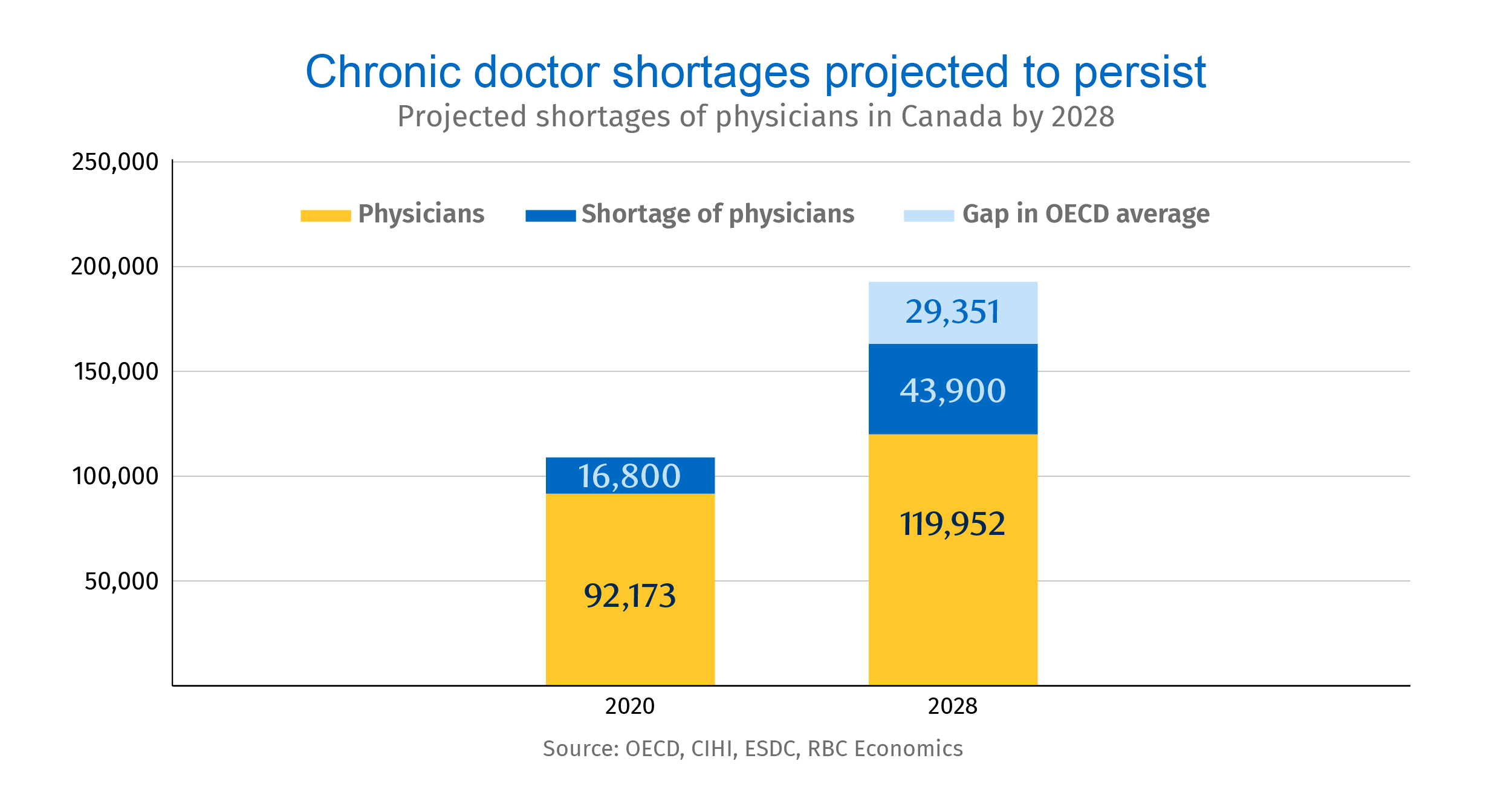

- Canada will be short about 44,000 physicians by 2028, with family doctors accounting for 72% of the deficit.

- In addition to closing that gap, Canada will need to train or hire 30,000 more physicians by 2028 to match the average number of doctors per capita among OECD peers.

