A big reason for this is that the skill sets that many immigrants bring to Canada and the study fields of international students do not match well with the anticipated longer-term structural needs of the economy. This impairs the prospects for newcomers and, more broadly, the economy.

Right now, the immigration system may be focusing too much on the labour market’s short-term demands, filling holes in sectors where low-skilled occupations have been experiencing acute shortages since the pandemic.

This has led to a surge in non-permanent residents, a strain on housing and social services, and eroded public support for immigration.

The federal government needs to update immigration policies to focus more strategically on immigrant outcomes and the long-term structural needs of the labour market, while keeping in mind the infrastructure capacity to accommodate newcomers. Addressing this will be key to maintaining economic prosperity over the long run, and Canada’s high quality of life.

This report will look at how a combination of a mismatch in immigrants’ skills and the labour market’s long-term needs, along with pressure on the country’s infrastructure capacity is leading to negative economic outcomes.

-

Expanding immigration targets to address an aging demographic and meet short-term labour market needs has led to a widening gap between workers’ skills and the abilities needed to address long-term structural labour shortages.

Expanding immigration targets to address an aging demographic and meet short-term labour market needs has led to a widening gap between workers’ skills and the abilities needed to address long-term structural labour shortages. -

Employment from temporary work permit holders including international students is concentrated in sectors with low-skilled occupations, which reduces the incentive for businesses to innovate and invest in labour-augmenting or -saving technology.

Employment from temporary work permit holders including international students is concentrated in sectors with low-skilled occupations, which reduces the incentive for businesses to innovate and invest in labour-augmenting or -saving technology. -

Canada’s two-step pathway to apply for permanent residency needs greater oversight to ensure the system isn’t being abused by educational institutions and applicants.

Canada’s two-step pathway to apply for permanent residency needs greater oversight to ensure the system isn’t being abused by educational institutions and applicants. -

The stress on infrastructure and social services needs to be addressed to improve economic outcomes for immigrants and their surrounding communities.

The stress on infrastructure and social services needs to be addressed to improve economic outcomes for immigrants and their surrounding communities. -

Canada’s Comprehensive Ranking System needs to be updated to prioritize economic immigrants with higher predicted earnings.

Canada’s Comprehensive Ranking System needs to be updated to prioritize economic immigrants with higher predicted earnings.

Growing the ranks of working-age people who have higher earning potential will be crucial to help spread the costs of social support programs such as healthcare. But policymakers also need to meet the challenges of integrating a large and growing number of new immigrants over the medium term.

Expanding immigration targets

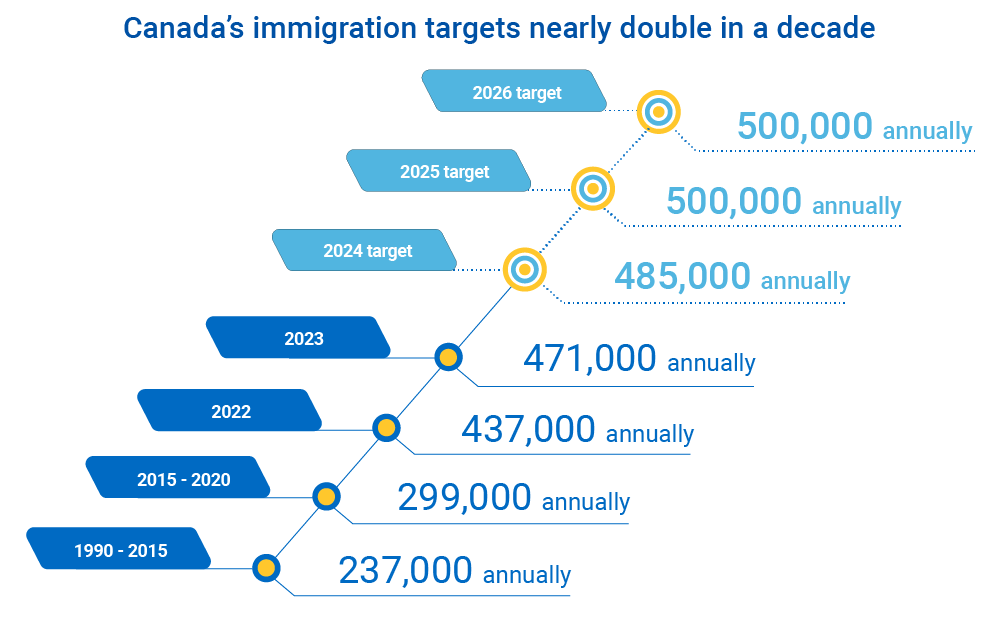

The push by the federal government to increase immigration to offset the impact of an aging demographic has been successful in strengthening the labour force in the near term.

Canada’s population grew by a substantial 3.3% in the 12 months to July 2023—the highest rate in more than six decades. The rise was driven almost entirely by in-migration as the federal government raised immigration targets for permanent residents.

A steady stream of immigrants is needed as more than 500,000 Canadian baby boomers hit retirement age—65—annually. Natural population growth is falling to the point where by 2030, overall population growth is expected to be fueled entirely by immigration.

Meeting short-term labour market needs

The labour force surged 6.8% in the past three years—growth unseen since the early 2000s. More international students are earning money while studying than ever before. In 2000, about one in five had a job. Today, about half are working while studying. Employers were able to tap into a pool of an estimated 1.2 million temporary residents with work permits in fiscal 2022-23. The federal government also made available one-time 18-month extensions in 2023 to people working under post-graduation work permits (PGWP) to further address broad-based labour shortages.

