Green Collar Jobs is the latest report in RBC Economics and Thought Leadership’s climate series, building from the team’s flagship report, The $2 Trillion Transition, which was launched in October 2021. This climate series is designed to inform and inspire Canadian prosperity, while advancing RBC’s ongoing commitment to speak up for smart climate solutions, a key pillar of RBC’s Climate Blueprint.

Key findings

3.1 million Canadian jobs—or 15% of the labour force—will be disrupted over the next 10 years as the country transitions toward a Net Zero economy.

8 of 10 major economic sectors will be affected as the workforce adapts.

Canada’s transportation, energy and manufacturing sectors will undergo the most significant early shifts, as 46% of new jobs in natural resources and agriculture and 40% of new jobs in trades, transport, and equipment require an enhanced skillset.

Initial changes will affect highly-paid, highly-skilled workers more dramatically. Managers in engineering, architecture, utilities and manufacturing are already seeing over 50% of their tasks shift due to the climate transition—five times that of managers on average.

For workers, upskilling could also bring significant opportunities. Between 235,000 to 400,000 new jobs will be added in fields where enhanced skills will be critical.

A highly-skilled Net Zero workforce could establish Canada as a top destination for green investment, building on existing advantages, including a free trade pact with the U.S. and Mexico and large deposits of natural resources critical to clean technology.

A comprehensive skills strategy must be a key pillar of Canada’s $2 trillion Net Zero transition, particularly as other countries compete for investment.

Why skills are the key to green economic growth

Canada is on the cusp of a generational skills crisis. As a nation, we’ve set some of the most ambitious climate objectives in the world, led by an overarching goal to reach Net Zero emissions by 2050. This pursuit brings with it an abundance of opportunity: for Canadian innovation, for new green investment, and for economic growth.

But none of it will happen without people. Our journey to Net Zero hinges not just on the large-scale mobilization of financial capital but also, critically, human capital. According to our research, 3.1 million Canadian jobs will change in some way over the next decade due to the climate transition. Traditional energy sector workers will need to be bridged to new, growing areas of the economy as this evolution plays out. But as our research shows, equally important and wide-ranging skills shifts are already taking place in other parts of the economy.

Companies like Vancouver’s Ballard Power Systems, at the forefront of the energy transition, will need engineers trained in the rapidly-evolving technology of hydrogen fuel cells. Long-established industrial giants like Sault Ste. Marie’s Algoma Steel will need to recruit and retrain workers as it overhauls its operations to rely on clean electricity. Firms like Oakville-based Samuel, Son & Co.—one of the largest North American metals processors, now pivoting to automation, robotics and innovative new forms of manufacturing—will increasingly seek engineers, workers with hybrid skillsets and those with training in new disciplines like mechatronics (integrating mechanical, electronic and electrical engineering), as it aims to make supply chains more efficient. And nearly everywhere, across nearly every industry, Canadian companies will need more traditional skilled tradespeople—the metallurgists, welders, machinists and other workers already in severe short supply.

To meet the moment, Canada needs a strategy—and a workforce nimble enough to keep pace with the rapid technological and operational changes driving the climate transition. We’ll need new models of collaboration among businesses, government and post-secondary institutions. We’ll need companies driving cutting-edge innovation to take a bigger role in work-integrated learning and training. And we’ll need workers and students to adopt a mindset of constant learning. Chronic problems will have to be tackled too, including longstanding bottlenecks in our pipeline of skilled tradespeople and a failure to tap into underutilized pools of talent such as women, immigrants and Indigenous youth.

Skills must be at the heart of any strategy to achieve Canada’s new target of cutting emissions by at least 40% by 2030. Yet so far, our discussions have been largely limited to debate about regulation and technology.

In this report, we examine the transformations already underway in Canada’s labour force as the country moves to a Net Zero economy. We map out the sectors and occupations experiencing the greatest disruption, the ways skills are shifting within specific professions and the competitive advantage that a green workforce will bring. The challenge ahead is sizeable, but for workers and employers alike, the payoff could be significant: as many as 400,000 new jobs will be added in fields that will demand enhanced skills. The importance of these green skills can’t be overstated—equipping Canadians with them is the only way to get to Net Zero.

1. New skills at green companies (“Jobs with enhanced skills”)

These are workers who must learn new skills to work at firms developing technologies that will help accelerate transition to a Net Zero economy.

