- A lower Canadian dollar, especially against the greenback, has sparked fears that import prices will rise—lighting up inflation just as it’s finally settling down.

- But with domestic services dominating more of what we buy and Canada importing more from countries outside the U.S., these currency fluctuations matter less to prices than they once did.

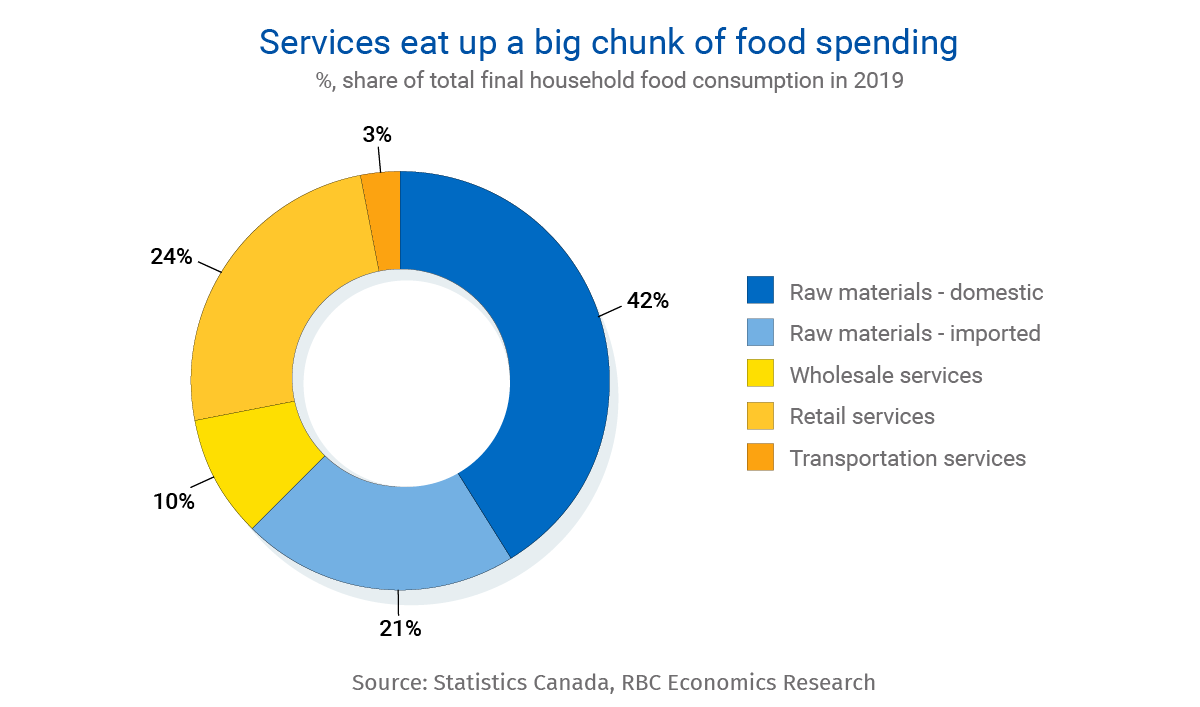

- Even for exchange-rate sensitive food products, one third of the $100 billion+ annually spent on food in Canada can be traced back to domestic services like shipping and retail.