- Limited residency spots, a lack of professionals to evaluate prospective physicians, and funding shortfalls have created a chain of bottlenecks.

- And the shortages are adding pressure to an already strained healthcare system, as patients unable to find family doctors turn to emergency rooms instead.

- The bottom line: Hiring and training more doctors specializing in high-demand disciplines will help alleviate chronic shortages. Adding residency spots for fresh domestic and international medical graduates can help address some long-term challenges. And technology and policy that support the current workforce can improve efficiencies.

The doctor is out: a severe shortage of physicians is fast approaching

Finding a family doctor in Canada is getting harder. Roughly six million Canadian adults don’t have access to a family doctor—up from 4.6 million in 2019. The situation is particularly alarming in rural communities where only 8% of physicians are serving nearly one-fifth of Canada’s population. The pain of this shortfall is already being felt in the broader healthcare system. Family doctors are often the first stop for patients seeking medical attention. And without quick access to them, patients are turning to emergency departments already overwhelmed by the pandemic.

The crisis is set to deepen. Canada is estimated to be short nearly 44,000 physicians, including over 30,000 family doctors and general practitioners, before the end of the decade. Though 2,400 family physician positions were advertised on government websites by the end of 2021, just 1,496 family doctors exited residency training that year.

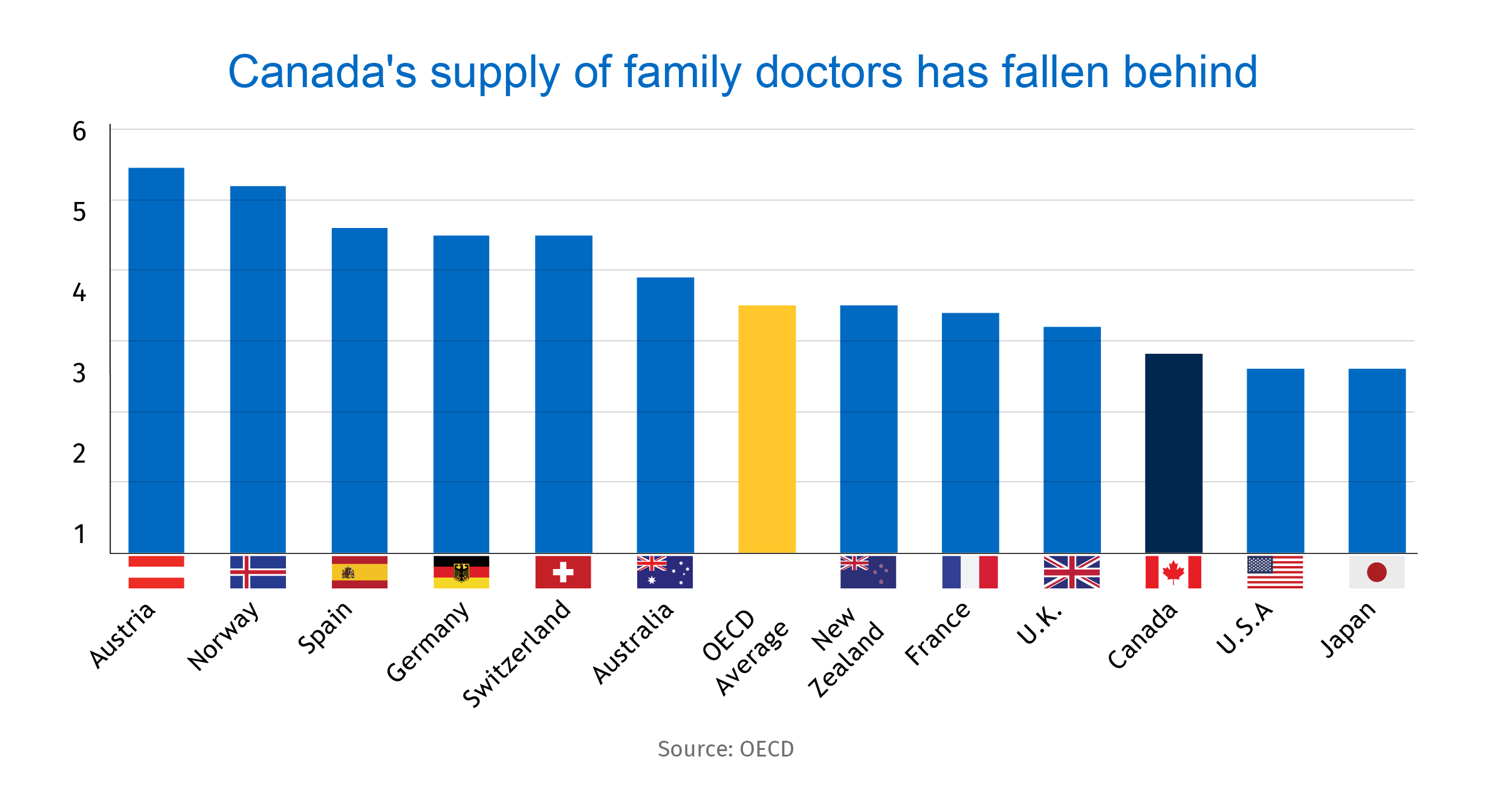

Canada’s supply of doctors has fallen behind other major economies

The number of doctors per capita in Canada is well behind that of peer countries like France and Germany, according to OECD data. What’s more, due to data comparability issues, these figures paint a rosier picture for Canada by including non-practicing doctors (educators, researchers, managers, etc.) in overall physician statistics. With Canada’s population set to rise 7.7% by 2028, addressing this primary healthcare crunch is critical. But easing bottlenecks across the system is more complex than simply recruiting more domestic and international individuals to study medicine.

The first choke point is a quota system that all 17 Canadian medical schools are subject to, and that limits student admissions to just under 3,000 spots for prospective doctors each year. The second is the disproportionate number of graduates from international medical schools (both Canadian and foreign-born) who don’t end up with residency positions. Over 90% of the roughly 2,100 applicants who went unmatched in the past three years were international medical graduates (IMGs). The third is the expansion of quotas for medical students without a commensurate increase in residency opportunities—a vital requirement to practice medicine.