Challenge: On-the-job and work–integrated learning for proprietary technology

Example: Fuel cell engineers

2. Existing skills at green companies (Not included directly in our analysis)

These Canadians work for the companies facilitating transition, but in occupations that are mostly insulated from skills and task changes.

Challenge: Attracting talent to new sectors to help them scale

Example: Human resources at a solar panel manufacturer

3. Increasing demand for existing skills (“Increased demand”)

These workers already have the requisite skills for new tasks, so need little additional training, but we’ll need more workers in these areas.

Challenge: Encouraging more Canadians to choose these fields

Example: Electricians upgrading service to buildings across the nation to accommodate electric heating, appliances, and vehicles

4. New skills in existing jobs (“Jobs with enhanced skills”)

These workers’ jobs are changing, even as their industries or employers don’t.

Challenge: Upskilling existing workers as their jobs change

Example: Welders joining steel and aluminum to build EVs

Mapping the green skills challenge

The pandemic shook Canada’s workforce, delaying retirements, prompting a wave of job switching and drawing attention to longstanding chokepoints in the pipeline of skilled tradespeople. Employment is above pre-pandemic levels, and tight conditions in certain industries have pushed job vacancies to record highs of nearly 1 million. And shortages of skilled tradespeople critical to manufacturing, construction and other sectors are poised to grow even more severe in the next five years, according to our research.

Now, a failure to get enough Canadians with the right green skills into the labour force could further limit our growth potential. As early as 2025, the country could be short roughly 27,000

environmental workers, a category that includes those employed by green firms or engaged in green tasks.1 That shortfall will be more painful in some sectors than others. For instance, Canada will be short about 7,500 senior managers and 7,300 engineers and physical scientists as demand for these skills soars. As clean electricity grows as a key source of energy, workers with electrical skills will be highly sought after. Overall, by 2030, 98,000 new positions will be created in jobs where skills won’t change but will be in increased demand due to the climate transition.

