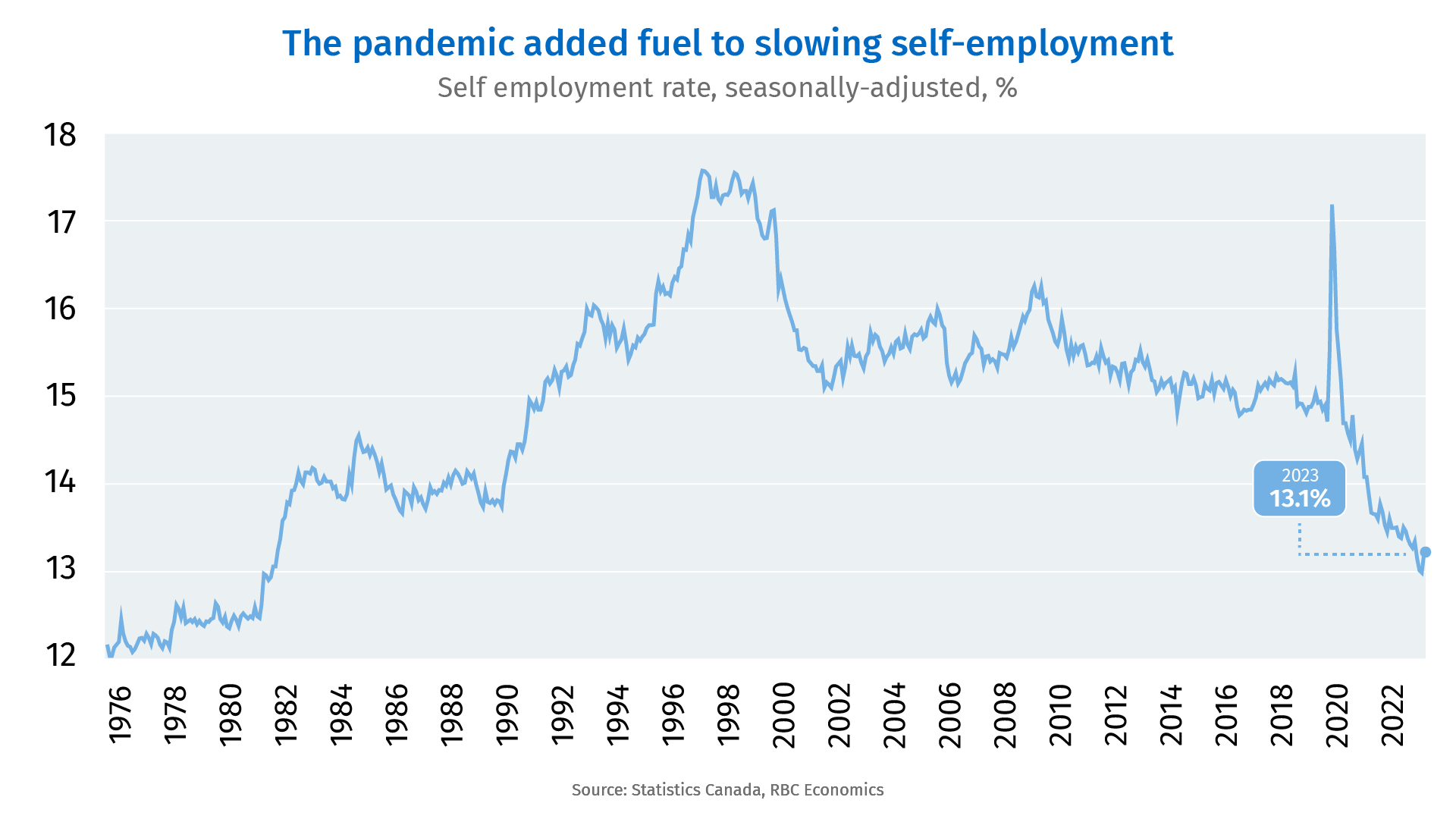

- The uncertainty of the pandemic, strong labour markets, and soaring inflation have sped up a decades-long decline in the self-employment rate.

