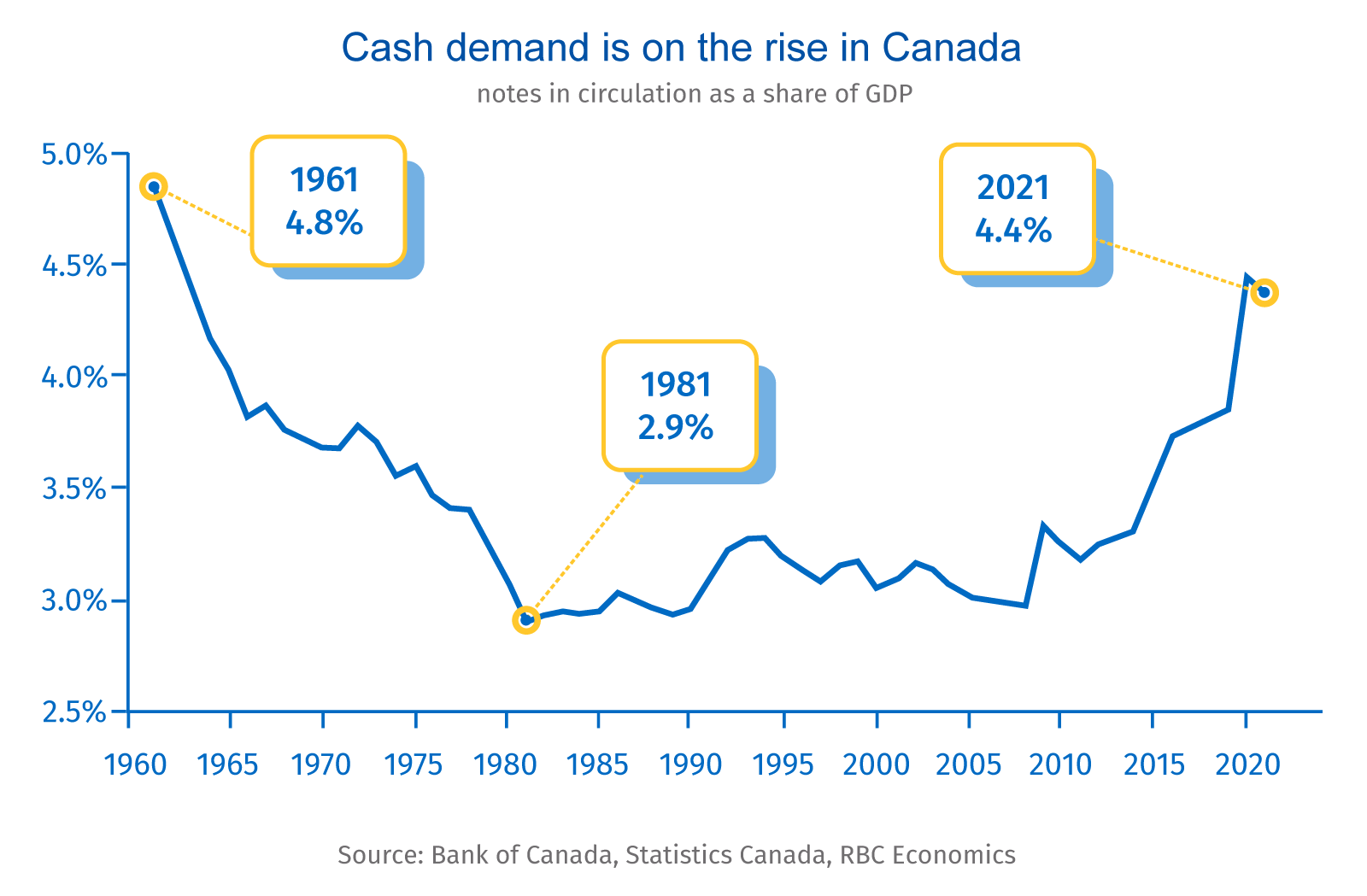

- Demand for cash is at its highest level in 60 years, despite a broad shift to e-commerce and virtual payments during the pandemic.

- Throughout the crisis, the use of cash in daily transactions continued a steady, long-run decline.

