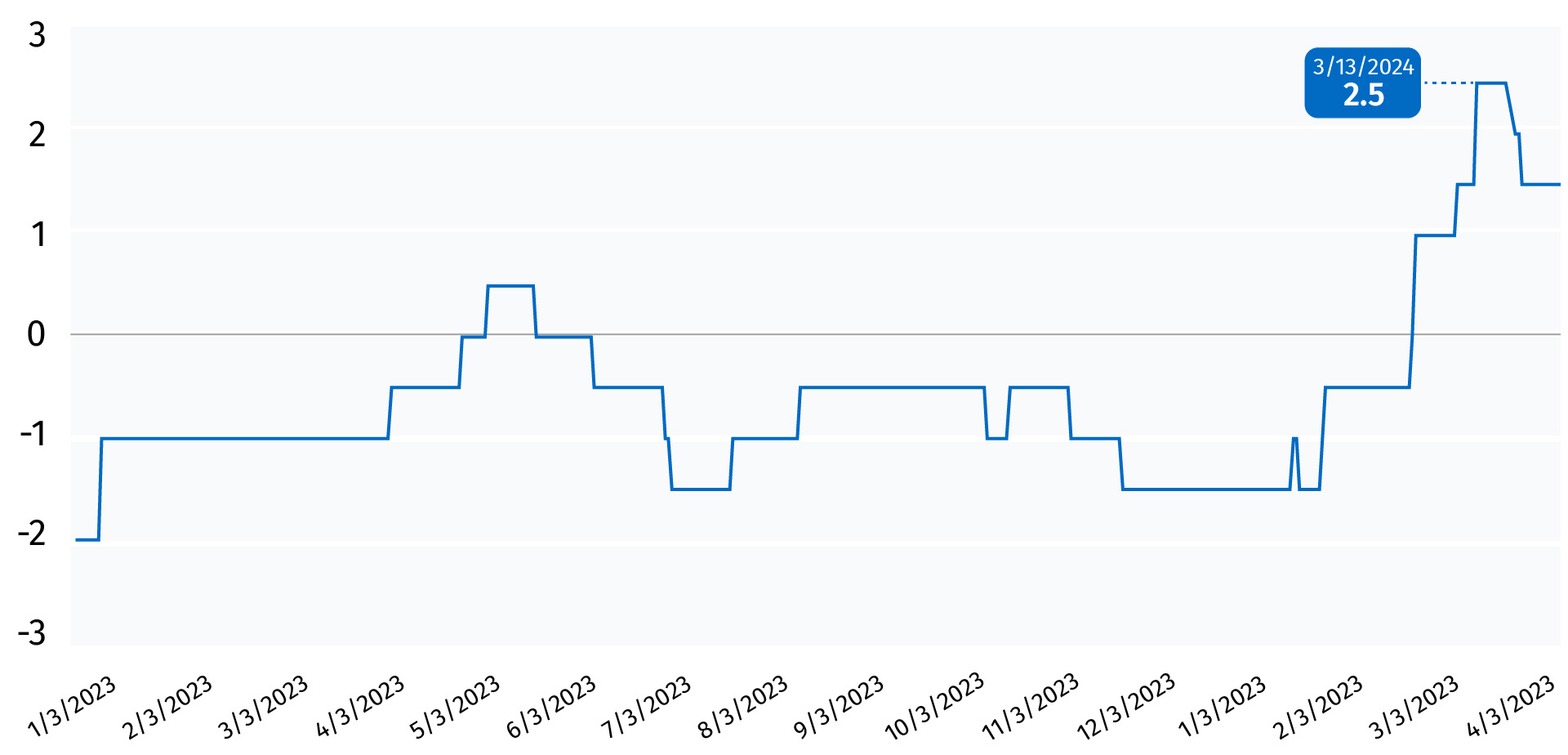

We’ve already seen this at the provincial level. Quebec’s 2024 budget (which was released on March 12 ahead of Ontario’s) included plans to grow the debt burden, moving the government further away from its target of reaching a 30% net debt-to-GDP ratio by 2037-38.

The province’s deteriorating fiscal picture—and growing borrowing requirements— was quickly priced into bond markets, bringing the spread between Ontario and Quebec 10-year bond yields up to their highest differential in over a year. As a result, the Quebec government will, once again, pay more to service its debt relative to Ontario.

Spread on 10yr Quebec vs. Ontario bonds diverge

following Quebec Budget

Quebec vs. Ontario 10-year bond spread, basis points

Source: RBC Economics

Higher debt servicing costs will trickle down to households and businesses

The development in Quebec should not be lost on the federal government as it puts together its fiscal plan. Any signs of a loosening grip on the public purse will result in a similar reaction from bond markets—bringing up the relative borrowing cost on Canada’s sovereign debt.