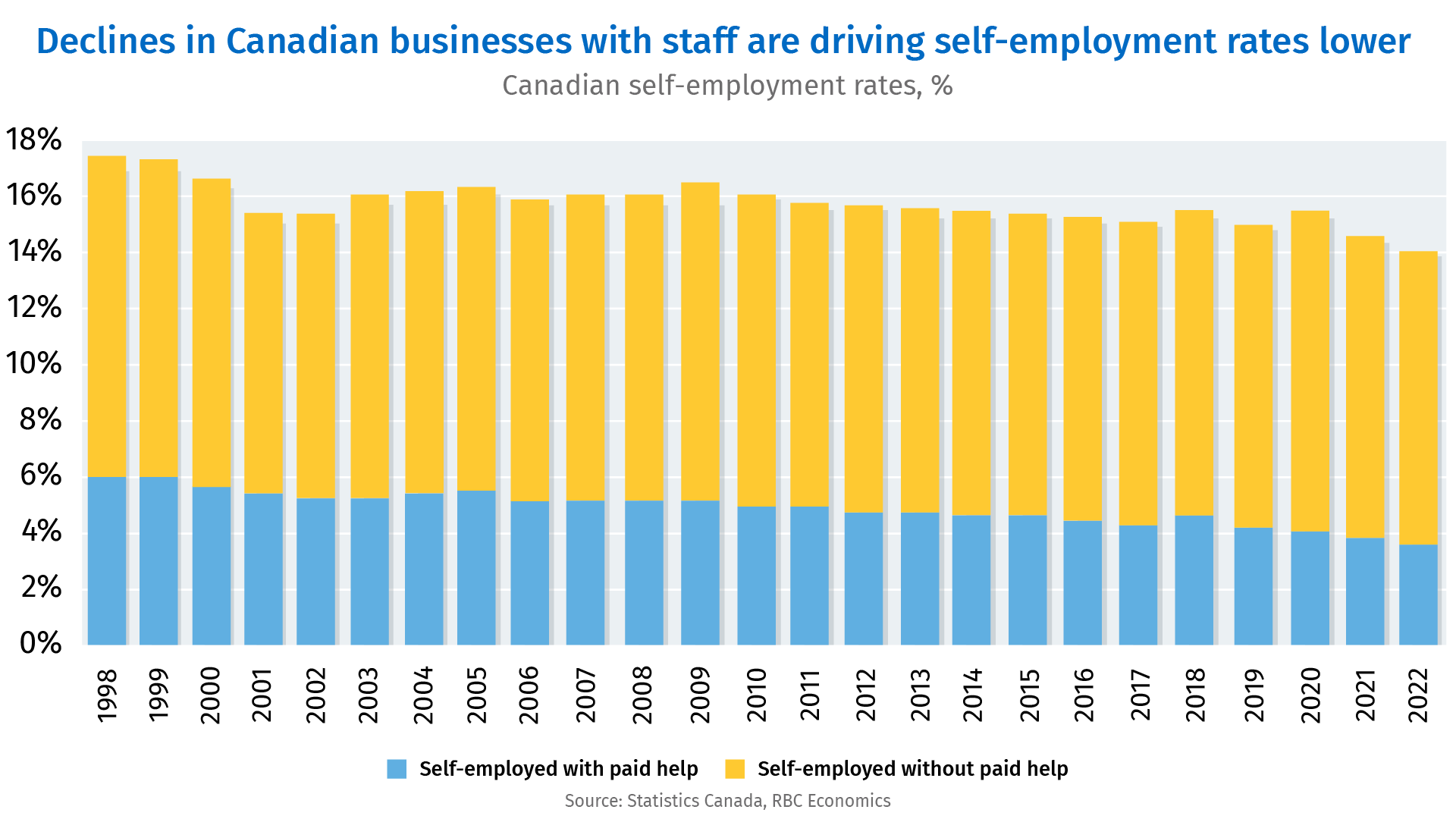

- Most of the pullback in self-employment comes from businesses with paid help. This could be a problematic trend for small business creation in Canada.

- Self-employment (with paid help) has become less attractive to Canada’s younger workers, a fact unlikely to change anytime soon.

- Bottom line: Entrepreneurship is becoming less enticing for Canadians. With Canada’s aging population, as more small business owners exit, there will be fewer nascent businesses to take their place.

Slowing self-employment rates are not just a post-pandemic trend

The pandemic accelerated a decades-long decline in the self-employment rate. But whereas pre-pandemic declines were driven by industry factors – and concentrated in the goods sector – since the pandemic the declining share of self-employed workers has been broad based.

