- Canadian business investment is only now recovering from a steep 19% pandemic plunge.

- Dogged labour shortages are pushing businesses to invest more despite recession worries.

- But those plans could still be upended amid recent financial market stress.

- And the economy can’t afford another period of weak business investment.

- The bottom line: We continue to expect a recession this year, but a mild one that brings relative outperformance of business investment. With already weak productivity trends only softening further due to the pandemic shock, we’ll need it.

Central bank rate decisions are key to maintaining investment

Recession fears or not, Canadian businesses are looking to invest more in their operations this year. And given the pressures we’re facing, that’s a very good thing for future productivity growth. Demographic headwinds mean labour will remain in chronic short supply, making better-equipped, more efficient operations essential. Indeed, the baby boom generation is already hitting retirement age in greater numbers. And sluggish growth in available hours worked means businesses will need to use those hours more efficiently.

The recent bout of financial market stress has central banks, like the U.S. Federal Reserve, re-thinking how high to push interest rates. They are walking a fine line between under-hiking rates (and failing to get inflation under control), and over-tightening (causing a larger economic downturn than necessary). One of the key reasons to fear the latter—beyond the obvious direct effect of higher unemployment—is that it could prompt businesses to tighten their belts at a time when we need them to invest. This would leave a lasting bruise on productivity growth in the years ahead.

Periods of weak investment damage our long-term competitiveness

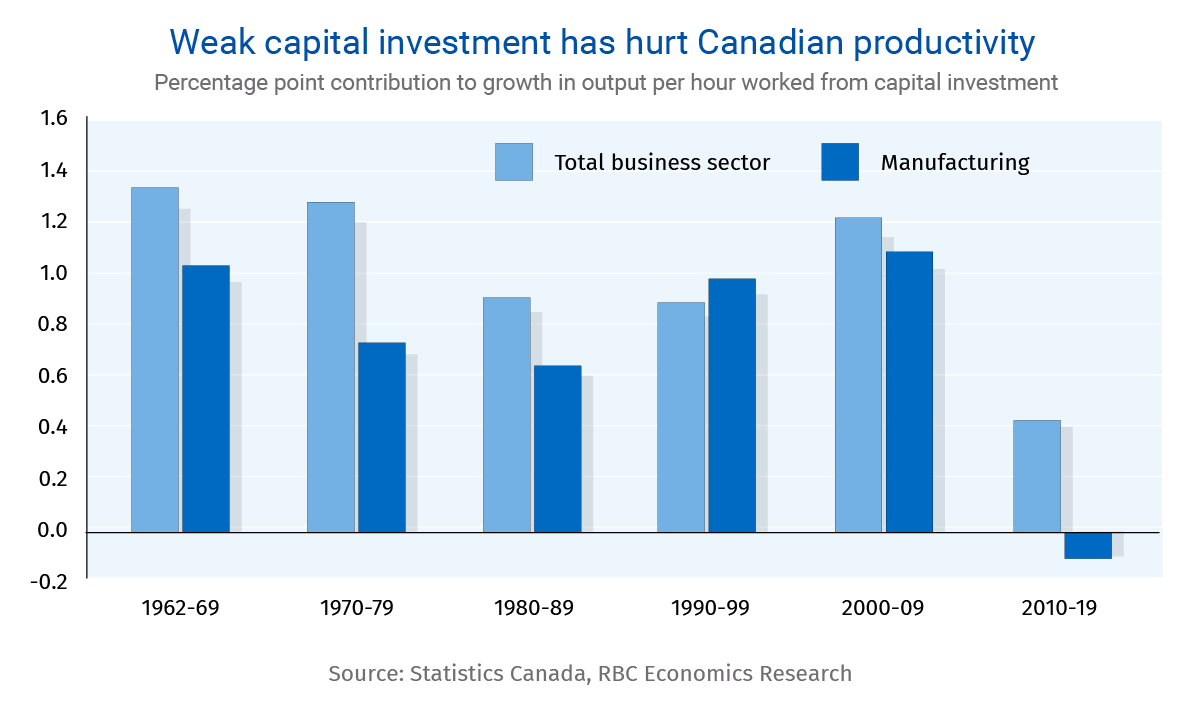

Canadian business investment is just now recovering from a precipitous 19% pandemic drop. But a return to the status quo (i.e. pre-pandemic levels) won’t be enough to hold our ground against these forces. The 23% decline in Canadian business investment following the 2008/09 recession—and the slow recovery that followed—was still dragging on worker productivity growth heading into pandemic. In the decade leading into the crisis, the contribution of capital investment to growth in output per hour worked was just 0.4% per year, a third of the decade prior. In the capital-intensive manufacturing sector, it outright declined.

