- Home ownership is the primary method of accumulating wealth in Canada with nearly half of the household wealth amassed over the past three decades driven by residential real estate.

- At the same time, home ownership has never been less accessible. More than two-thirds (68%) of Canadian households can’t afford to purchase a home based on earned income alone.

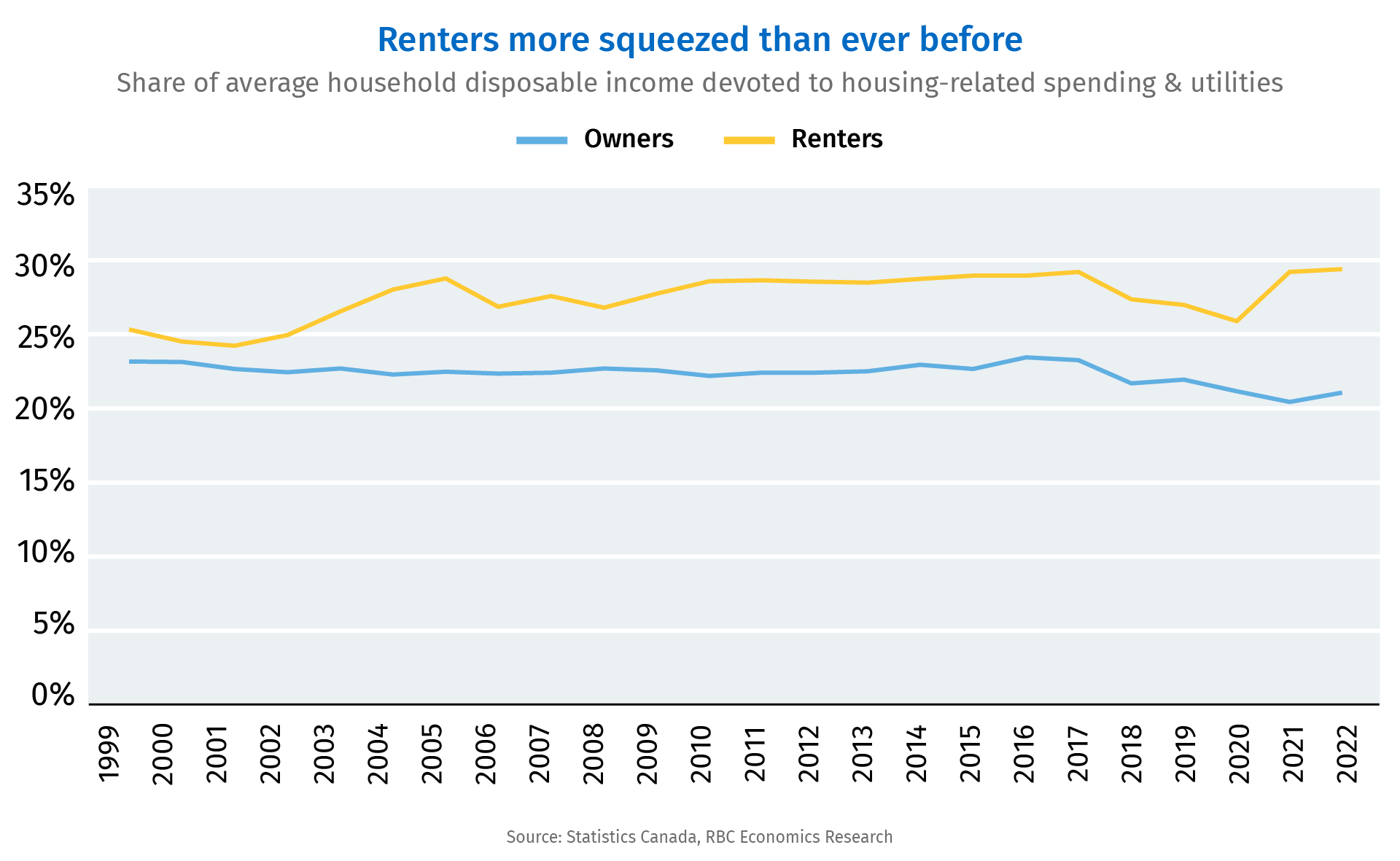

- Canadian renters are devoting a greater share of their take-home pay to housing costs, much more than homeowners. Many renters may not be able to enter the housing market with the limited scope to save for a down payment. As a group, renters spend more than they earn.

