There is a circle to be squared in what’s happening in the Canadian economy with two contradictory trends that both appear to be true.

First, on the whole, Canadian household balance sheets have never looked stronger. Households in aggregate are sitting on record levels of savings. But under the surface, there are clear signs that the average Canadian consumer is suffering. Delinquency rates are rising, demand for services like food banks is at record levels, and per-capita household spending is falling like the economy is in recession.

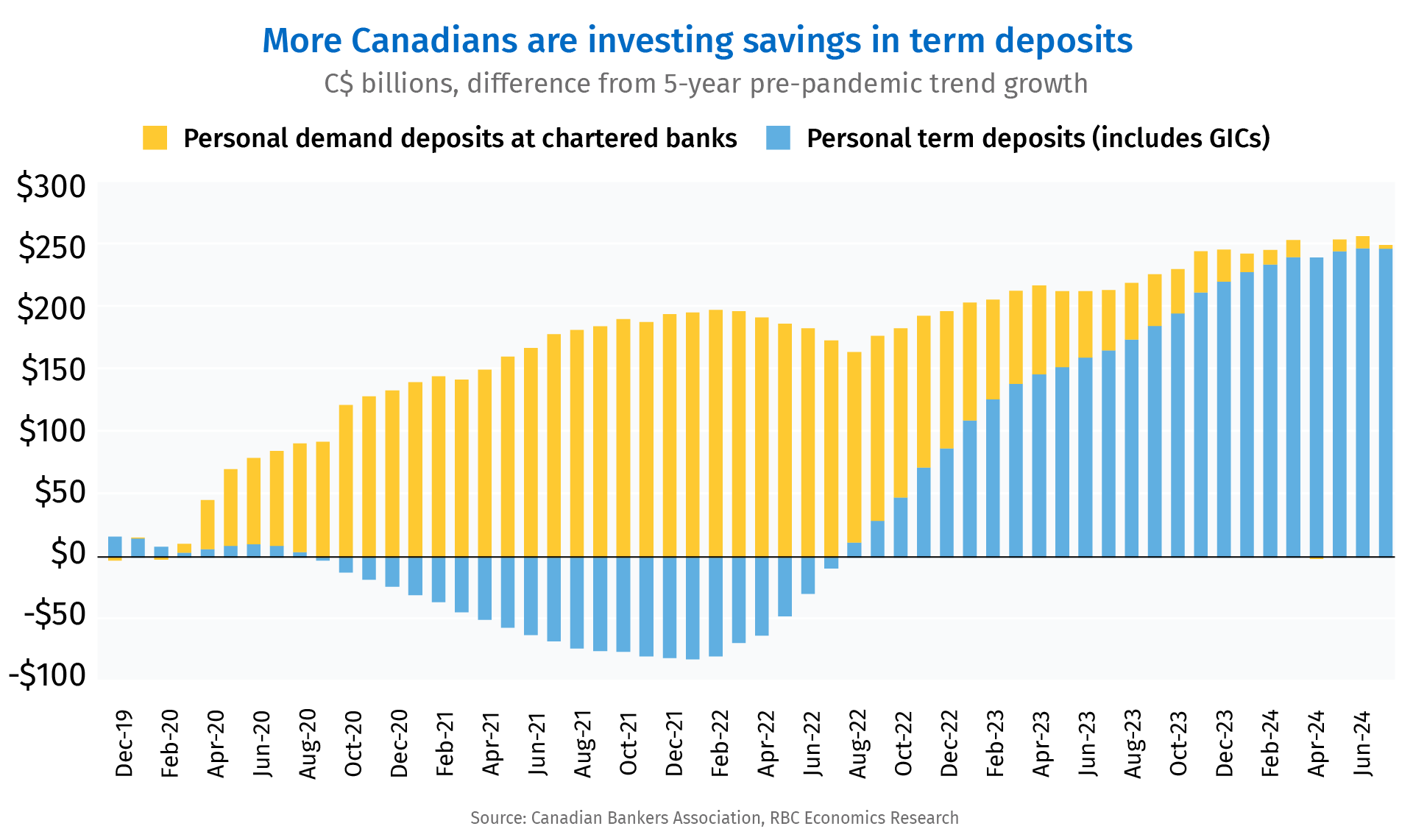

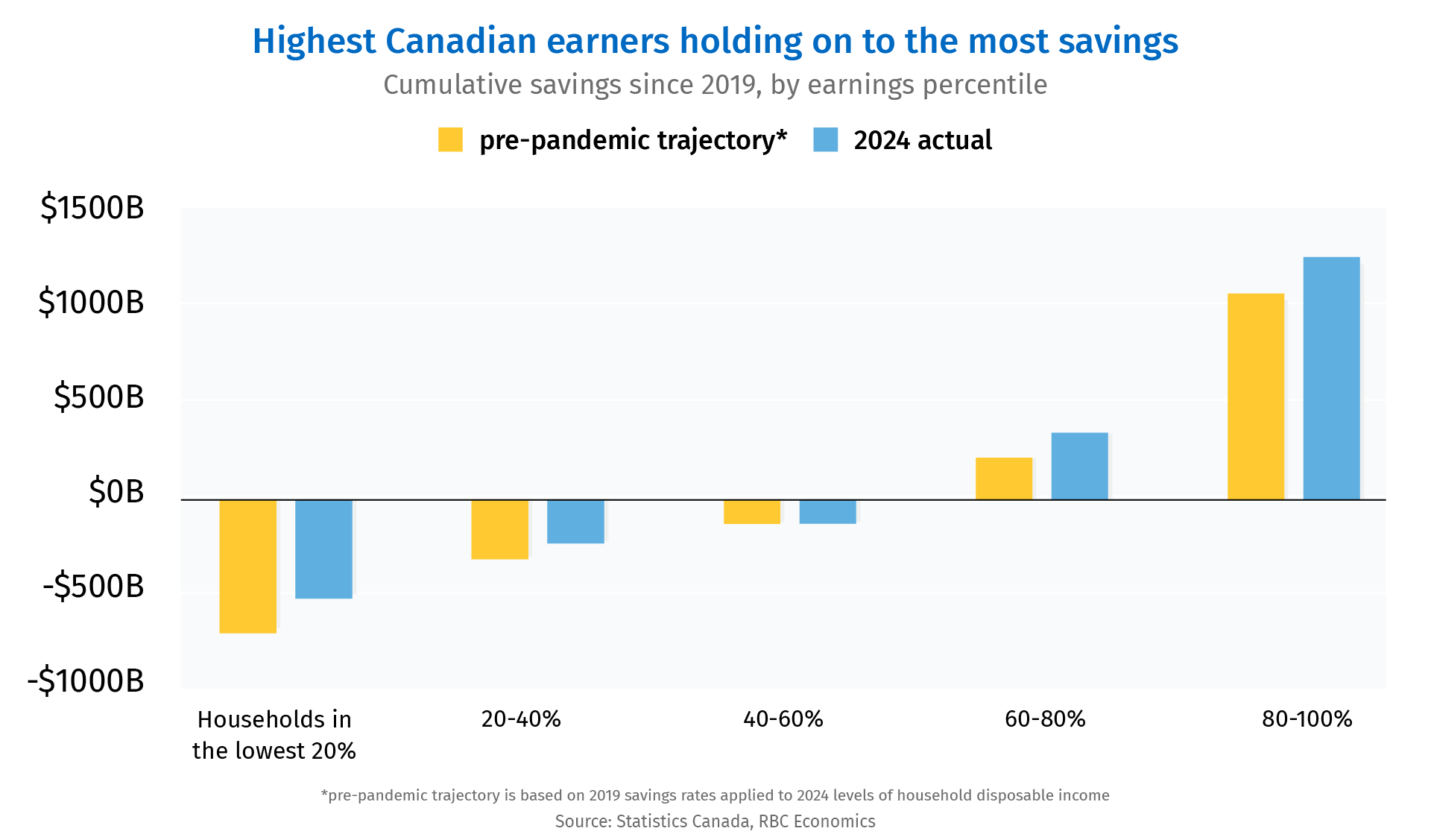

The missing piece connecting these two facts is that the accumulation of household savings has not been evenly distributed. The top end of the income spectrum has been doing fine. Indeed, there has been a dramatic shift to term deposits for household savings that are not needed immediately and aren’t likely to be spent quickly. Meanwhile, higher interest rates, prices, and a rising unemployment rate are cutting into the purchasing power of lower-income groups.

Low and middle-income earners getting squeezed

Canada’s lowest-income earners have always devoted the greatest share of their take-home pay to essentials like shelter, utilities, groceries, and transportation. Those in the bottom 20% of income earners are going into debt to purchase essentials.

This group had a reprieve during the pandemic when government transfers to households made up for lost earnings. But now, they are back to where they were in 2019 with essentials accounting for 105% of their household disposable income.

Middle-income earners (those in the 40% to 60% of income distribution) have also become exceptionally stretched. In 2023, they devoted the greatest share of their take-home pay to essentials since 1999. They have spent 17% more than their take-home pay in 2024, implying “dis-savings.” That compares to a 9% dis-savings rate in 2019. This group has completely depleted “excess” pandemic savings squeezed by higher mortgage payments and higher costs for essential goods.

Highest earners build on savings