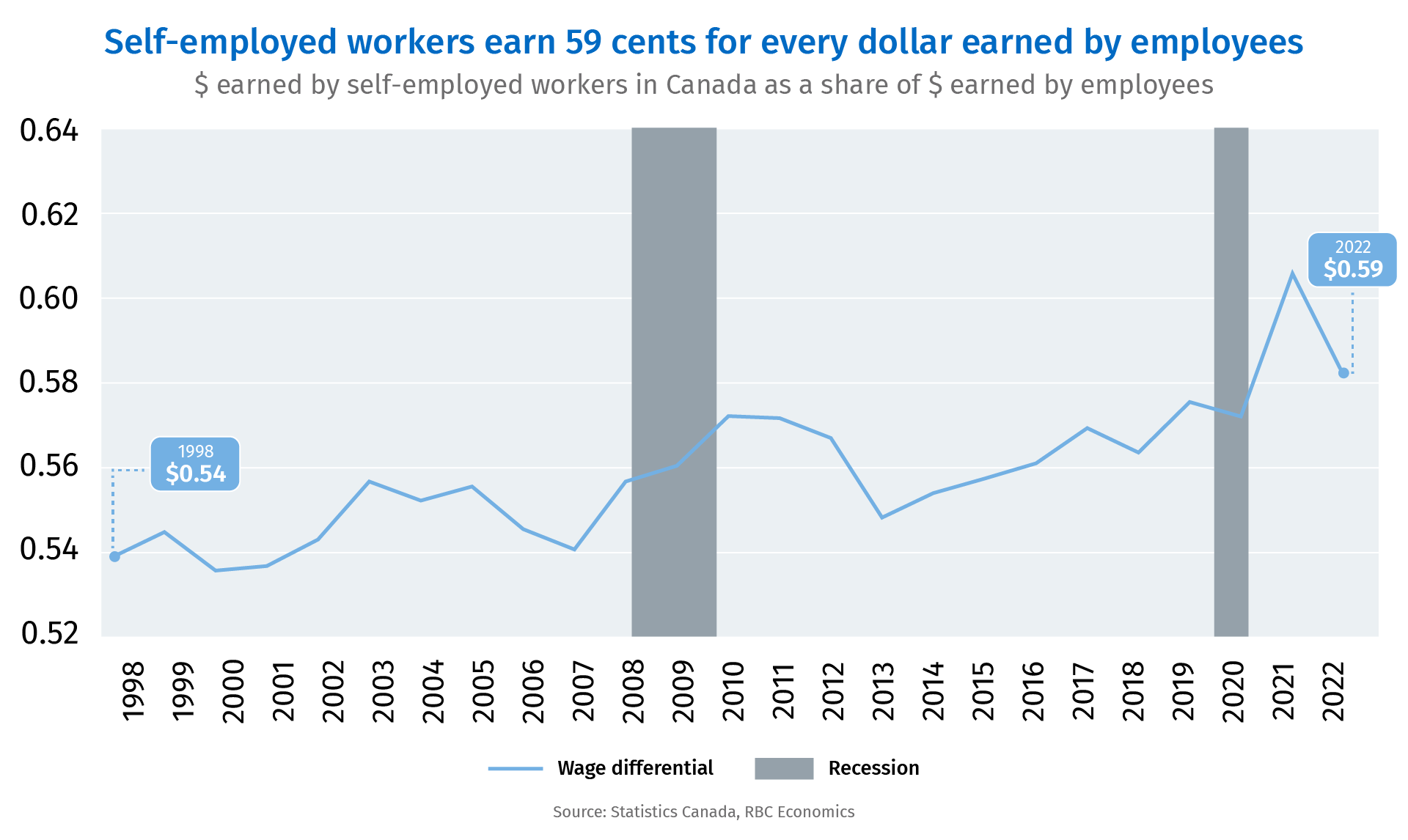

Strong labour markets and higher hourly wages for employees probably have something to do with it. For example, an employee working in professional, scientific, and technical services earns 20% more per hour (on average) than a self-employed worker in the same sector. Employers are also offering more flexible working arrangements previously only available to the self-employed.

Fewer Canadians choosing to head businesses could be problematic for entrepreneurship

Self-employment is a way for employees to break out on their own with a high potential business model. It can also be a second-best option for those unable to find suitable employer-paid work. Higher potential self-employment ventures are those that employ at least one (other) worker, and as such are considered businesses. 13% of Canadian workers are self-employed, but only 4% have employees as of 2022.

Unfortunately, Canada’s declining self-employment rate has been concentrated among those that could contribute most to entrepreneurship. Half of the 6% pandemic contraction in the number of self-employed can be explained by businesses with paid help. Pre-pandemic, while the self-employment rate was falling there was still modest growth in the absolute number of the self-employed, but those with paid help declined modestly. The result: the share of those with paid help among the self-employed has declined from 34% in 1998 to 27% at current.

Are we ageing out of an era of self-employment?

Canada’s population is greying, and as more Baby Boomers retire, Canada is slated to see a higher number of small business exits. Since only 9% of business owners have a written succession plan in place, this begs the question: will there be enough nascent businesses to fill their place?

Likely not. Although Canada’s expanding immigrant population has a somewhat higher propensity for self-employment, it is unlikely to compensate for self-employment being less attractive to younger workers. The decline in self-employment rates for business owners with paid staff is occurring across all age cohorts. Self-employment rates for younger Canadians (aged 35 to 44) has always been lower, but the share of younger Canadians seeking to “be their own boss” has fallen from 3.3% in 1998 to 2% at present.

Don’t expect a turnaround anytime soon. We expect softening demand for employees in the year ahead as interest rates continue to cut into economic growth could mean a shift to more workers in some form of self-employment as a main job. But the cost of living and housing affordability also continue to erode. And structural labour shortages are expected to underpin wage and benefits growth for paid employees in the decade ahead, making paid employment a more attractive relative option. And in the near-term, the higher interest rate environment will constrain consumer activity, creating a challenging environment for small businesses. These businesses face higher rents, higher capital costs, and must pay higher wages while consumer activity wanes.

Cynthia Leach is the Assistant Chief Economist, Thought Leadership at RBC. She leads the team’s forward-looking economic and policy analysis, covering topics such as human capital, innovation, and trade. She joined the team in 2020.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates. This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward- looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social- impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.