It reduces the incentive for Canadian businesses to innovate and invest in labour-augmenting or -saving technology needed to deal with an aging demographic and keep the economy globally competitive.1 The current economic weakness may also have a significant impact on low-skilled occupations with non-permanent residents and recent immigrants likely to disproportionately bear the brunt of job losses.

Mismatch between skills and labour market needs

The longer-term benefits of the abundantly available labour are also not clear as shortages in multiple fields, primarily healthcare and skilled trades, remain significant despite the increase of workers.

Almost half (46%) of projected structural labour shortages are in occupations that don’t require a university or college education. That indicates the skill sets that international students are studying do not match well with the anticipated longer-term structural needs of the jobs market.

International students at colleges and universities are overrepresented in business management and STEM fields and underrepresented in the skilled trades and healthcare. While some healthcare and skilled trade workers from other countries obtain temporary work permits and professional licenses, they represent a disproportionately small number of employed temporary residents.

The role of Canada’s ‘two-step’ immigration system

Canada’s immigration system is heavily reliant on its “two-step” immigration program that allows international students to eventually apply for permanent residency.

In 2018, almost 60% of economic stream immigration applicants had Canadian work experience, indicating that the majority of permanent immigrants were drawn from the pool of temporary residents.ii Strains on infrastructure and the changing labour market suggest Canada needs to broaden the potential ways for newcomers to immigrate.

Graduation from designated schools automatically qualifies international students for a PGWP, allowing them to gain valuable work experience and better qualify for permanent residency.

The two-step pathway also suits post-secondary institutions, including many contending with a funding squeeze amid flat real provincial funding and declining or frozen domestic student tuition fees. Many universities and colleges rely on the higher tuition fees from international students to cover funding gaps—even though students from other countries represent less than a fifth of university enrolments in Canada. Still, they account for a third of tuition fees.

There’s been a particular emphasis on cracking down on “puppy mill” schools—for-profit private career colleges and similar institutions that the government has deemed as not offering a legitimate student experience while churning out diplomas. Private colleges, some in partnership with public colleges, have increasingly targeted international students as a lucrative source of revenue. This has led to negative outcomes for students and their surrounding communities.

Strain on housing and social services

Housing is a key challenge with demand disproportionately affecting Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal—high-priced markets with low housing supply.iii Policy measures have been introduced to accelerate home building including a federal GST rebate on new purpose-built rental construction, but the

The squeeze on social infrastructure is no different. Immigration is an important part of the solution for bringing in trained staff for jobs in social services, but even the best candidates often struggle to integrate seamlessly. Training and hiring additional educators, hospital staff, or community support workers also takes time.

Government response to the challenges

A series of changes and updates have been announced by the federal government in an attempt to reel in a ballooning non-permanent resident population and regain greater oversight into newcomers entering the labour market.

In January, the federal government implemented a cap on the total study permits to be issued over two years—limiting it to 364,000—roughly half the number of permits issued in 2023.

The government also implemented stricter financial requirements for foreign students applying, upping the minimum capital requirement from $10,000 to more than $20,000 to ensure students have enough of a cushion to support their needs while studying. Work visas for spouses of undergraduate international students will also no longer be issued, and students studying at private colleges will no longer be eligible for the PGWP in an attempt to address potential loopholes in the system.

However, the government will have to go beyond these initial steps to update the immigration system in order to ensure both the economy and newcomers can once again prosper from the benefits of immigration.

Policymakers should examine other streams of non-permanent residents—like the Temporary Foreign Worker and International Mobility Programs—where numbers have also ballooned. They must address housing shortages on and surrounding campuses and update the selection process for permanent residents by streamlining the number of pathways available to prioritize candidates with the highest predicted earnings.

Here are recommendations that could help keep the immigration system on track to meet the country’s needs

The current CRS, developed in 2015, has selection criteria focusing on factors that include language proficiency, age, and education level. Applicants are, periodically, invited to apply for permanent residency based on a set ranking score cutoff. Higher immigration targets have meant reaching deeper into the pool of applicants to meet those targets. The cutoff scores have been lowered in order for more permanent residents to be selected from the process.

The CRS should be updated and streamlined to prioritize economic immigrants with the highest level of predicted earnings. Focusing on higher-earning immigrants can help improve economic outcomes for newcomers as well as encourage businesses to innovate or make labour-augmenting investments to overcome the shortage of low-skilled workers.

Universities and colleges should do more to provide work opportunities and increase job readiness for international students. Federal policy needs to remove or alter the requirement that international students state they do not intend to remain in Canada after graduation. Prospective students must indicate they do not intend to stay beyond their study permit, even though programs like the PGWP are designed for them to do so. This would help post-secondary institutions better create school-work pathways for international students. In addition, education for employers on the rules and benefits of hiring international students needs to be improved.

More labour market and language experience during studying would help temporary residents gain permanent residency faster and improve their prospective post-immigration earnings. International students are currently excluded from many work-integrated learning opportunities.

Credential recognition has been a long-standing issue for newcomers. For high-earning professional designations, the certification process of immigrant credentials can be lengthy and costly. There aren’t clear frameworks for other professions, and it is often left to employers to determine the suitability of a newcomer candidate. This can be a time-consuming process for employers and a barrier to finding meaningful employment for immigrants.

For more, go to rbc.com/thoughtleadership.

Download the Report

Contributors:

Benjamin Richardson, Researcher

Cynthia Leach, Assistant Chief Economist

Rajeshni Naidu-Ghelani, Managing Editor

Related Reading

- ihttps://clef.uwaterloo.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/CLEF-058-2023.pdf

- iihttps://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-626-x/11-626-x2020010-eng.htm

- iiihttps://www.bankofcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/san2021-21.pdf

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates. This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward- looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social- impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.