- Though pandemic disruptions prompted widespread calls for reshoring, there’s little evidence of supply chains returning to Canadian soil.

- Factory construction in Canada fell to a decade low last year and manufacturing employment is close to flat amid labour shortages.

- Domestic production is only winning out over imports in areas where Canada was already an important player.

- But Canadian manufacturers are taking other actions to boost supply chain resiliency by diversifying suppliers and holding more inventory.

- The bottom line: While the government is targeting domestic production in certain sectors, there’s limited evidence of a broader reshoring push delivering a Canadian manufacturing renaissance.

The pandemic sparked calls to bring production home

COVID-19 shocked global supply chains, prompting manufacturers to pivot production to medical equipment, and governments to scour global markets for life-saving vaccines, PPE and other goods that couldn’t be made at home. At the same time these shortages were exposing the lack of domestic production capacity for critical goods, factory closures, input shortages and logistical bottlenecks were revealing the fragility of global production networks. Together, these forces kickstarted a wave of enthusiasm around “reshoring” or undoing decades of outsourcing in order to revitalize domestic manufacturing and insulate economies from future shocks.

As we wrote last year in our Trading Places report, governments are engaging in activist industrial policies to build new domestic and regional supply chains in an effort to limit reliance on rivals. But bringing existing offshore production home and unwinding complex supply chains is another matter. And more than two years into the pandemic, there’s little evidence it’s happening.

Canada’s industrial policies include government support for domestic vaccine production and for retooling existing auto facilities to make electric vehicles. But beyond this, there’s not much to suggest a broader manufacturing resurgence is underway.