- But its use as a savings vehicle soared amid pandemic and geopolitical uncertainties, cybersecurity worries and low interest rates.

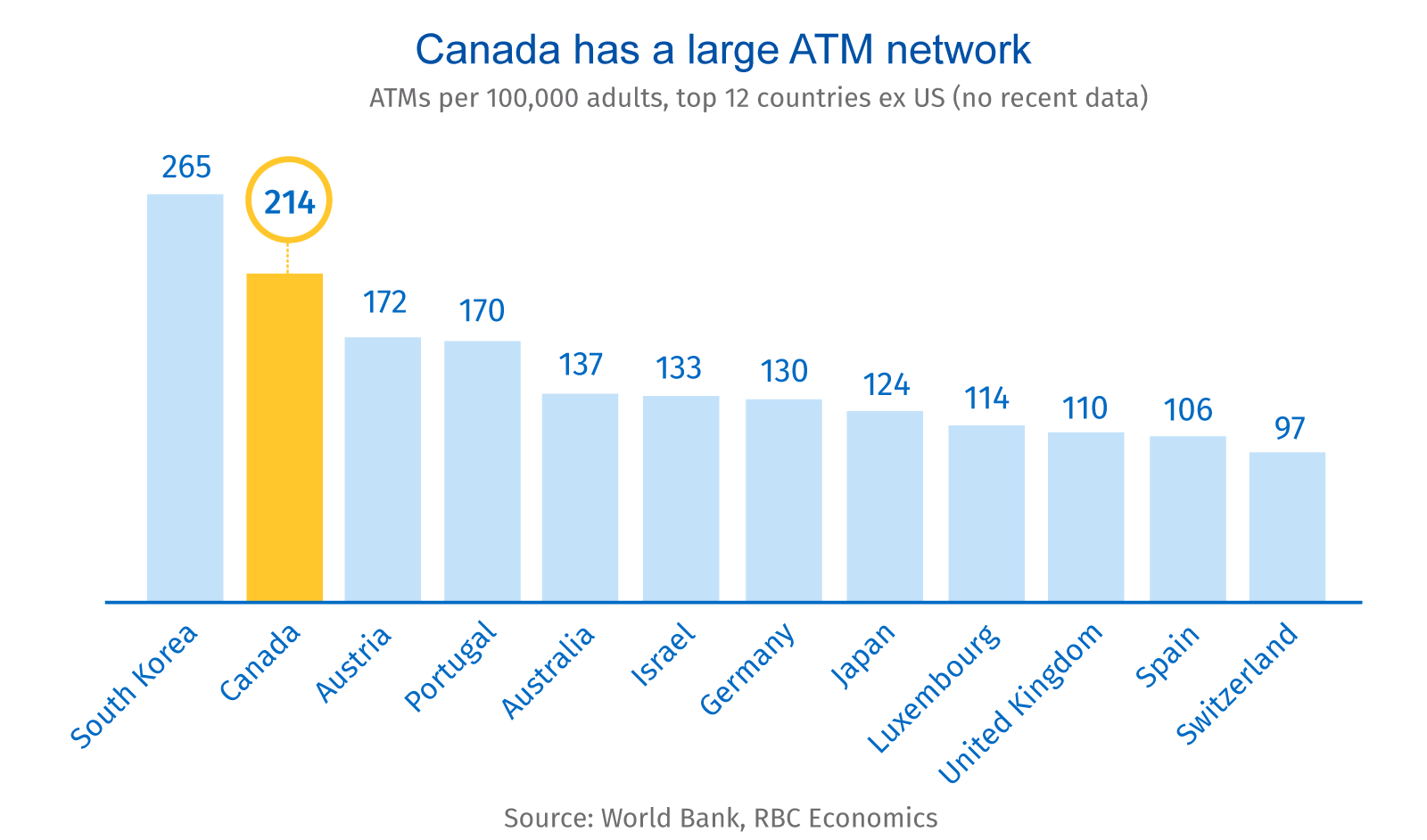

- Canada can reduce the cost of hard currency, including by streamlining the country’s large ATM network.

- The bottom line: As central banks design their own digital currencies, an examination of the factors behind cash’s appeal could be critical.