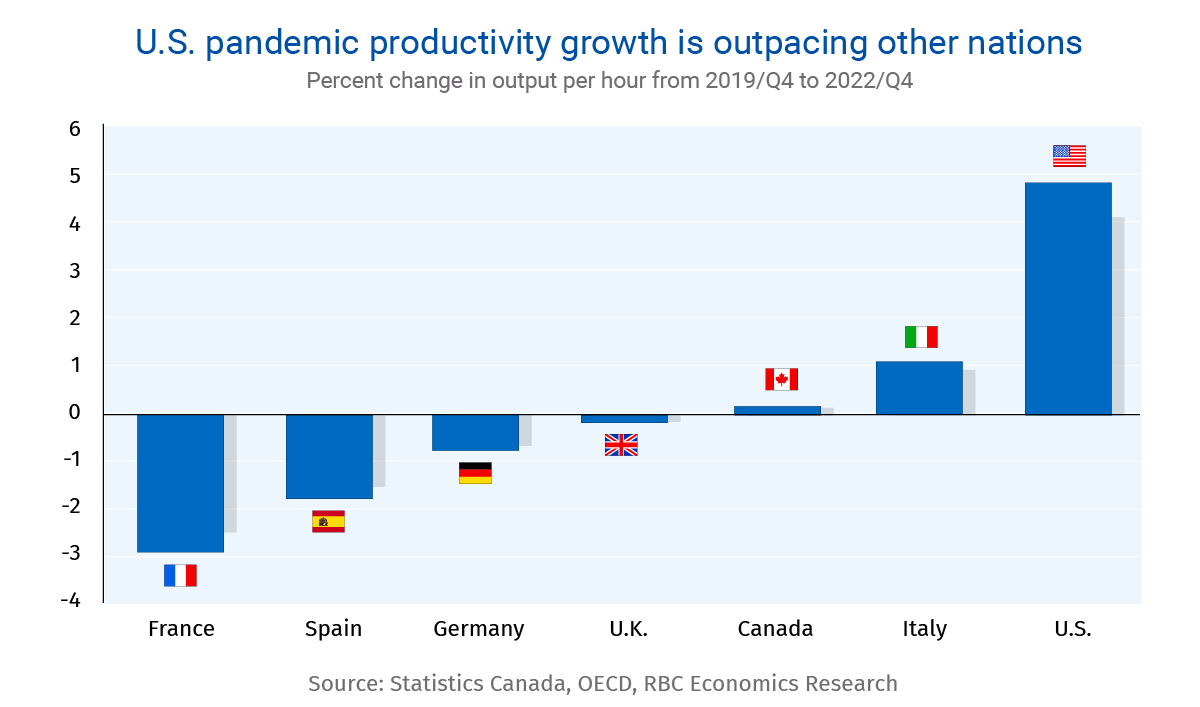

Canada’s productivity performance since the pandemic has been lacklustre. Output per hour at the end of 2022 was essentially unchanged from pre-pandemic (Q4/2019) levels despite a large shift of workers into industries with higher productivity. Though broadly in line with the experience of most other G7 economies, that’s well behind a 4% jump in output per hour worked in the U.S.

Another bout of soft investment spending would further weigh on Canadian worker productivity—just as an aging population intensifies labour shortages.