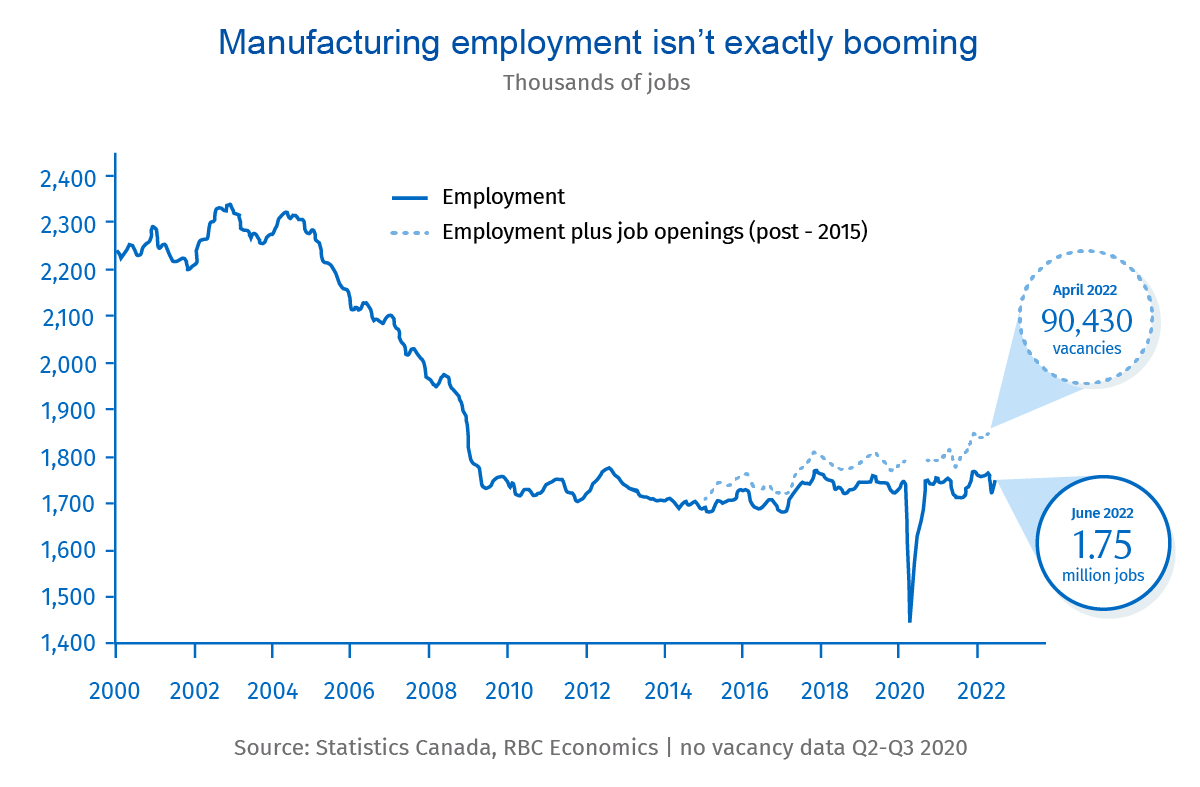

For one thing, employment in the sector isn’t exactly booming. In fact, it’s little changed from its pre-pandemic level, or the average seen over the past decade. Actual labour demand appears to have strengthened with a record 90,000 job openings in manufacturing. But that begs the question, how can Canadian businesses reshore production if they can’t fill vacancies? Labour shortages could be a key barrier to reshoring. Automation might be the answer, though Canada is a laggard when it comes to installing industrial robots. Manufacturers’ machinery and equipment investment intentions rose in 2022 but investment in factory construction fell to a decade low last year when adjusted for inflation.

But there are few signs of production returning to Canadian soil

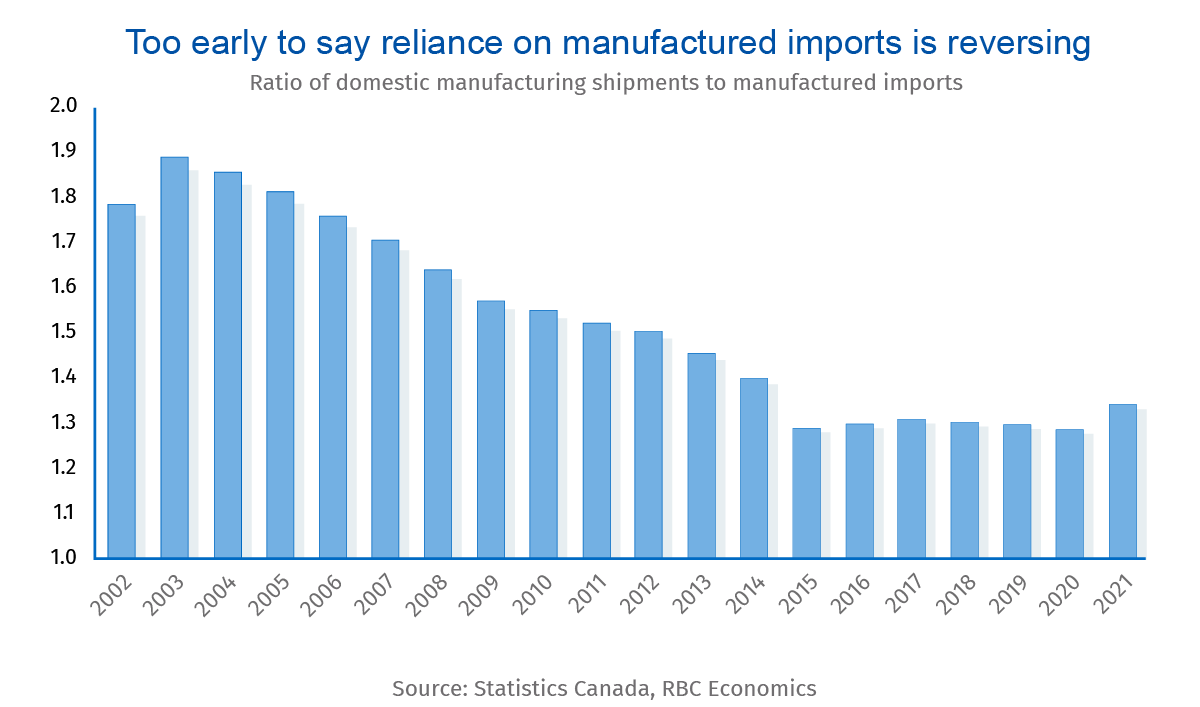

There was a relative increase in domestic manufacturing compared to manufactured imports in 2021 and again in early 2022—perhaps providing some evidence of domestic industry winning out over foreign production. But digging into the details, the only industries that saw a notable increase in domestic manufacturing were those in which Canada already had an edge, producing significantly more than it imported.

Production increased most in sectors like wood product manufacturing, petroleum and coal products, and food manufacturing—none of which rely significantly on imports to begin with. Industries dominated by foreign goods, like computer and electronic and electrical equipment manufacturing didn’t see any increase in production relative to imports.

If reshoring is about bringing back offshored production—not simply leveraging a country’s comparative advantage and increasing production that was always here—this has yet to occur in a significant way.