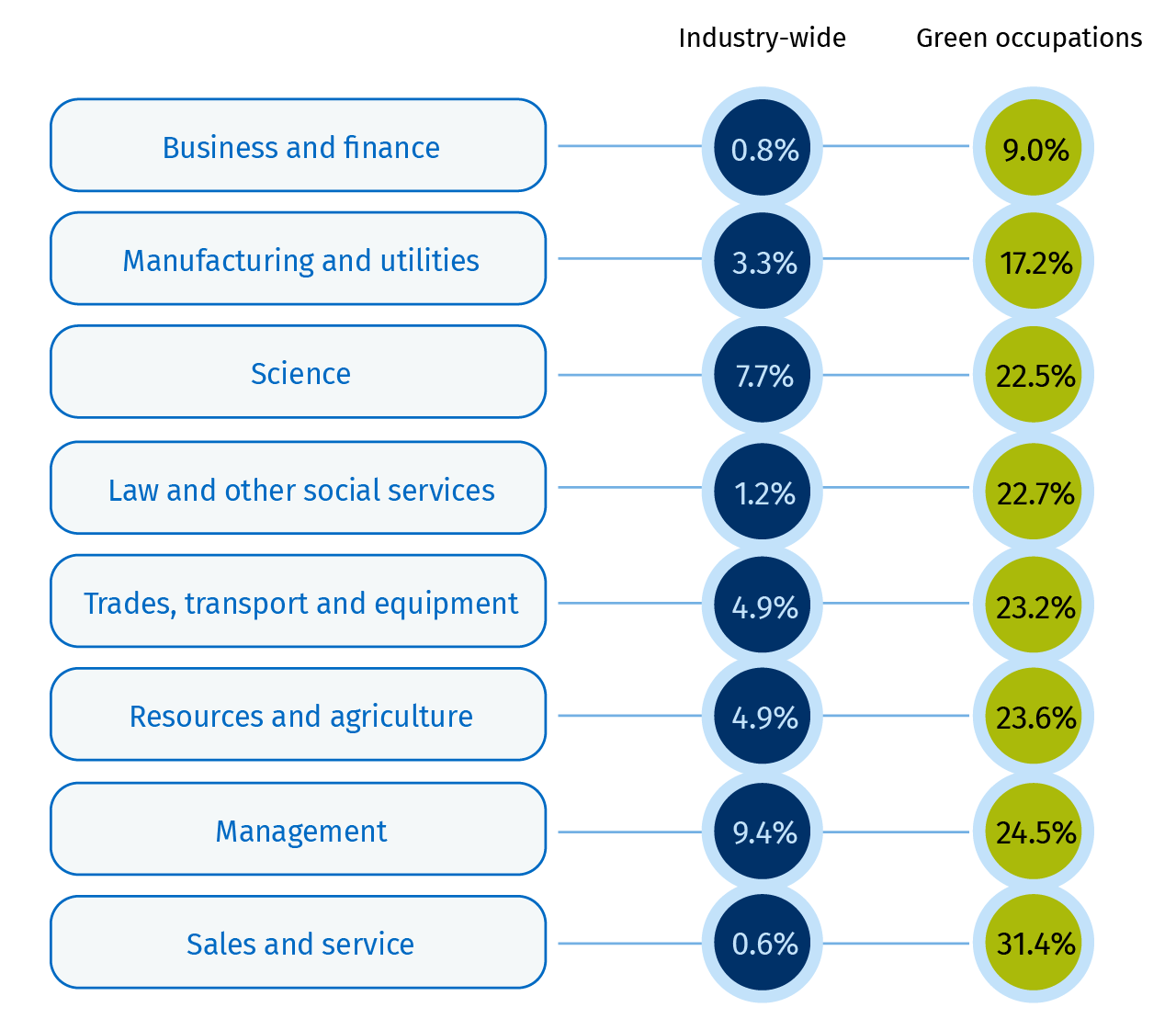

Beyond tightening the current labour squeeze, the Net Zero transition will demand a reshaping and enhancing of existing skillsets. Accountants will need to audit emissions as well as financial statements, and city planners will be tasked with designing urban settings resistant to the impacts of more frequent floods and wildfires. The overall shift in many occupation groups may be small, but for some jobs, an average 25% to 30% of tasks are already changing.

By 2030, roughly 235,000 or 13% of new positions will be in occupations where descriptions are changing due to the Net Zero transition. That could rise to as much as 20%, or 400,000 positions, if growth in clean transportation and industry follows the trends expected by Clean Energy Canada, a Vancouver-based think tank.2 And even faster growth for green skills in construction and trades is possible if Canada closes the spending gap, investing an additional $60 billion needed annually to reach our climate targets, starting with major carbon capture and green infrastructure projects.

In certain occupations, the skills shift is already significant

Share of green tasks

Source: RBC Economics

Occupational breakdown: Existing vs green tasks

How climate is disrupting supply chains—and workers

Transportation has been at the forefront of accelerating demand for green technologies. Early government action on climate change has focused heavily on incentives for electric vehicle adoption and production. But EVs come with a set of requirements distinct from those of gas-powered vehicles. For one thing, they need lighter, stronger materials to improve efficiency. And increasingly, automakers focused on cutting emissions from their production and supply chains are demanding the cleanest possible inputs. This single point of demand—from one of North America’s most important industries—is catalyzing operational and skills transformations through an entire supply network. Climate action is not only changing what we make, but how we make it.

In some cases, the workers experiencing the biggest changes will be those directing the transition. Specialized managers planning for new production processes in engineering, architecture, utilities and manufacturing are already experiencing a shift in over 50% of their tasks. Some task changes won’t require major retraining, but others will.

At Algoma Steel, managing change has become one of the company’s biggest challenges. To decarbonize its steel—and capture more of a rapidly greening automotive market—Algoma will invest $700 million into electrifying its processes. Electric arc furnace steelmaking, which uses high-current arcs to melt scrap into liquid steel, will replace the coal-fired basic oxygen method in a shift expected to play out over a decade and cut emissions by 70%. Despite the scale of this operational shift, most job descriptions won’t change, and others won’t change right away. Workers handling hot steel, for instance, will continue to do just that, regardless of the production process. But some staff, particularly those focused on the specific needs of the electric arc method, such as procuring scrap metal and managing a significantly larger electricity supply, will need to upgrade their skills as their roles grow in importance.

“Automakers are looking for a partner in business that can sustain them across the cycle. As the carbon content and price of carbon factors its way into the supply chain, they want to know they’re working with a partner that is stepping up to address that.”

– Michael McQuade, CEO, Algoma Steel

Algoma Steel

Traditional steelmaking is among the heaviest carbon emitting processes in the global economy, accounting for 8% of total global CO2 emissions. Betting that the ultimate cost of carbon will drive a significant portion of the market to seek alternatives, Algoma Steel is embarking on a $700 million project to convert the entirety of its operation to electric arc furnace steelmaking, in which scrap metal is melted and recycled. The move will cut emissions by 70% as the main source of fuel shifts from coking coal to green hydroelectricity.

