- The ranks of Canadian renters is growing fast. Though two-thirds of Canadian households owned their home in 2021, renters have increased at three times the rate of homeowners in the past decade.

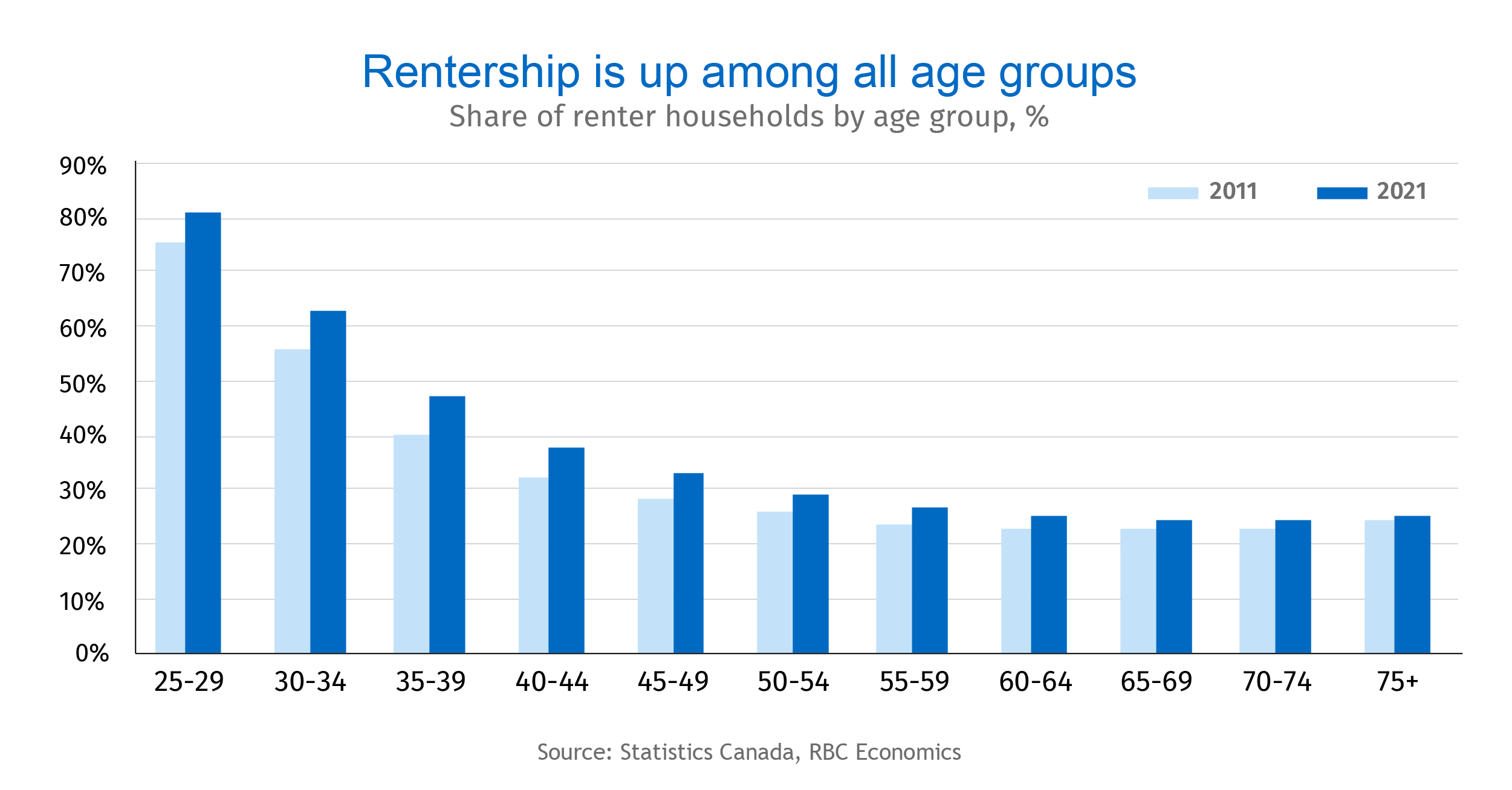

- The shift to renting has been widespread across age groups and areas, though younger Canadians and urbanites still make up the largest group.