Though Canada holds a strong sovereign rating going into next week’s budget, key metrics indicate its fiscal position is among the more vulnerable relative to other AAA rated economies. This suggests Canada is at a greater risk of a downgrade than other top-rated peers.

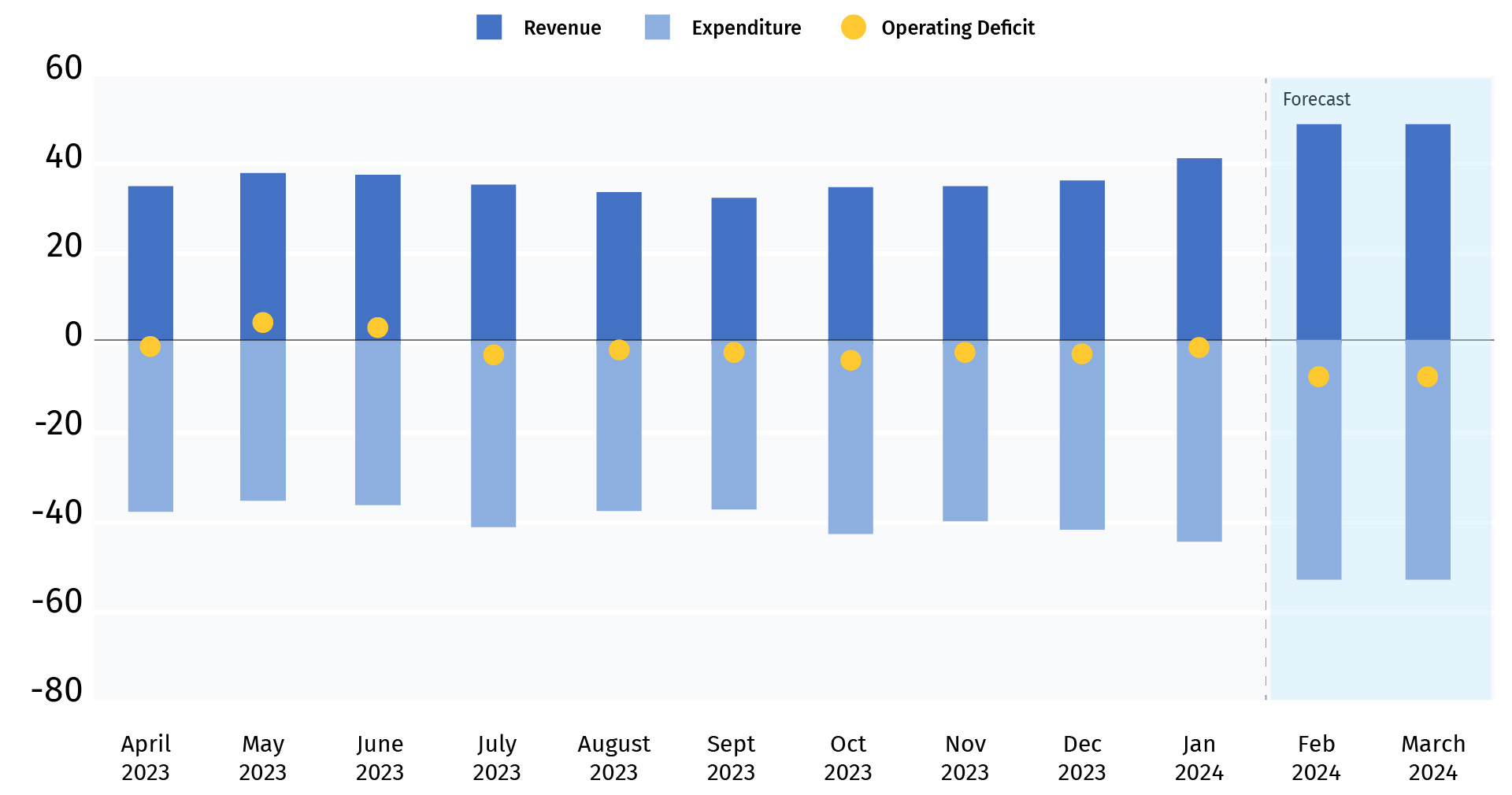

Will Feds see revenue increase they need to hit deficit target?

Government of Canada monthly revenue and expenditure fiscal 2023-24, billions of dollars

Source: Government of Canada Fiscal Monitor, RBC Economics

Even though deeper deficits and higher associated sovereign borrowing costs may feel like a distant problem for many Canadians, the impact has the potential to trickle down to most households and businesses.

The federal government plays a special role in financial markets. Its so-called sovereign rating affects borrowing rates for all subnational entities including provincial governments and large borrowers such as banks. The latter’s rates charged to customers—for mortgages and other loans—are closely correlated to the sovereign’s rating.

Therefore, all Canadians have a stake in seeing the federal government meet its fiscal targets. We hope Ottawa shows fiscal discipline in next week’s budget.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates. This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward- looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social- impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.