- Proof Point: Canadian renters are getting squeezed more than homeowners, making home ownership an even more distant dream. This threatens renters’ path to accumulating wealth—which could exacerbate inequality over the longer term.

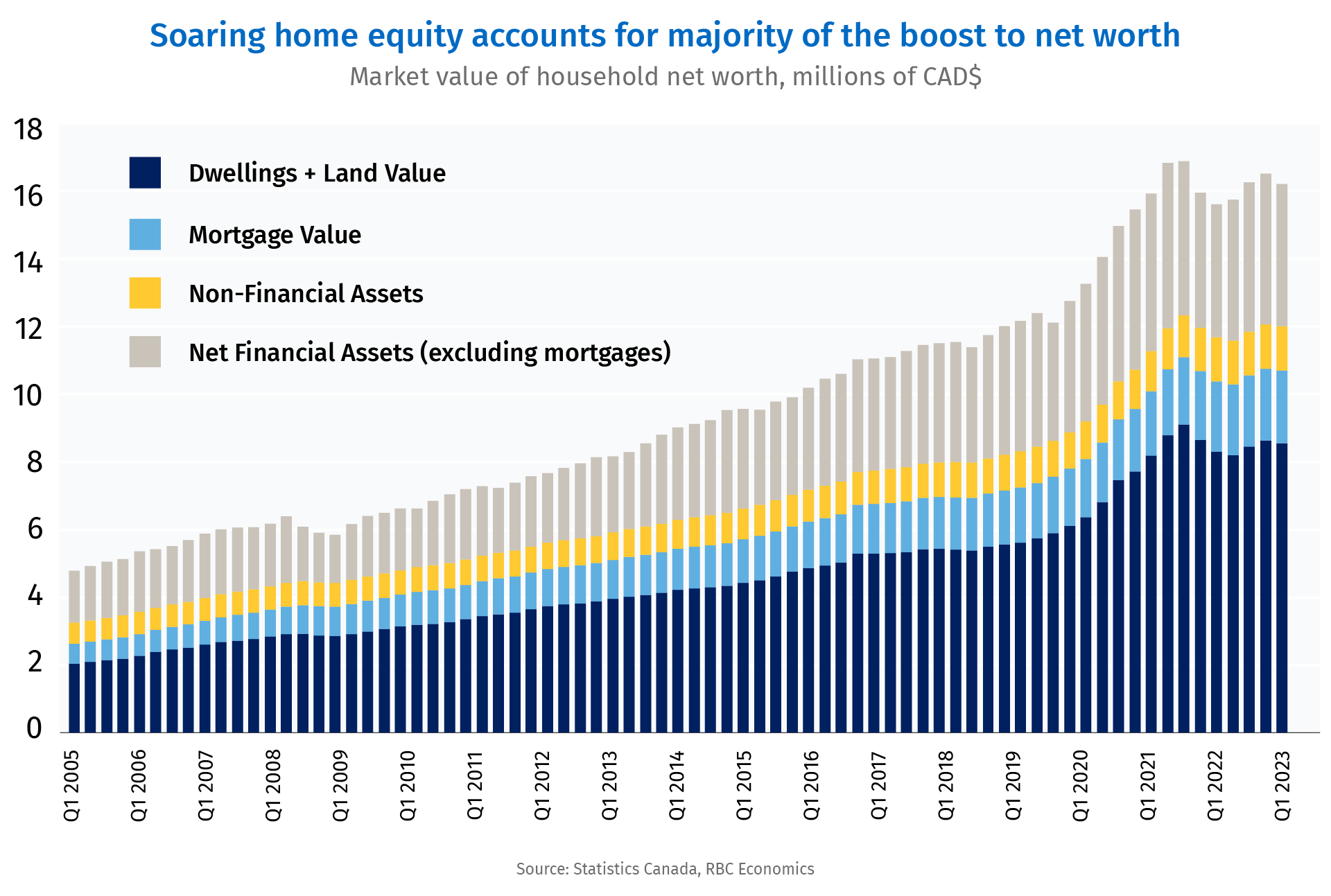

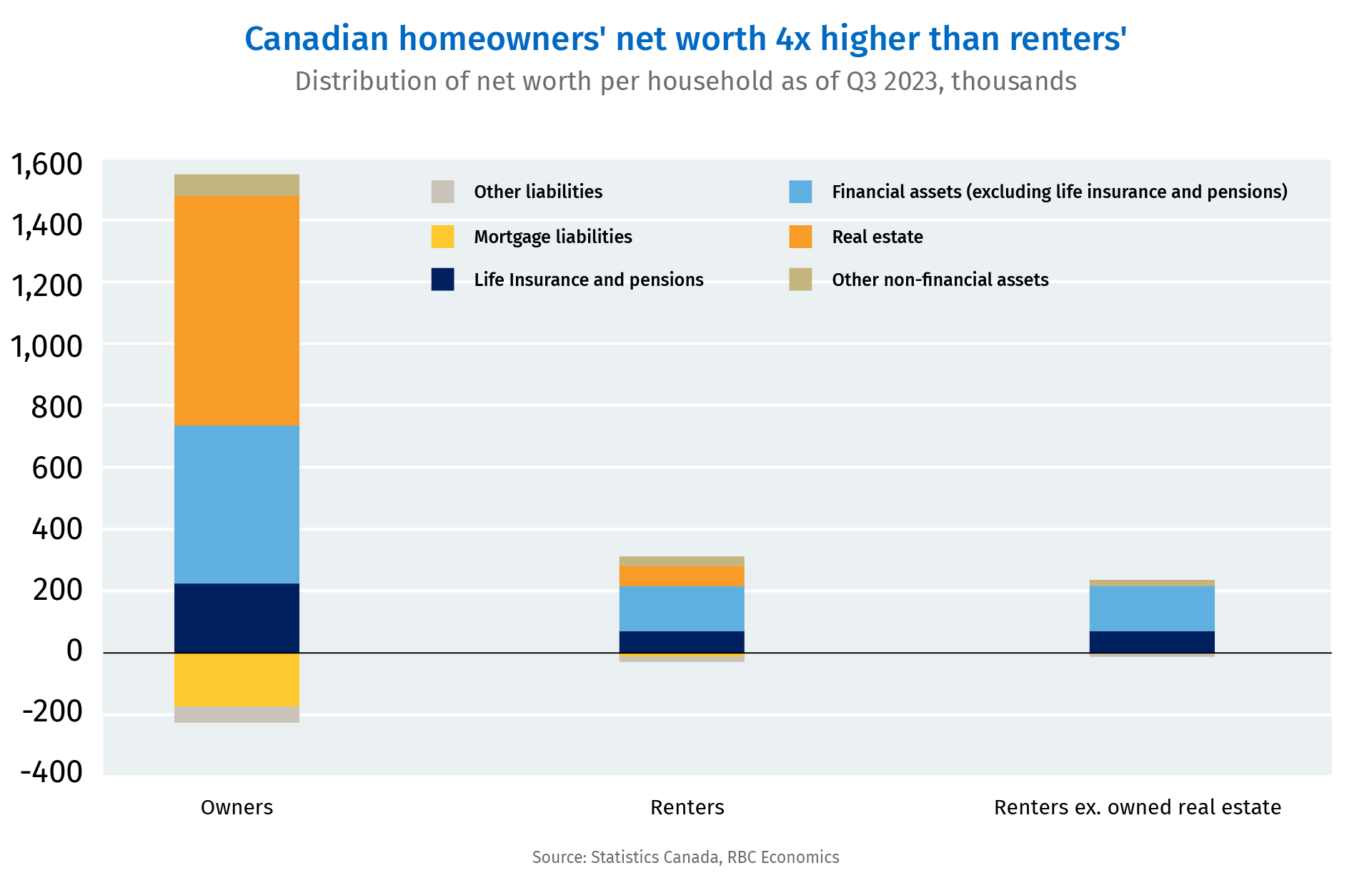

Canadian housing has long been the primary driver of wealth accumulation. Nearly half of Canadian wealth accumulation has been driven by home ownership for the past three decades. Homeowners saw their net worth grow from nine times household disposable income to 13 times since the fourth quarter of 2010. For renters, the appreciation has been a fraction of that magnitude. Net worth grew from three times to 3.5 times over the same period excluding residential real estate owned by renters1.