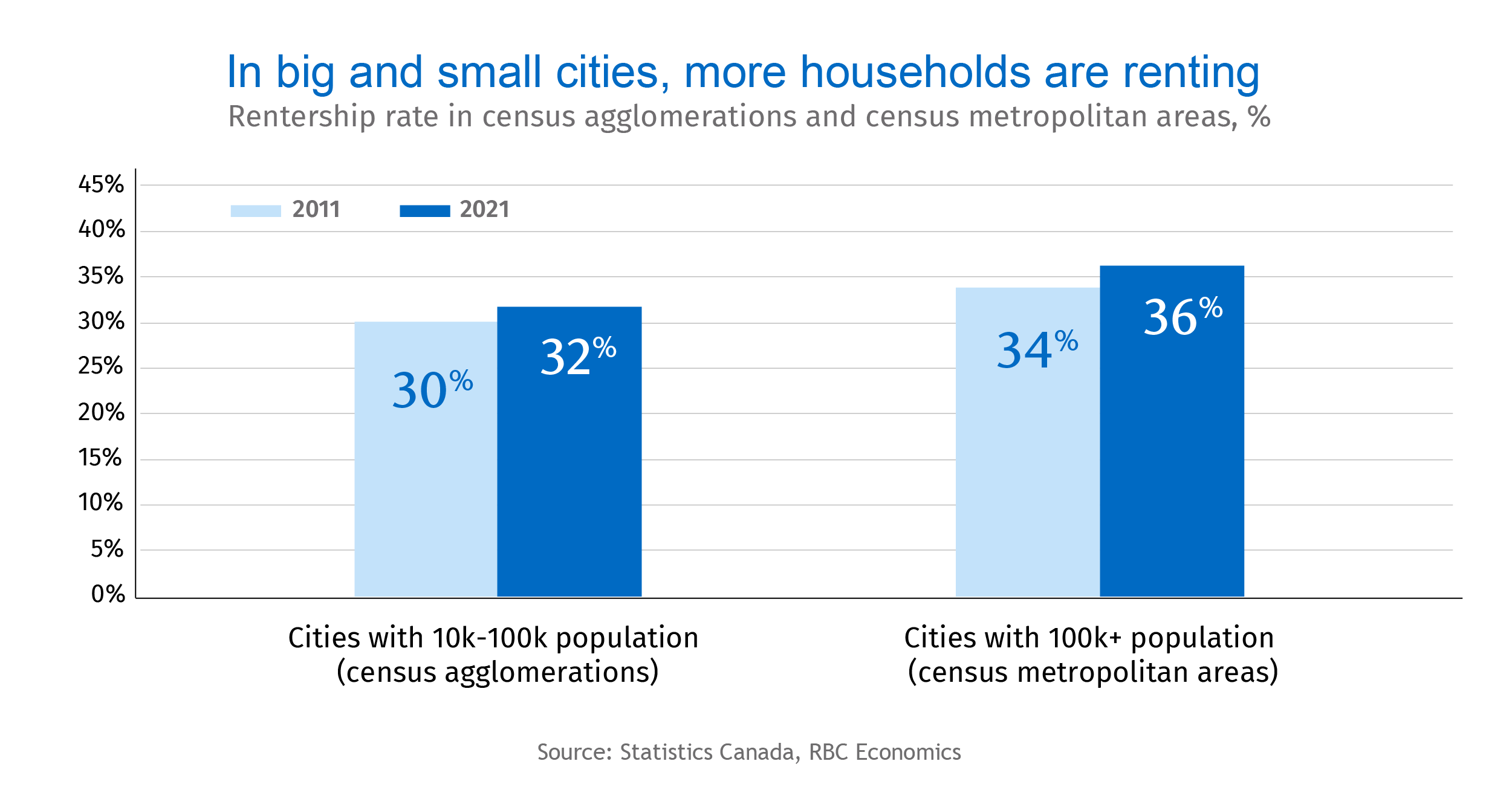

- Growth in rentership is now strongest among baby boomers and in smaller cities.

- The affordability pressures, demographic forces, and behavioural preferences currently driving this change will continue to fuel it in the years ahead.

- The bottom line: The rapid growth in renters isn’t about to slow down. Concerted efforts among policymakers, developers and builders are required to ensure, expand and diversify Canada’s stock of suitable, affordable, and stable rental housing.

The rise of the renters

There have never been so many renters in Canada. According to the 2021 Census, almost 5 million households rented the home they lived in last year—up from 4.1 million a decade earlier. And while owner households still dominate the Canadian landscape by a ratio of two-to-one, renters accounted for most of the growth over the past 10 years. Rentership increased by 876,000 households (or 22%) compared to a rise of 770,000 (8%) in owner households.