To make it happen, Algoma will need to reallocate workers from blast furnaces to electric arc furnaces. This will require a degree of retraining for workers, but many of their skills will remain relevant and applicable to their new responsibilities. Some of the biggest changes for the company are expected to be in administrative and managerial roles. Procurement people already have some experience in scrap markets, but the magnitude of what’s needed in the operation will substantially change, as will the importance of the purity of that scrap. What’s more, as the company doubles its draw of electricity to 300 megawatts—the size of an average natural gas power plant—it will need to increase the proportion of staff with expertise in handling high voltages.

Algoma expects automation and technology to present the single biggest skills challenge to its operations in the future.

“Looking forward, the skills required by future generations of steelworkers are going to be dramatically different, incorporating technology. And that’s anywhere from robotics to artificial intelligence in a manufacturing environment like our own.”

– Michael McQuade, CEO, Algoma Steel

Further down the value chain, the need for lightweight materials means aluminum is becoming a metal of choice for EVs. That’s increased the complexity of making these vehicles since welders need special skills to join multiple metals together. As our previous research revealed, this trade is already facing some of the most severe shortages. But technological shifts, including those driven by the green transition, are also altering the tasks welders must perform. This is also true for industrial mechanics and many other positions with significant technical skills. Some 40% of new jobs in the trades, transport, and equipment occupations will need an enhanced skill set, according to our findings. Vaughan-based auto parts manufacturer Martinrea International has responded by doing more of its training in-house—where most of its innovation takes place—while leaning on post-secondary institutions to provide core skills.

“We look for people educated in mechatronics and robotics, and we look for material engineers. But after that, we don’t send our people offsite to learn, it mostly happens on the shop floor.”

– Rob Wildeboer, Executive Chairman and Co-Founder, Martinrea International

Bigger changes are yet to come: added focus on sustainability has already begun to shift attention to new kinds of manufacturing focused on leaner supply chains and less waste. The market for so-called “additive manufacturing,” which utilizes 3D printing, is expected to triple to US$37 billion by 2026. For Samuel, Son & Co., a North American leader in the field, the challenge to growth rests in getting engineers who can think differently about how to manufacture metal components for use in aerospace and other highly technical applications. Roughly 30% of occupational tasks are changing for engineers more broadly, in sectors including aerospace, transportation, mining and civil planning.

“Now we’re literally taking people out of university who don’t have too many preconceived ideas around manufacturing and design… so they can figure out how to design from first principles.”

– Colin Osborne, CEO, Samuel, Son & Co.

Samuel, Son & Co

Automakers are increasingly seeking different materials, such as lighter weight aluminum blanks critical to the design of electric vehicles. This has required a certain degree of retraining and shifting skills on the shop floor. But for fabricating companies, one of the biggest challenges is securing talent in a market where labour is not only scarce but in some cases completely unavailable. Samuel, Son & Co has gone to extremes to find shop-floor talent, in some cases unbolting machinery and moving it among its 100 locations to where the talent is. Labour availability is now a “gating criteria,” key to its decisions about where to establish new locations.

But looking forward, the skills of that labour force are set to become a gating criteria of their own. The market for additive manufacturing, where 3D printing has the potential to shorten supply chains and improve their sustainability, is expected to double to US$37 billion in 2026 globally. Given innovation in this nascent industry is almost entirely occurring within the companies themselves, the critical skills engineers need to work in the field are largely being taught by employers. Samuel invests heavily in new graduates to equip them with the skills needed for this new type of manufacturing.

“Three years ago…, I could advertise, I could get 10 welders. I could pick the top three welders, and that would be great. Now there’s no hope, I’m just not going to get one.”

– Colin Osborne, CEO, Samuel, Son & Co.l

Why employers must lead

Inherent in the skills challenge underpinning the Net Zero transition is uncertainty: about the pace and direction of technological change and the course of public policy. By extension, there remains uncertainty about how quickly Canadian workers will need to acquire new skills. Much will depend on which nascent technologies “win” or move into common use as others fail to thrive. Government policy will influence this race. Still, one thing is clear: as policies and technologies change, Canadian workers must be agile enough to respond. Workers will need to adopt a mindset of constant learning and upskilling, and employers will become more important than ever in training the workers of the future.