Pandemic gave brief reprieve for renters but pressures have returned

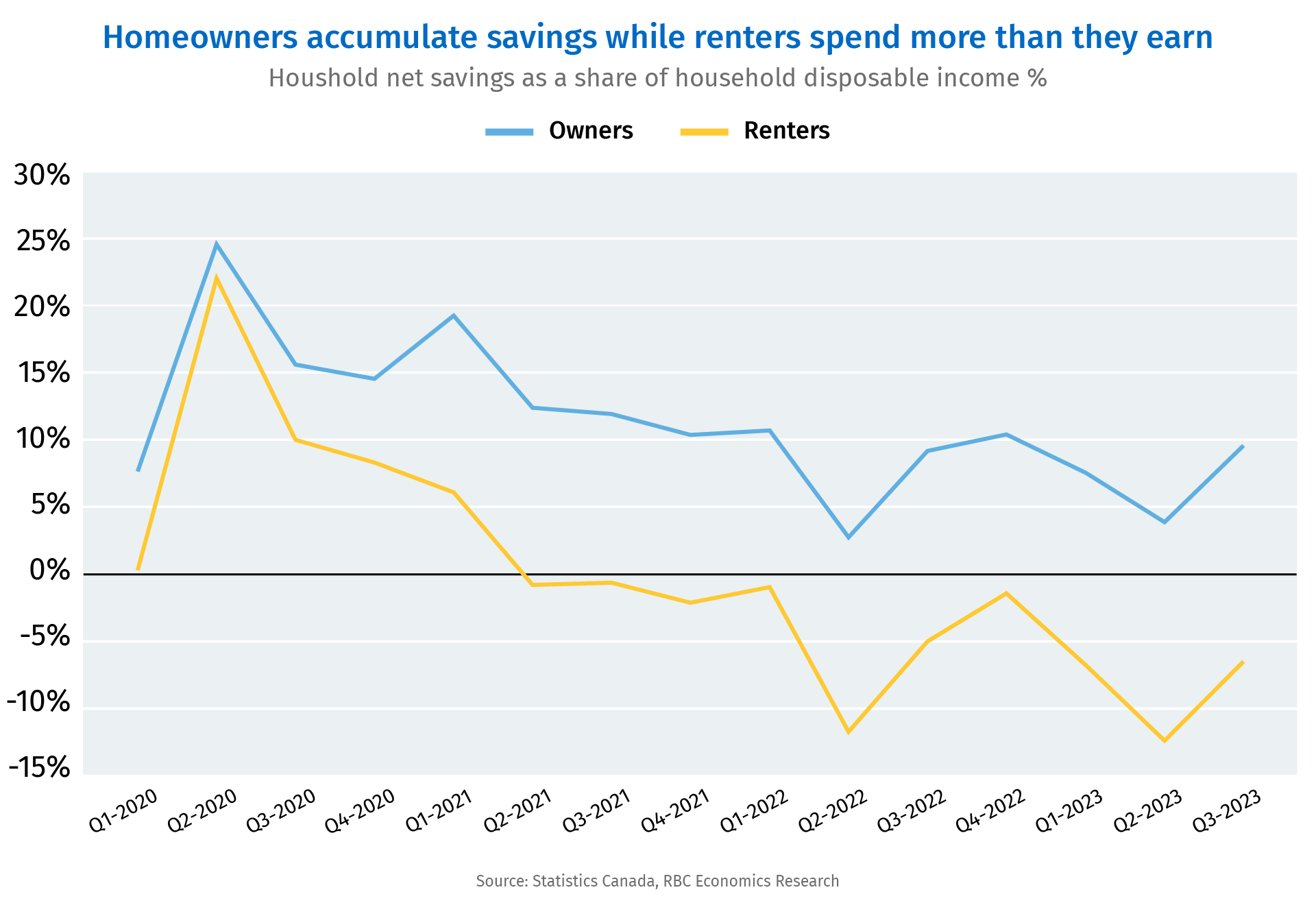

Historically, renters have largely been at the lower end of the income scale. As such, many who dreamed of owning a home struggled to save enough for a down payment. The combination of government grants to households during the pandemic and limited options to spend, however, sent household savings surging for renters and homeowners in early 2020. For Canadians who rented their primary residence, net savings as a share of household disposable income hit 22% in Q2 2020—a small difference from the 24% of disposable income saved by homeowners. Both homeowners and renters experienced exceptional wealth accumulation from pre-pandemic to Q2 2023 with net worth up 34% for homeowners and 23% for renters2 (with no real estate assets).

The third quarter of 2023 was the turning point when both homeowners and renters saw declines in net wealth. But renters have undoubtedly been hit the hardest . In addition to experiencing a pullback in pandemic-accumulated wealth (in large part due to a decline in the value of financial assets), Canadian renters as a group are once again dissaving—or spending more than they earn each quarter. Collectively, renters spent nearly 9% more than they earned in household disposable income in 2023, while homeowners saved 7% of their take-home pay.

Lower-earning renters are being squeezed to a greater extent

Both renters and homeowners have been impacted by higher housing costs in recent years, but renters are being squeezed to a greater extent because they have lower household incomes on average. And even though renters’ incomes have risen at the same pace as homeowners’ since the late 90s, the share of income that they allocate to housing has grown rapidly. In 1999, renters allocated an average of 25% of their take-home pay to housing costs including utilities. This was slightly more than homeowners, who devoted 23% of their take-home pay during the period. The gap has widened significantly. In 2022, renters devoted 29% of their after-tax earnings to housing compared to 21% for homeowners (who accumulate savings in the form of home equity through these allocations). Lower earnings and higher allocations to housing make it exceptionally difficult for renters to save for a downpayment- a crucial step in the path to wealth accumulation.