Canadians’ appetite for cash is growing

The pandemic didn’t kill cash. In fact, Canadians’ attachment to hard currency only grew stronger. Cash withdrawals rose sharply early in the crisis, as notes in circulation increased by twice as much as would have been expected in 2020, and remained elevated through 2021.

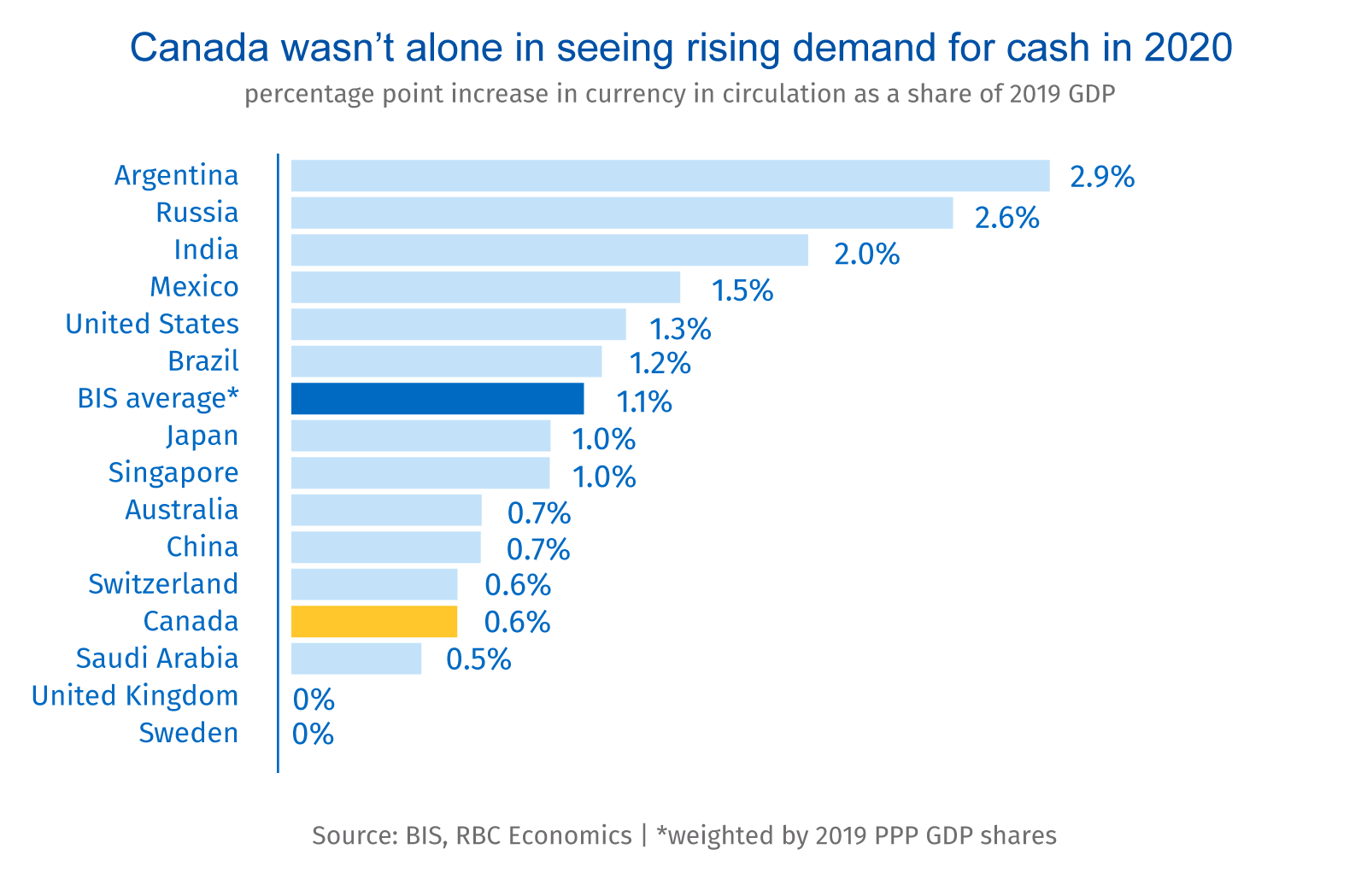

This trend isn’t unique to Canada. The U.S. and euro area saw an even greater increase in cash as a share of pre-pandemic GDP. Only more cashless societies like the U.K. and Sweden failed to see a pandemic cash bump.