The most significant changes will come as we transform the energy sector to include more electricity, hydrogen and other solutions. Much like our current energy system, a cleaner one will have many location-specific elements. For example, we’ll position solar and wind farms where the sun is brightest and the wind is strongest. That means

Canadian workers will need to be mobile. To ease that mobility, provinces will need to remove barriers, including those that prevent the recognition of certifications.3

Smoothing the transition for energy sector workers

Few areas of the labour force will be transformed more profoundly by climate change than the energy sector.

The transition will be uneven: while all signs point to rapid growth in the electricity sector, the outlook for oil and gas is less clear. Domestically, fossil fuel use will fall as we switch to EVs and heat pumps, but global demand may change at a slower clip. And new technologies like carbon capture could enable us to continue using oil and gas for some time without damaging the atmosphere.

Those developments could temper the impact on workers and reduce the urgency for a labour transition plan. But we can’t wait forever: a strategy that fails to anticipate change and prepare workers in the most disrupted industries risks eroding support for broad climate action. And policies that create unemployment among some 80,000 oil and gas sector workers could damage the local economies they support, heightening regional tensions.

We have some time to develop a strategy since near-term demand for fossil fuels will continue to be robust. And we have options: a recent Conference Board of Canada study found that there are many transition pathways from disrupted to growing sectors. Nearly all workers can move into new roles with minimal wage disruptions after a year of retraining. Still, transition will be hardest for some mining, oil and gas workers: the major retraining they need costs more than $150,000. Should most workers in this sector need new jobs, we’ll need a strategy that helps cover those costs.

For now, Canada is in the planning phase—studying how these transitions could play out, where disrupted workers will go, and how to fund training. When the future of Canada’s energy sector becomes clearer, we’ll need to move from planning to practice. Laying the foundation for that shift today, and helping those eager to start retraining, will smooth out bumps on the path to transition.

Some bigger actors will be able to build bespoke in-house training programs. Ballard, for instance, appointed a Chief Learning Officer and is exploring how it can use social media platforms like LinkedIn to upskill employees. But smaller Canadian firms will need support to invest in their workers.

On-the-job training will also be increasingly important for young workers, given the rapid pace of technology development. Companies will design more proprietary technologies and processes to help cut emissions, from hydrogen fuel cells to additive manufacturing. That means more businesses will need to focus on hiring workers with core competencies and then investing heavily to equip them with bespoke skills.

But too much focus on employer-specific training has disadvantages, too. Finding the right electrician will be a challenge if every solar panel requires slightly different skills to install it, creating major inefficiencies. Industry organizations, firms, colleges and universities will need to work together to standardize training around widely accepted technologies, and firms will need to standardize the technologies themselves as much as possible.

These groups will also have to develop programs to create new, hybrid credentials. For example, roofers with enough electrical know-how to install solar panels, or household electricians with the skillset to install EV charging stations. Electricity HR, an Ottawa-based non-profit supporting the workforce needs of the industry, is developing national occupational standards for such skills, with an eye to developing micro-credentialing programs at post-secondary institutions.

Such a system could enable the layering of competencies and the development of skillsets tailored to the Net Zero economy.

All of this will require a sharpened focus and more investment. Canada has kept pace with peer economies in setting ambitious climate goals and funding green projects like Algoma’s transformation and efforts to accelerate carbon capture. But so far, skills development has not been a pillar of our climate transition strategy. By comparison, the U.K. has incorporated job market planning and skills development into its Ten Point Plan (TPP) and Net Zero Strategy and set an ambitious goal of creating 2 million green jobs by 2030.

“The predictions I’m seeing are that two to three times more generation capacity will be required. So I think by 2030, our workforce will probably be two to two and a half times bigger than it is today. It has to be because we have to build.”

– Mark Chapeskie, Vice President Program Development, Electricity HR

School’s In: The role of post-secondary institutions

For workers in the new economy, learning won’t end at the school gates.

The skills needed to work in the new economy will change as rapidly as the underlying technologies that cut emissions. That means post-secondary institutions will need to do more than equip students with human skills; they’ll also need to instill them with an ability to constantly learn.

At Southern Alberta Institute of Technology (SAIT), advanced manufacturing students participate in hackathons to develop these skills, and apply them in capstone courses where they work on real-life problems with industry clients.

Schools also lack the funding to constantly upgrade facilities to keep up with emerging technologies. So they’ll need close and dynamic relationships with private sector companies, especially those taking a leading role in developing technology in real-time. Simon Fraser University is developing a lab with Ballard along these lines.