Home ownership has become extremely difficult

Canada’s home ownership rate is still relatively high. Two-thirds of the population own residential real estate as of 2022, but this is changing as affordability worsens. It has never been more difficult to get into the housing market.

Renters dissave to a greater extent because they are grappling with higher living and debt-servicing costs, making saving for a down payment harder than ever. Only about one-third of Canadian income earning households earn enough to purchase a single-detached home on their income alone. This is a stark difference from 2005 when half of Canadians earned enough to purchase a home on just their income. More middle and upper-income earners could join the renting population if ownership affordability does not improve and more Canadians get priced out of the housing market.

Canada could become more unequal in the future

The purchase of a first home used to be a rite of passage that came with building a family, but now home ownership is more likely to be associated with an inheritance or the transfer of wealth from previous generations. Since 2010, homeowners’ real estate assets (excluding the value of mortgages) have grown four times faster than life insurance and pension savings. Home equity has largely been viewed as a nest egg to fall back on. But with access to home ownership more constrained, some Canadians may not reach their savings goals in the absence of alternative vehicles for wealth accumulation. The risk of greater inequality between renters and homeowners is one of the many reasons why Canada must address its housing crisis.

-

1. Some Canadians who rent their primary residence do own real estate.

2. Pandemic wealth accumulation for renters was largely driven by an appreciation in the value of financial assets.

Carrie Freestone is a member of the macroeconomic analysis group and is responsible for examining key economic trends including consumer spending, labour markets, GDP, and inflation.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates. This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward- looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social- impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.