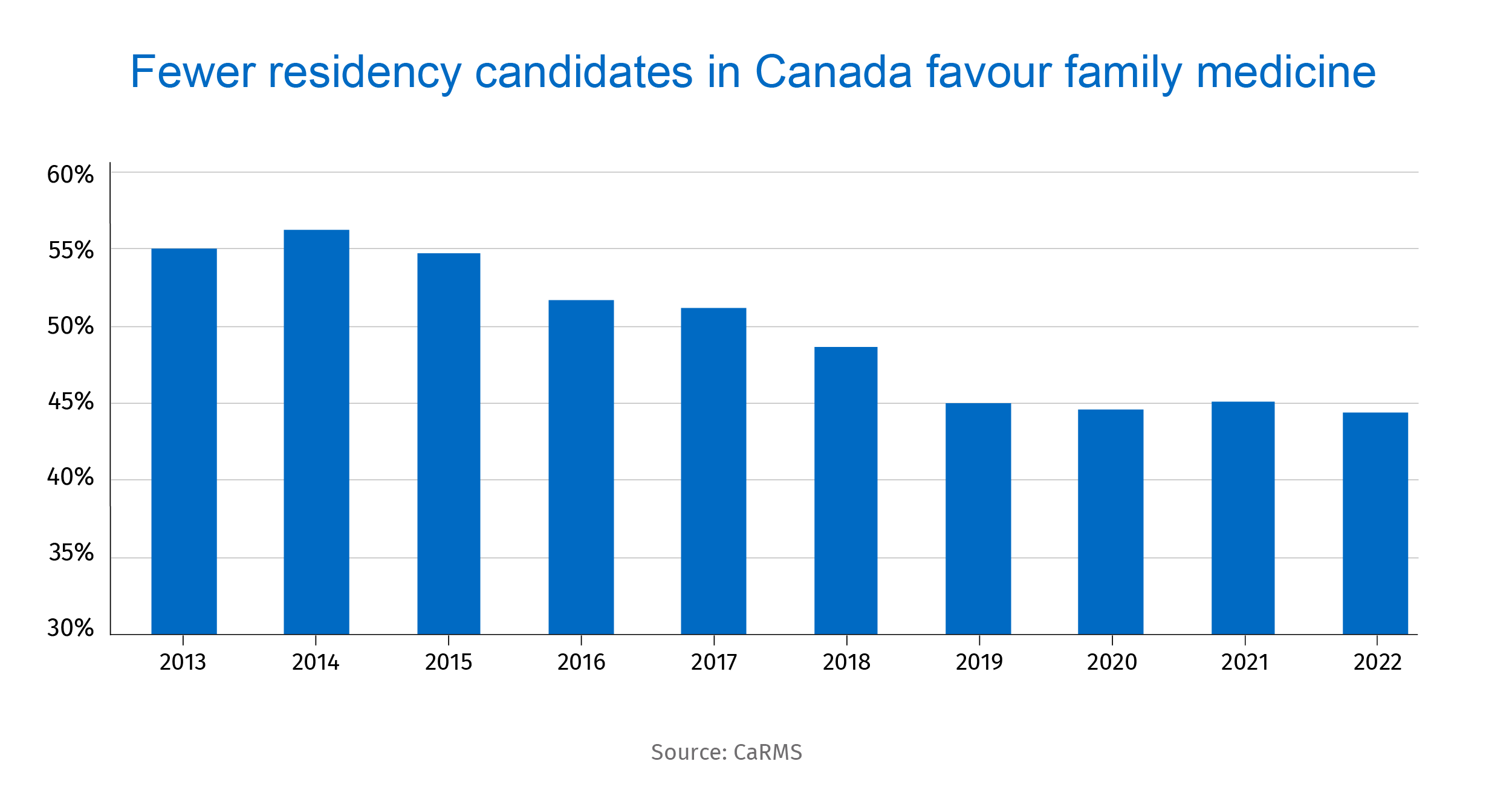

The final bottleneck is the declining share of medical students choosing to study family medicine—the discipline most in demand in Canada. An incentive drive to encourage more people to pursue this career, and for medical practitioners to take trainees, is urgently needed.

Streamlined credentialing, more funding needed to curb doctor shortage

Investment will be needed to expand the capacity of hospital and university networks, to add educators and assessors, and to increase residency spaces in the Canadian medical system. More residency spaces are also needed to align with the increase in medical school student quotas. And streamlining credential recognition for internationally-trained physicians (ITPs) and international medical graduates (IMGs) will be crucial. Programs like Practice-Ready Assessment (PRA) can assess ITPs and IMGs in a clinical environment over a period of twelve weeks by evaluating candidates more practically and thoroughly while expediting their workforce integration. Currently, however, only seven of ten provinces employ PRA. Ontario, home to 39% of Canada’s population, scrapped the PRA program in 2018. This has exacerbated the province’s doctor shortage.

Many provinces are taking important steps to alleviate shortages. Ontario is making it easier for out-of-province physicians to temporarily practice in the province, while British Columbia is raising family doctors’ earnings. But more should be done to attract internationally-trained physicians who can begin providing care to Canadians quickly.

As we work to attract more trainees to family medicine, we can unlock other efficiencies, including by encouraging family physicians to work collaboratively with other healthcare professionals to ensure timely patient care. Technology can help streamline the prescription process, and telehealth consultations can reduce administrative burdens.

Ben Richardson Ben is responsible for researching pieces for RBC Economics and Thought Leadership. Prior to joining RBC, he obtained a Master’s degree from the University of Toronto and worked in Washington, D.C., at the Woodrow Wilson Center, researching topics concerning Canada-US relations.

Yadullah Hussain is Managing Editor, Climate & Energy, at RBC Thought Leadership. Before joining RBC, Hussain was a business journalist covering the economy, energy and financial markets in a career spanning two decades.

Naomi Powell is responsible for editing and writing pieces for RBC Economics and Thought Leadership. Prior to joining RBC, she worked as a business journalist in Canada and Europe, most recently reporting on international trade and economics for the Financial Post.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates. This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward- looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social- impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.