Accountants are increasingly being asked to audit not just financial statements, but also the credibility of companies’ climate plans. That will demand that CPAs have a deep understanding of climate change. Training professionals will mean proactively developing curricula that reflect the growing importance of climate change as a business issue, as well as a societal one.

Recommendations: Seven Ways to build a Net Zero skills strategy

Make skills a central component of Canada’s Net Zero strategy. This will require Ottawa and the provinces to form an expert group to collaborate on funding, skills certification and labour mobility issues.

Map out Canada’s green skills gaps and opportunities. This will require Employment and Social Development Canada to collect, analyze and publish data on the underlying skills shift and projected employment in the Net Zero economy. Currently, Canada lags behind other countries like France that have national observatories to monitor the job transition. Robust information about how our workforce will change in the coming decades is critical to good labour force policy.

Allocate funding in the upcoming budget to create a proactive strategy for retraining workers in sectors impacted by climate change today. Easing the transition of skills between trades and in occupations impacted by the transition will be critical. A key part of any strategy must be encouraging labour mobility. Regulators must collaborate to break down interprovincial mobility barriers for workers to facilitate smooth work transitions.

Revise immigration strategies to ensure Canada is attracting, recruiting and integrating newcomers with the right skills for green collar jobs. Immigration targets should be reviewed and reshaped to reflect current and future demands for skills to support the Net Zero transition. Greater effort should be paid to mirroring credentials so workers can more rapidly become a productive part of the labour force.

Provincial labour regulators should work together to standardize job requirements in sectors that will need to draw labour from other parts of the country or world. Canada will need to draw on new pools of talent both within its borders (women, Indigenous people and youth) and beyond (immigrants).

Create new and accessible pathways for green skills training and careers through work-integrated learning and upskilling and re-skilling programs. Post-secondary institutions and employers should find new collaboration models to create quality green collar programs. Special focus should be paid to small and medium-sized enterprises, underrepresented Canadians and those whose livelihoods are most disrupted by climate change.

1. ECO Canada, “From Recession to Recovery”, March 2021.

2. https://cleanenergycanada.org/report/the-new-reality/

3. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2021063-eng.htm

Contributors

- Colin Guldimann, Economist

- Naomi Powell, Managing Editor, Economics and Thought Leadership

- Darren Chow, Senior Manager, Digital Media

- Trinh Theresa Do, Senior Manager, Thought Leadership Strategy

- Jennifer Marron, Producer, Disruptors

- Ben Richardson, Research Associate

Acknowledgments

In addition to those cited in this report, we thank the following individuals and organizations for their insights:

- Nelson Leite, Chief Operating Officer, FuelPositive Clean Energy Solutions

- Kim Olson, Executive Director, EnviroTREC

- Mark Kirby, President and CEO, Canadian Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Association

- Beth McMahon, Executive Director, Canadian Institute of Planners

- Gordon Beal, Vice President – Research Guidance and Support, CPA Canada

- Gord Forstner, President, Forstner Group Inc.

- Jim Szautner, Dean of Manufacturing and Automation, SAIT

- Alan McClelland, Dean, School of Transportation, Centennial College

- Mehran Ahmadi, Associate Director and Lecturer, School of Sustainable Energy Engineering, Simon Fraser University

- This report was produced within RBC’s Humans Wanted research program, but several adjustments were necessary to reflect the specific nature of green work.

- The data rely heavily on the O*NET occupational database, and work O*NET has done to map green tasks within jobs, in consultation with firms and occupational experts. The data were first collected in 2011, and have been continually updated.

- Note: changing tasks do not necessarily require a fundamental shift in underlying skills. More effort is needed to assess how skills may change in existing occupations.

- Task data was combined with O*NET classifications of occupations as new green occupations, green occupations requiring enhanced skills, and those seeing increased demand for their skills due to the greening of the economy.

- We used a mapping of O*NET-SOCs (detailed US occupation codes) to Canadian National Occupation Classifications (NOCs) provided by the Labour Market Information Council. In some cases, SOCs and NOCs map in complicated ways, so some judgement in classifying an NOC into the green occupation categories was needed.

- In addition to the underlying data, we consulted a range of industry, labour groups, and education experts to provide additional information about current challenges related to greening the labour force. We thank them for their insights.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates. This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward- looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social- impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.