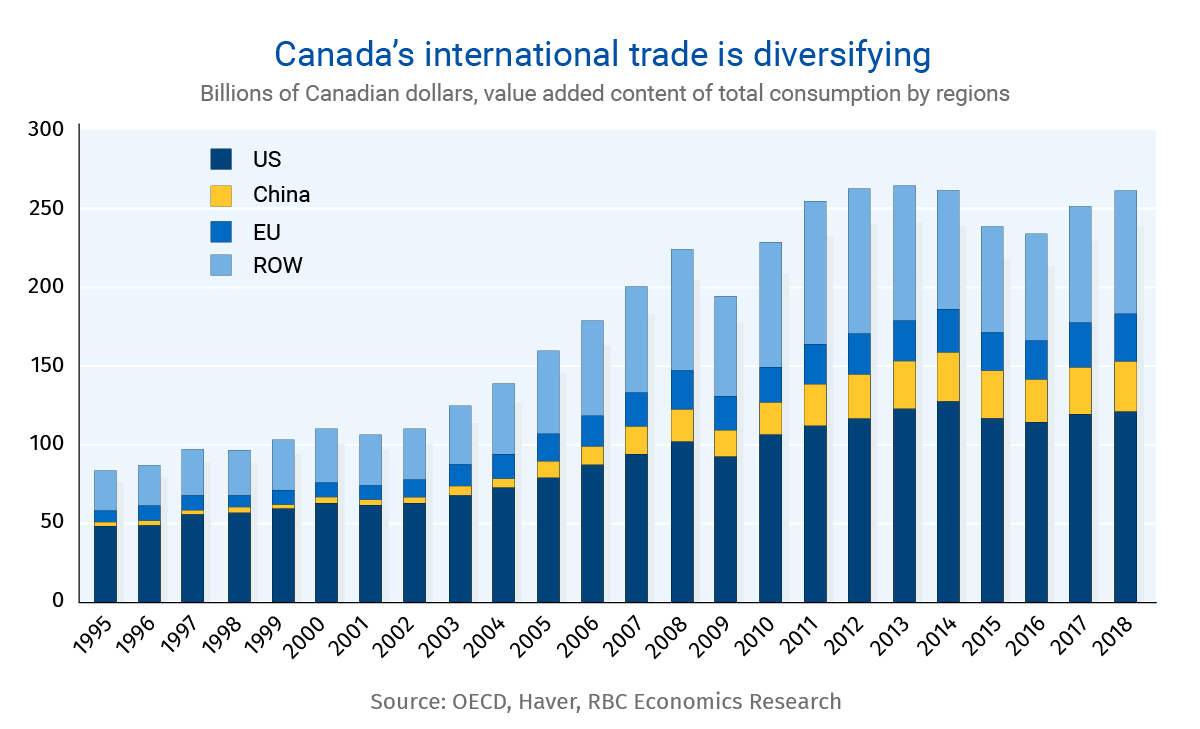

- And as the U.S. share of imports has fallen, Chinese imports have steadily risen (and the Canadian dollar is stronger against the yuan.)

- Bottom line: A weak CAD won’t derail inflation trends that are now heading in the right direction. In an increasingly services-dominant economy, demand, not currency, will decide where prices go.