Canadian supply chains are longer and more global than ever

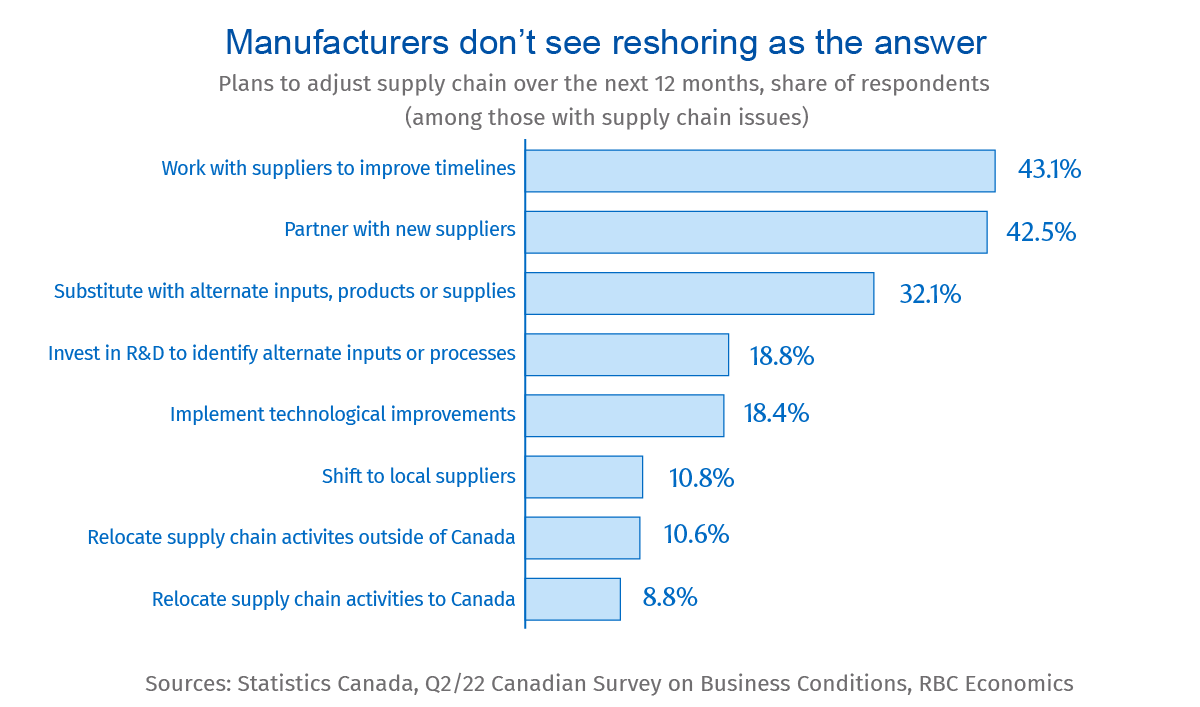

Perhaps this shouldn’t be surprising. After all, when manufacturers facing supply chain issues were asked how they planned to respond, relocating supply chain activities to Canada was last on their list. In fact, slightly more said they planned to relocate supply chain activities outside of Canada. In lieu of reshoring, firms plan to work with suppliers to improve delivery times, partner with new suppliers or substitute with alternatives. Indeed, Canada continued to diversify its imports in 2021, reducing its reliance on any single trading partner.

If firms aren’t relocating supply chain activities to Canada, are they at least “near-shoring” or bringing them closer to home? This doesn’t appear to be the case. In fact, Canada’s imports are coming from further afield than ever before (based on the geodesic distance between Canada and its trading partners). Over the course of the pandemic, several Asian countries, most significantly China, increased their share of Canada’s import market at the expense of countries like the US, Mexico and the EU.

Finally, it’s worth noting that reshoring could be a two-way street, with domestic jobs and investment potentially exposed to other countries’ efforts to bring production home. Canadian manufacturing relies on foreign capital—FDI in the sector is 1.7 times Canadian direct investment abroad. More than one in three manufacturing employees work for a foreign multinational, nearly three times the rate of the broader Canadian economy. And for every foreign worker employed by a Canadian manufacturer abroad, 1.2 Canadians are employed domestically by a foreign multinational.

Given this, a broader reshoring push might not be a good thing for Canadian manufacturing. On the contrary, the sector might be better served by other efforts to improve supply chain resilience, which already appear to be underway. While government policies might support domestic production in a few strategic areas, few businesses seem to see reshoring as the answer to supply chain issues.

Josh Nye is a senior economist at RBC. His focus is on macroeconomic outlook and monetary policy in Canada and the United States. His comments on economic data and policy developments provide valuable insights to clients and colleagues, and are often featured in the media.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates. This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward- looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social- impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.