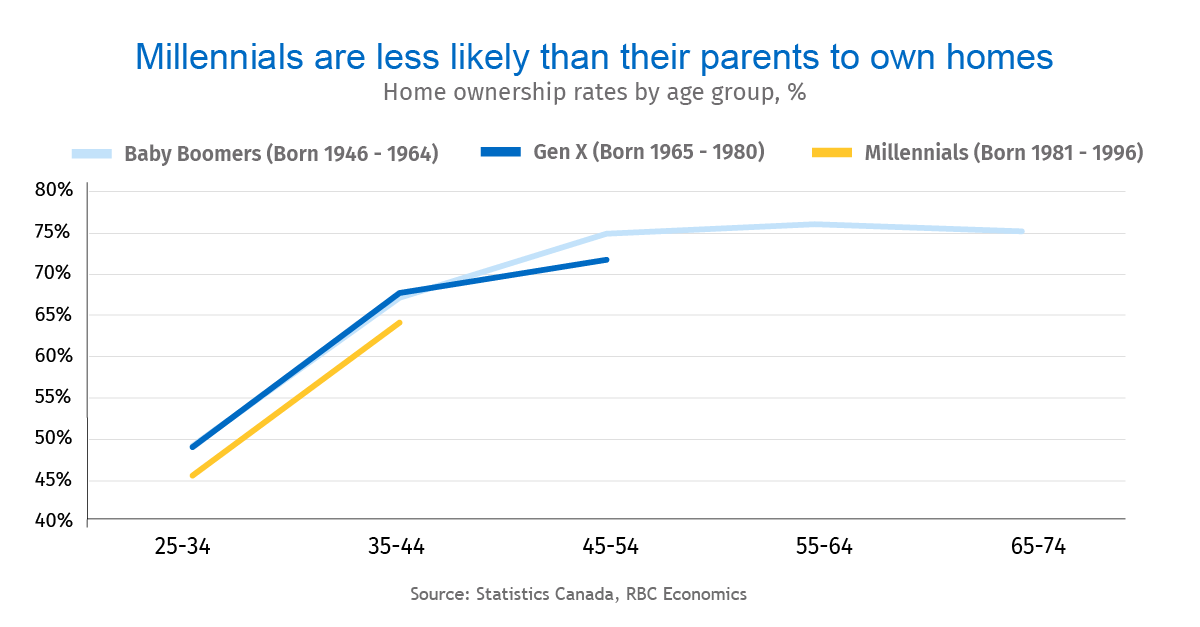

Millennials are renting for longer than previous generations

Renting used to be a swift rite of passage to buying a first home. But there’s ample evidence that younger generations of Canadians aren’t progressing up the housing ladder (from rental housing to starter homes to larger homes) quite so fast. Indeed, data suggests millennials’ ownership rates are lagging those of previous generations at the same age. And millennials are lingering in rentership three to five years longer than their baby boomer counterparts.

This isn’t necessarily by choice. Challenging affordability conditions are no doubt impeding millennials’ climb up the housing ladder—and especially their entry into home ownership. Despite many programs to help first-time homebuyers, the rate of home ownership (66% in 2021) is now trending lower and getting ever-closer to the OECD average (64%).

Enter the boomers: rentership not just a young, urban phenomenon

Cost pressures have historically made renting more common among younger age groups and urban households. But recent census data points to a broader shift over the last decade. Between 2011 and 2021, baby boomers (born 1946 to 1964, and the largest generation of Canadians) surpassed millennials (born 1981 to 1996) as the fastest growing group of renters (+4%). Additionally, the share of renter households has increased across municipalities of all sizes. At 22%, renter growth over the last ten years was slightly stronger in smaller cities (census agglomeration areas) than in larger cities (census metropolitan areas) at 21%. The widespread shift toward renting suggests affordability issues in large urban areas may not be the only driving force.

Demographic trends also fuel rental demand

Rising immigration and an aging population are also supporting rental demand. Given most newcomers typically rent for the first five to ten years of living in Canada, rapidly growing immigration targets (rising from 250,000 in 2011 to more than 401,000 in 2021) have significantly boosted demand for rental housing. Of the one million recent immigrants (a landed immigrant or permanent resident for five years or less) living in private dwellings, 56% (640,700) were living in rented accommodation in 2018. That’s nearly two-times the national average, leaving immigrants to represent a disproportionately high share of rental households in Canada.

Canada’s aging population has also bolstered demand. Of the 5 million tenant-occupied dwellings recorded in 2021, nearly a quarter (22%) were occupied by seniors aged 65+. That’s a 3 percentage-point increase from the 19% share reported in 2011.

And more Canadians are choosing to live alone. Since two incomes are often necessary to cover the high costs of ownership, many of these individuals end up renting. As of 2016, persons living alone overtook married couples as the most prominent household type, representing nearly 30% of all households in 2021.

We expect these demographic and behavioural trends to continue fueling demand for rental housing in the years ahead.

Wider array of rental housing needed

Burgeoning rentership will put tremendous pressure on our rental stock—already stretched and inadequate in many parts of the country. We’ll need to build more rental units. A lot more. And they’ll have to be the right kinds of units to meet the population’s increasingly diverse needs and income levels. This includes rental options suitable for families—that is, in neighborhoods close to schools and other amenities. The sharp rise in renter households living in single and semi-detached homes (+33%) over the last 10 years also speaks to a growing need for rental housing in lower density areas.

We believe addressing the so-called “missing middle” in some of Canada’s largest cities would go a long way toward broadening rental options. And as the federal and some provincial (e.g. Ontario) governments aim to double housing construction over the next decade, there’s a golden opportunity to do just that through the right mix of policies, regulatory changes and incentives.

Robert Hogue is responsible for providing analysis and forecasts on the Canadian housing market and provincial economies. Robert holds a Master’s degree in economics from Queen’s University and a Bachelor’s degree from Université de Montréal. He joined RBC in 2008.

Rachel Battaglia is an economist at RBC. She is a member of the Macro and Regional Analysis Group, providing analysis for the provincial macroeconomic outlook.

Proof Point is edited by Edited by Naomi Powell, Managing Editor of RBC Economics & Thought Leadership.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates. This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward- looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social- impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.