Cash is no longer king in daily transactions

For the most part, those coins and bills weren’t spent at the grocery store or the gas pump. Indeed, though the pandemic didn’t reverse the long-running decline in cash transactions, it didn’t accelerate it either. Payment diaries show a nearly straight-line drop in the volume of cash transactions, from 54% in 2009 to 22% in 2020. Credit cards picked up much of that decline, particularly for e-commerce transactions and tap-and-go payments.

The pandemic gave cash a second wind—as a store of value

If Canadians aren’t using more cash for transactions, what explains its ongoing allure? Crises (or fears of crises) are often tied to a dash for cash. Demand for both small and large denomination notes increased globally at the turn of the century amid fears that the Y2K bug would cripple ATM networks and cashless payment systems. And large denomination notes saw greater demand during the global financial crisis when customers worried about banks’ solvency. Lower central bank policy rates are also associated with higher demand for large denomination notes—which tend to play a store of value (savings) role.

On that basis, Canadians appear to be driven by a desire to stash, not spend cash. Notes worth $50 or more accounted for all of the increase in currency demand (as a share of GDP) since 2014. The $100 bill now accounts for 60% of currency in circulation, up from 50% in 2010. Recent rising interest rates and multi decade-high inflation will likely take some but not all of the shine off cash as a savings vehicle.

Canada is a long way from cashless

The rise of e-commerce and digital methods of payment should also see cash lose more of its lustre, but Canadians aren’t giving up on cash just yet. As of August 2021, the Bank of Canada found 62% of survey respondents made a cash payment in the previous week, while a similar share made a debit card payment and 76% used credit cards. Fully 81% had no plans to go cashless. And among 13% of respondents who said they were already cashless, half still had some cash on hand.

Our penchant for cash is costing us

Cash has its costs, from maintaining ATMs and securely handling, storing and transporting hard currency, to tax gaps associated with underground economic activity. Moving to a cashless model would add about 1 percentage point to the annual GDP of mature economies, a BCG study found. That might be an overestimate for Canada, given its already relatively low cash-to-GDP ratio, high share of cashless payments and small “shadow economy.” At less than 10% of GDP, Canada’s shadow economy was the 10th smallest in the OECD in 2015, according to the IMF.

Canada has the second most ATMs per capita in the OECD since its low population density requires a larger network. The number of ATMs in the country has declined gradually since 2017 but deposits and withdrawals have fallen even faster. There might be scope to streamline the ATM network as the way we use cash continues to evolve—store of value demand might necessitate fewer withdrawals. But that will have to be balanced against maintaining ready access to cash for those who use it more frequently.

Going digital won’t be easy

As public money, cash is a direct claim on the central bank, with all the safety and security that brings. It’s proven to be a reliable store of value (aside from inflation) and is almost universally accepted as a payment.

The question for central bankers is how public money can continue to play that role in an increasingly digital world. That’s where central bank digital currency (CBDC) comes in—the design of which could determine its uptake. Central banks will have to balance some of the features consumers look for in both cash and crypto, like anonymity, with concerns about tax avoidance and money laundering.

There are aspects of cash, like the security offered by central bank backing, that translate well into CBDC. But growing concerns about cybersecurity that affect all forms of digital money could continue to give cash a leg up. Meantime the ongoing preference for cash as a savings vehicle may demand the future coexistence of cash and CBDC.

The story changes when it comes to payments, where cash is in decline. As hard currency becomes less relevant as a payment method, the Bank of Canada risks losing its role as a payment provider—a role that could prove valuable should private players come to dominate the market for digital payments.

Josh Nye Josh Nye is a senior economist at RBC. His focus is on macroeconomic outlook and monetary policy in Canada and the United States. His comments on economic data and policy developments provide valuable insights to clients and colleagues, and are often featured in the media.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates. This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward- looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social- impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.