Canada’s highest-income earners (top 20%), on the other hand, are collectively amassing significant levels of savings. They are saving roughly one-third of their take-home pay each quarter. They are the only group that has not seen a material pullback in pandemic savings since 2020. The country’s top 40% of earners have accounted for 60% of the appreciation in financial assets since 2019. This explains why household deposits have risen significantly while food banks struggle to meet demand.

Hit by rising prices and the jobs market

The after-effects of decades-high inflation continue to hurt Canada’s low-income earners. Inflation has returned to the Bank of Canada’s 2% target and wage growth has just eclipsed price growth—meaning average wage levels relative to 2019 have surpassed inflation. But, this does not adequately capture how inflation “feels” to Canadian households. A greater share of total spending by lower-income earners is going to essentials, which reported the highest price growth during the pandemic recovery. Grocery prices have risen 25% from before the pandemic, while gasoline prices have risen 33%.

Added to this, Canada’s lowest income earners have been most vulnerable to job losses as openings have fallen below the number of job seekers. The middle class has also reported the weakest growth in household disposable income. Their average wage growth is up only 3.7% over three years, compared to 13% growth for the highest earners. This group did not benefit from significant government transfers like the lowest earners did, but they also didn’t fare as well as Canada’s high earners. The top 40% of income earners have accounted for 70% of wage growth over the past three years.

The Bank of Canada aims to promote the financial well-being of all Canadians, but an uneven recovery makes their mission exceptionally difficult. Higher interest rates increase the cost of borrowing, cooling demand, and, in turn, exert downward pressure on inflation. But, higher interest rates also translate to higher returns on investments and savings for Canada’s wealthiest—creating a more pronounced income disparity among all households.

Carrie Freestone is a member of the macroeconomic analysis group and is responsible for examining key economic trends including consumer spending, labour markets, GDP, and inflation.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates. This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward- looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social- impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.