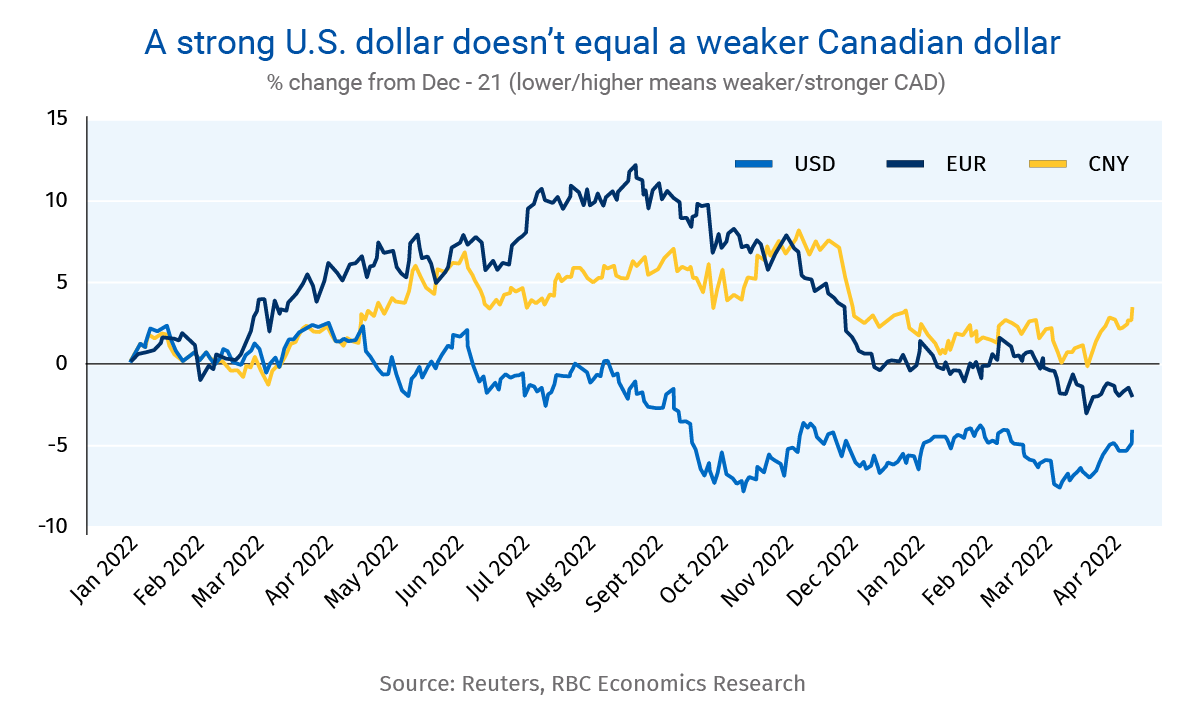

The Canadian dollar’s the softest it’s been in almost three years

Throughout much of 2022, rising uncertainty about inflation, economic growth and the war in Ukraine sent the greenback soaring. Meantime, the gap between key policy rates in Canada and the U.S. widened as the Fed continued its hiking cycle while the Bank of Canada announced a conditional pause. A weaker Canadian dollar means higher import prices. That’s fine in normal times, but with inflation flying high already, the concern is that a weaker CAD could worsen the burden of high prices. This could in turn push the BoC to follow the U.S. Fed by resuming rate hikes.

These concerns—while not entirely unwarranted—are often overblown.

Services matter more than ever

For one thing, Canada is increasingly a services economy.

The OECD estimates that 80% of the value of total goods and services consumed (spending from households, government, and non-profit institutions) in Canada is produced domestically. Over half of those expenditures are on services (things like rent, education, and childcare) that aren’t typically traded across borders. Even among physical goods that are more likely to be imported, a big part of the final price tag is tied to domestically-produced services—that is, the retail, wholesale, and transportation services that get products from manufacturing floors to shelves. These are all expenses that won’t be directly impacted by currency fluctuations.

Food is a great example. In 2021, Canadian households consumed $105 billion worth of food, $22 billion of which was imported. Some of these items are more sensitive to currency shifts than others. For instance, 81% of fresh fruits, nuts and vegetables are shipped from other countries—and prices for these items tend to move more quickly than for others. But a significant chunk of food spending (roughly a third of the total $105 billion per year) can be traced back to value added from services. And much of that comes back to employee wages, where exchange rate volatility would have much less impact.

Canada-U.S. trade still dominates, but other markets are growing

Of course, exchange rates still matter for the share of domestic consumption that does come from abroad. But as the share of imports from non-U.S. countries and regions has grown, the greenback has become less critical than it once was. Even the value of items sourced directly from the U.S. includes a significant share of intermediate inputs sourced from other countries. According to the OECD, the U.S. accounted for roughly 46% of total Canadian consumption imports in 2018, down from 56% in 1995. Most of that decline looks to have been soaked up by China, which accounted for 12% of total consumption imports in 2018 compared to just 2% in 1995.

This matters, particularly since the Canadian dollar has appreciated relative to the Chinese yuan and Japanese yen since the end of 2021. And cheaper imports from other large trading partners like China should have at least partially offset some of the pressure brought on by a stronger greenback.

Ultimately, it’s demand that’ll sway domestic inflation

What if the Canadian dollar slumped against most other currencies? That would, by definition, be inflationary. But even then, the impacts aren’t as dramatic as often thought. Back in 2015, the Bank of Canada estimated a one-time permanent 10% broad-based depreciation in the Canadian dollar would raise headline CPI by ~0.3% in the short run (mostly on higher food and gasoline prices). And if anything, sensitivity has declined since then.

Ultimately, with so much domestic spending taken up by services, it truly will be demand for these services that makes or breaks inflation trends. And in this arena, we continue to see positive signs. In the latest Bank of Canada survey on consumer expectations (for Q1 2023), more consumers reported lower spending, particularly on discretionary services, as higher prices and borrowing costs increasingly squeezed their wallets. If that holds, we expect improvements in domestic price pressures, regardless of where the Canadian dollar might end up.

Nathan Janzen is an Assistant Chief Economist, leading the macroeconomic analysis group. His focus is on analysis and forecasting macroeconomic developments in Canada and the United States. Nathan has been with RBC since 2008 with a focus on covering the macroeconomic outlook for Canada and the United States. He has a MA in economics from McMaster University and a BA in economics from the University of Regina.

Claire Fan joined RBC as an economist since 2019 after graduating with a bachelor of business administration from the University of Toronto, and a master in financial economics from Western University. At RBC, she focuses on covering the macroeconomic outlook for Canada and the United States, and is responsible for projecting key indicators including GDP, employment and inflation. Her publications include the inflation watch series and various other analyses on labour market trends, recession probabilities and inequalities.

Proof Point is edited by Edited by Naomi Powell, Managing Editor of RBC Economics & Thought Leadership.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates. This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward- looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social- impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.