Canadian business investment to outperform in a ‘mild’ recession

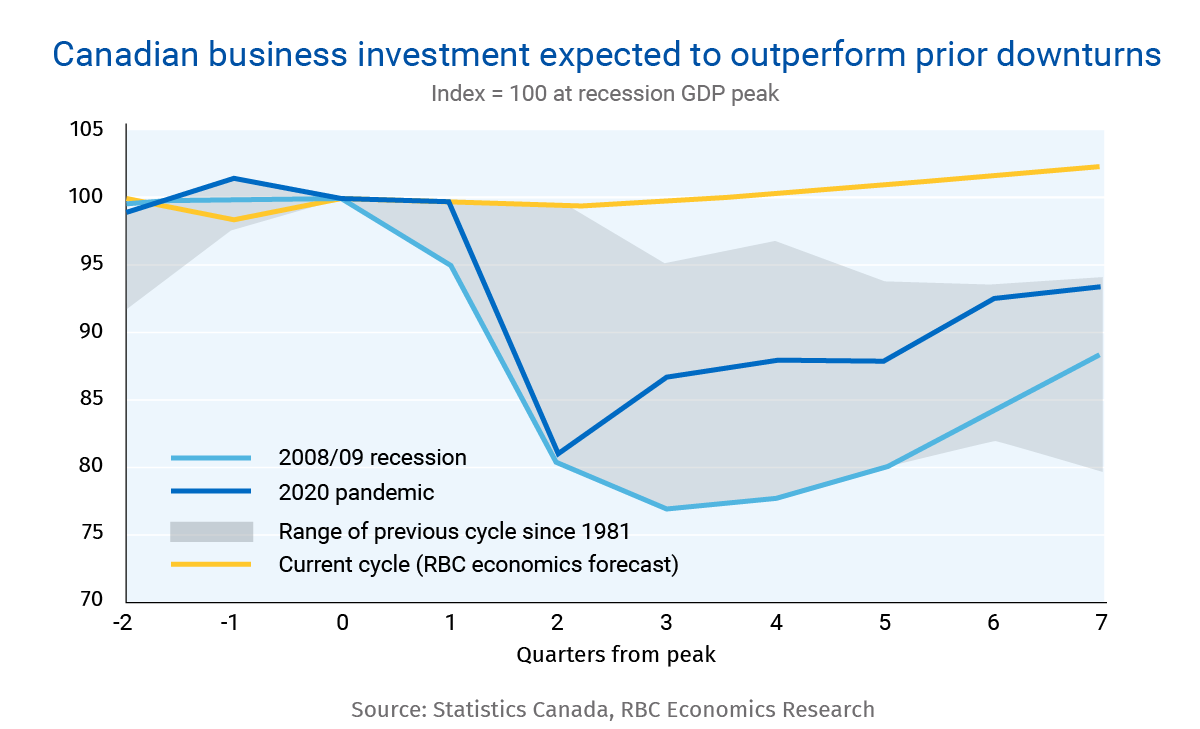

In the Bank of Canada’s Business Outlook Survey, firms put high odds on a recession arriving this year. Their investment plans nevertheless remain positive. Businesses plan to spend 4.3% more this year than last, according to Statistics Canada’s annual capital expenditure intentions survey. That’s consistent with our own forecast for a 1.5% increase in business investment in 2023 (excluding price impacts.) While not exactly strong, that would mark the first time on record that business investment outperformed GDP growth during a recession. In Canadian recessions dating back to 1981, investment fell at an average of three times GDP.

There’s greater optimism this time around, partly because the coming economic downturn is expected to be ‘mild’ and, for now, order books are still full. But businesses are also keenly aware that labour shortages have been a persistent, and intensifying, challenge for most of the last decade and will remain after the next downturn.

Businesses have plenty of cash to spend

Businesses can’t spend more without funding, and rising interest rates have made borrowing more expensive. But corporate profits have also been very strong: almost 30% above pre-pandemic levels as of Q4 2022. And businesses’ cash savings are generous. Non-financial corporate holdings of cash and short-term securities were worth almost a third of annual Canadian GDP late last year compared to nearly a quarter prior to the pandemic. And the 2023 federal budget unveiled significant tax credit programs to lower the cost of investments in the low carbon economy.

The future cost of not investing now is also rising. The prospect of a persistently tight labour market means continual upward pressure on wages. That makes productivity-enhancing investments look cheaper on a relative basis, even at higher interest rates. Recent financial market turmoil tied to the failure of U.S. regional banks has pushed credit spreads (the rate that businesses pay to borrow minus the ‘risk-free’ government rate) higher. But these spreads are still at manageable levels. And central banks are well-equipped to deal with that credit market stress if it were to intensify.

It’s worth noting that business investment isn’t the only way to achieve efficiency gains. Better utilization of immigrant skills, for example, could offer a significant boost to productivity. And the economy can’t afford another lost decade of productivity growth.

Nathan Janzen is an Assistant Chief Economist, leading the macroeconomic analysis group. His focus is on analysis and forecasting macroeconomic developments in Canada and the United States. Nathan has been with RBC since 2008 with a focus on covering the macroeconomic outlook for Canada and the United States. He has a MA in economics from McMaster University and a BA in economics from the University of Regina.

Abbey Xu is an economist at RBC. She focuses on macroeconomic models as inputs into the Bank’s forward looking provisioning for credit losses and stress testing process. Her education background includes a MA in Business Economics, and a BA in Economics from Wilfrid Laurier University.

Proof Point is edited by Edited by Naomi Powell, Managing Editor of RBC Economics & Thought Leadership.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates. This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward- looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social- impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.